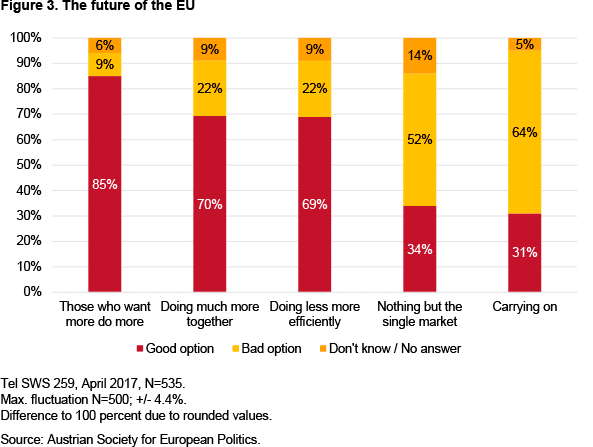

As usual, the devil is in the detail. The two coalition partners so far agree on a better implementation of the European principle of subsidiarity and support reform scenario four of the European Commission’s ‘Doing less more efficiently’.

The five options for Austria

So far, both parties want to see a rearrangement of the Union’s core competences, with a particular focus on returning power to the member states and a preference for downsizing the EU’s bureaucratic structures. They could both agree on a common criticism of EU-relocation quotas for refugees, favouring instead a deepening of cooperation in defence and security issues while promoting a tougher external border management and off-site refugee detention centres. Migration and integration will clearly remain at the centre of government action, where access to social benefits —also for EU-citizens— will be under pressure. ‘Our money for our people’ could become one of the unuttered mission statements and they could continue to show similarities with the strategic inclination of the British government. The new government will strongly argue against filling the financial gap in the future EU budget caused by the UK’s departure from the Union. A further deepening of the Euro area will be cautiously welcomed unless major elements of national sovereignty are affected and a transfer union is established without clear-cut binding rules and mutual benefits. One of the main differences with the previous government will likely be the lack of support for a social dimension of EU integration, although issues of salary dumping as well as unfair cross-border competition in Central Europe will remain on the agenda and it will be clearly in Austria’s interest to have them solved.

Austria will continue to push for ending accession negotiations with Turkey. When it comes to Russia, the government will probably favour a softer stance —still in line with international law and its EU commitments— involving more dialogue with Moscow and working towards easing and even ending the sanctions imposed. At the end of 2016 it was the FPÖ that signed a cooperation agreement with United Russia, the party of Russian President Vladimir Putin.11 A non-NATO country with a history of neutrality, Austria typically tends to occupy a low-profile role within the transatlantic relationship but is active in international organisations.

Still, the tentative new Chancellor has made it known that he wants to play a vigorous role in the debate on the future of the EU, which needs to be defined at the beginning of 2018. To achieve this object he will also need to pressure his coalition partner FPÖ to draw back from some of its ideas, such as breaking up the Union and fantasising about Austria joining the EU’s sceptical —although heterogenous— Visegrad group, which currently comprises Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.12

This is of special importance as Austria will take over the rotating EU-Council Presidency in the second half of 2018. The Austrian Presidency agenda is to focus on, among other issues, the future of a safer and more secure Europe, the refugee and migration challenge, the finalisation of the Brexit negotiations, the first proposals for the next EU budget, the evaluation of the principle of subsidiarity and the promotion of the EU perspective of the Western Balkans.

Conclusions

Austria will indeed be well advised to energetically take part in the reshaping of Europe. Instead of teaming up with Warsaw and Budapest, Vienna should rather be inspired by Berlin and Paris. It is going to promote the topics on which it can indisputably add value to the European integration process, such as the fight against youth unemployment, building bridges between the Western and Eastern European countries as well as the candidate countries of the Western Balkans, its ambitions to promote renewable instead of nuclear energy and its ideas regarding social welfare and economic growth.

At the end of the day, the new government is to be judged by its actions. An open and pro-European Austria is in the interest not only of the EU but the country itself will be the one to benefit the most.

Paul Schmidt

Secretary General of the Austrian Society for European Politics | @_PaulSchmidt

1 In 1994 other referendums on EU membership were held in Finland, Sweden and Norway and showed considerably less support for joining the Union (Finland 56.9%, Sweden 52.3% and Norway 47.8%).

2 The measures were imposed on 4 February 2000 due to fears that a government with the participation of the FPÖ could breach fundamental principles of EU law and values. The governments of the 14 member states would neither promote nor accept any official bilateral contacts at the political level with an Austrian government that included the FPÖ, no support was given to Austrian candidates seeking positions in international organisations and Austrian ambassadors in EU capitals would only be received at a technical level. These measures –commonly referred to as ‘EU sanctions’ on Austria– were widely regarded as unjustified by Austrian public opinion and were lifted on 12 September 2000.

3 ÖGfE-Umfrage: Frauen sehen die EU heute deutlich positiver als Männer, Austrian Society for European Politics.

4 ÖGfE-Umfrage: ÖsterreicherInnen wünschen sich eine flexible und effizientere Europäische Union, Austrian Society for European Politics.

5 ÖGfE-Umfrage: 15 Jahre Euro-Bargeld – ÖsterreicherInnen sehen Euro-Zukunft durchaus optimistisch, Austrian Society for European Politics.

6 See also Why Central Europe needs a unified strategy for tackling the migration crisis, LSE EUROPP.

7 ÖGfE-Umfrage: Steigende Zustimmung zur EU-Mitgliedschaft, aber Skepsis gegenüber vertiefter Euro-Zone, Austrian Society for European Politics.

8 TheLiberals (NEOS) came fourth, with 5,3% of the vote. The Liste Peter Pilz, which split from the Green Party (Die Grünen) during the election campaign, gained 4.4% and passed the threshold of the necessary 4% to enter the Nationalrat, while for Austria’s Greens the recent election was a tremendous defeat. With only 3.8% of the vote, they were excluded from Parliament, after having maiintainmed a parliamentary presence since 1986.

9 See also Is EU free movement a curse or a blessing? The case of Austria, Paul Schmidt, LSE EUROPP.

10 Nationalrat stimmt einhellig für kleines Demokratiepaket.

11 Austria’s far-right seals pact with Russia, Anthony Mills, EU Observer.

12 See also Could Austria join the Visegrád Group?, Paul Schmidt, LSE EUROPP.

Source link : https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/austria-in-europe-dynamic-perceptions-and-ambiguous-politics/

Author :

Publish date : 2017-12-11 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.