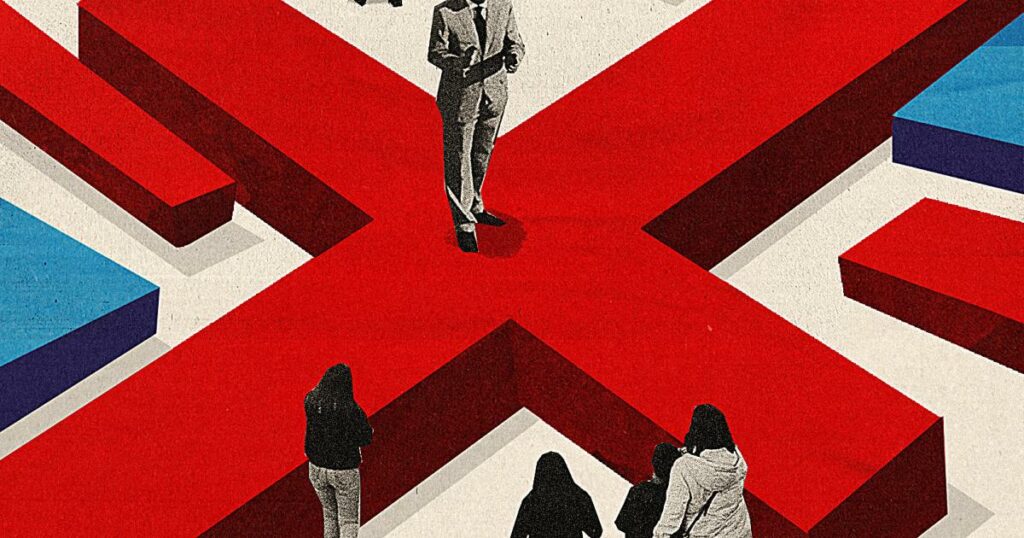

A Brexit supporter in London, January 2020

Simon Dawson / Reuters

There is, however, a further irony in the effects of Brexit on national identities within the United Kingdom. In another play that Shakespeare wrote for James I, Macbeth, the porter jokes about the effects of alcohol on “lechery”: “it provokes the desire, but it takes away the performance.” Brexit has greatly enhanced the desire for independence among the United Kingdom’s constituent parts, especially Scotland. But it makes the performance a lot more difficult. Before Brexit, political, economic, and trade relations between England and an independent Scotland would have been eased by the continuity of shared participation in Brussels’s structures and processes. Now, were England to remain outside the EU and Scotland to rejoin it, the barriers between the two nations would be formidable. Brexit may have inclined the Scots more toward independence, but it has also provided a rather scary example of how hard it is to leave a union, whether European or British. And whereas the United Kingdom was in the EU for less than 50 years, Scotland has been in the United Kingdom for more than three centuries.

Even the mechanics of holding another vote on independence are fraught. In November 2022, the British supreme court unanimously ruled that “the Scottish Parliament does not have the power to legislate for a referendum on Scottish independence.” This means that no such plebiscite can be lawful unless the British government in London agrees to it. Sturgeon is too canny to press ahead in these circumstances, her natural wariness no doubt reinforced by the bitter experience of the Catalan government, which in 2017 staged an unconstitutional and ultimately abortive referendum on independence from Spain. Her response to the ruling has been to declare that Scotland’s vote in the next British general election will be a “de facto” independence referendum. But this approach, too, is rife with uncertainties: a general election is not a referendum, and if pro-independence parties win a majority, it would still not be clear how their aims could be put into effect without London’s consent.

Nor is a serious push for a united Ireland likely to take place soon. There may no longer be a unionist majority in Northern Ireland, but there is no nationalist majority either. The most notable political trend is the large number of Northern Irish voters who say they are open-minded about the future but in no hurry to leave the United Kingdom. Over the long term, the prosperity of Ireland, the dynamic effects of Northern Ireland’s alignment with the EU, and its changing demography will make Irish unity increasingly likely—but not in the next decade.

REFORM OR DIE

What all of this means is that there may yet be a chance for the United Kingdom to save itself. Everything will depend on who forms the next British government—the next general election must take place no later than January 2025—and what that government does about constitutional reform. The current prime minister, Rishi Sunak, is a technocrat at heart and seems to have little interest in identity politics. Yet if the economic reality continues to look grim, his party may have little option but to double down on the defense of an archaic Britishness. An intransigent Conservative party that somehow wins reelection by appealing to English voters to stand firm against the rebellious Scots and rally around the existing political order could turn a slow process of dissolution into an immediate crisis. It is not hard to imagine that, amid a deepening economic recession and with Sturgeon already a hate figure for the Tory press in England (in December 2022, one column in Rupert Murdoch’s tabloid The Sun compared her to the mass murderer Rosemary West), some Conservatives might actually relish a “patriotic” rhetorical war against Scottish and Welsh nationalists. The result, however, would be merely to exacerbate divisions and speed up the end of the United Kingdom.

The current likelihood, however, is that Labour leader Keir Starmer will be the next prime minister. Starmer has endorsed a plan, drawn up by a commission headed by former Prime Minister (and proud Scot) Gordon Brown, to clean up the British Parliament, replace the unelected House of Lords with an elected second chamber of “nations and regions,” and devolve more power to local governments in what Brown calls “the biggest transfer of power out of Westminster . . . that our country has seen.” If Starmer does achieve power, he may not be quite so enthusiastic about giving it away. And even these reforms may not be enough to save the United Kingdom. The case for the creation of a fully federal state seems strong. It has worked well for the former British dominions of Canada and Australia. If Quebec, which came very close to voting for independence in 1995, has settled down as a distinct society within a larger union, might not the same be possible for Scotland and Wales? But the English habit of muddling through—what Winston Churchill called KBO, for “keep buggering on”—is a powerful force for inertia.

The United Kingdom created a beta version of democracy in the eighteenth century: innovative and progressive in its day but long since surpassed by newer models. The country has, however, been extremely reluctant to abandon even the most egregious anachronisms. The biggest transformation in its governance was joining the European Union, and that has been reversed. It now has to make a momentous and existential choice—between a radically reimagined United Kingdom and a stubborn adherence to KBO. If it chooses the latter, it will muddle on toward its own extinction.

Loading…

Source link : https://www.foreignaffairs.com/europe/disunited-kingdom-nationalism-break-britain-fintan-otoole

Author :

Publish date : 2023-02-21 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.