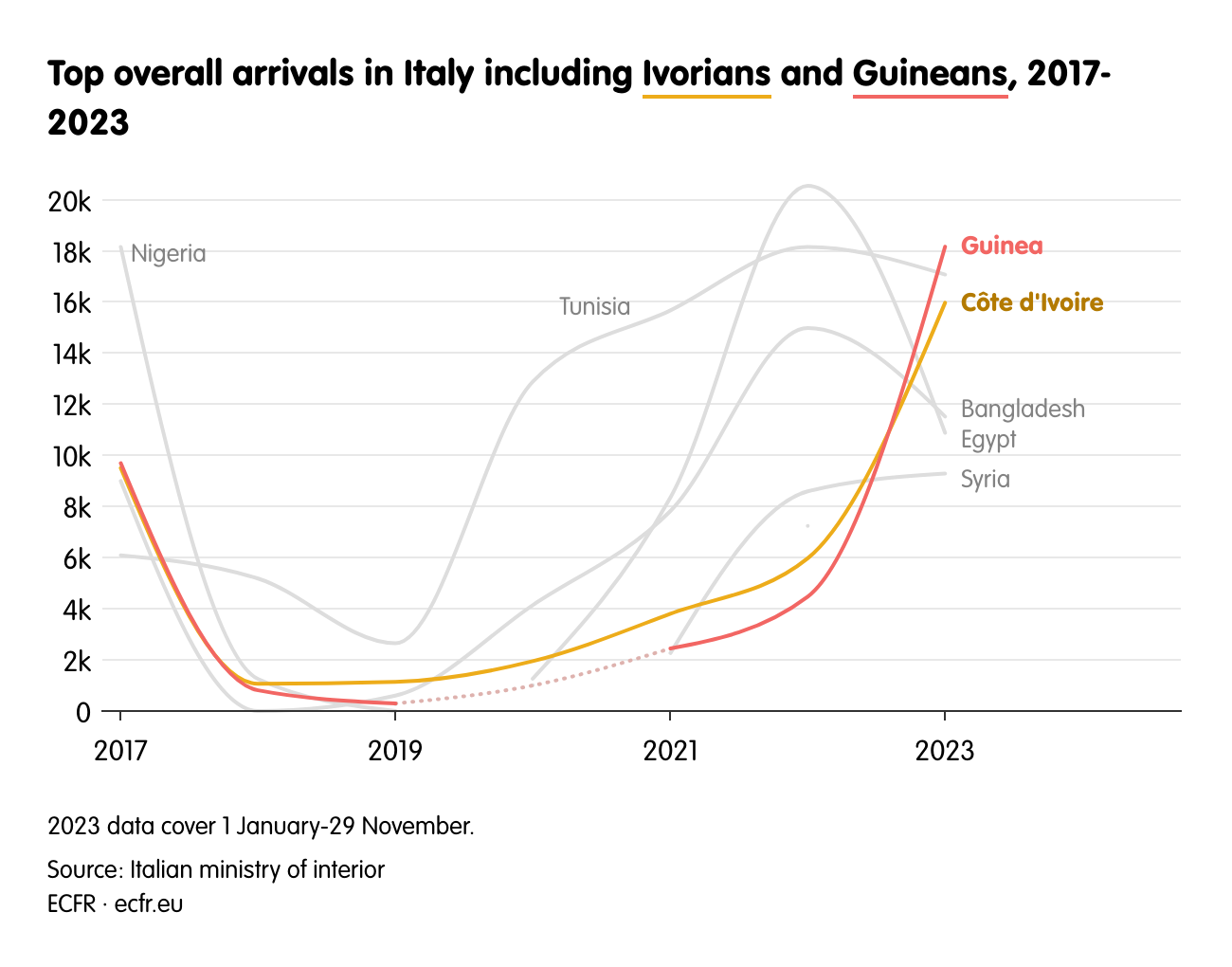

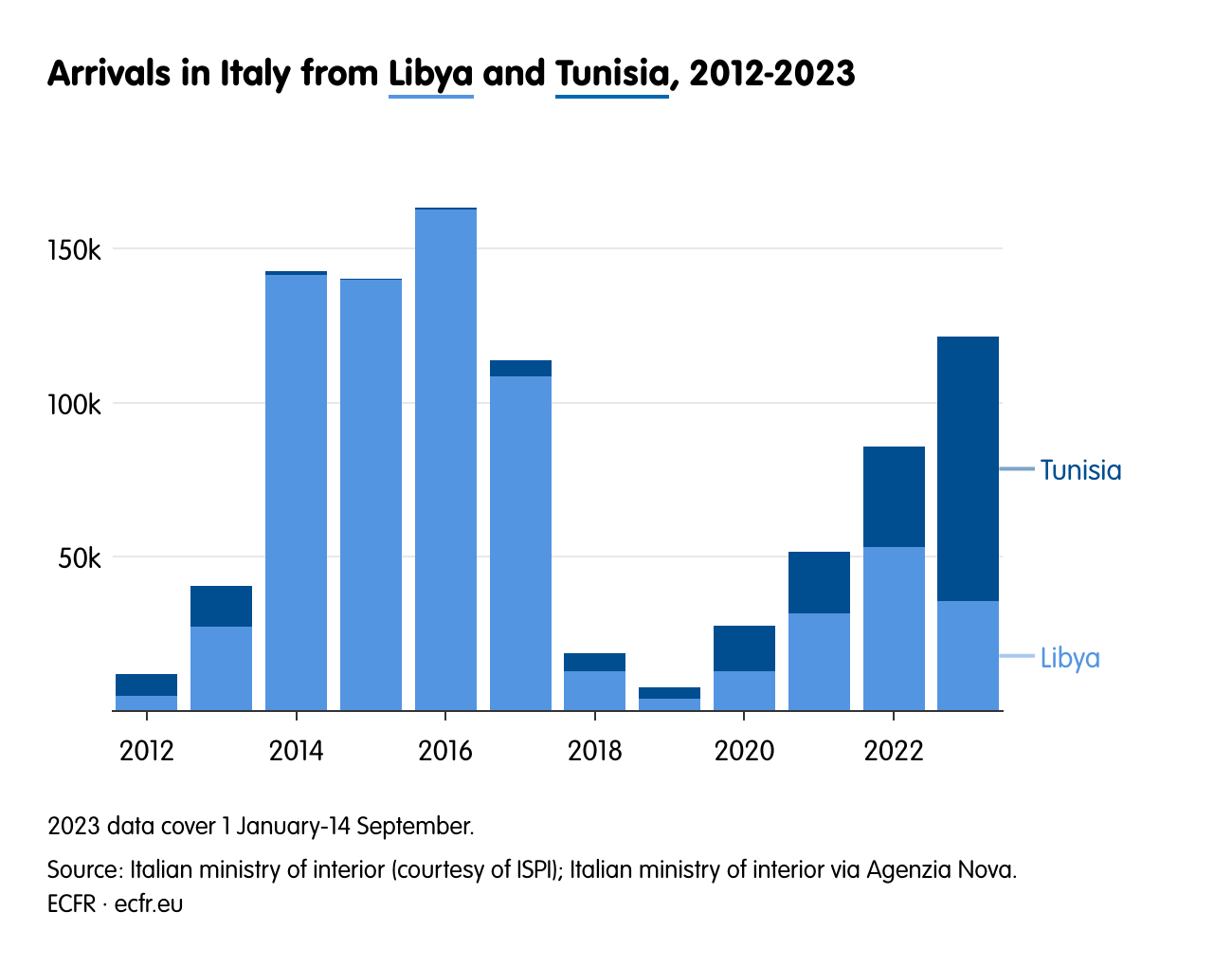

The covid-19 pandemic had a disastrous economic impact on Tunisia. But Tunisians had already been primed to migrate by years of deteriorating political and economic conditions in the country. Indeed, the numbers of Tunisians migrating to escape the social impact of those conditions had been steadily growing for some time. One 2022 survey from the Arab Barometer at Princeton University found that the percentage of Tunisians considering migration more than doubled between 2011-2022. As a result, Tunisians made up the largest group of arrivals in Italy between 2019 to 2021. Even in 2022, Italian ministry of interior data show that they remained at 17 per cent, having been displaced at the top by Egyptians arriving in Europe from eastern Libya (20.5 per cent of all arrivals).

From the second half of 2022 onwards, however, sub-Saharan Africans have become the largest group migrating to Europe from Tunisia. Europeans’ focus on Tunisia’s coast and confidence in deals with Libya meant they overlooked Tunisia’s porous land borders. As Libya descended into conflict in 2019, sub-Saharan migrants started fleeing over those borders into Tunisia. Alongside this, the covid-19 pandemic pushed many sub-Saharan migrants already in Tunisia out of their informal jobs. From 2020 onwards, a tent city began to sprawl around the offices of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) in an upmarket suburb of Tunis, comprising sub-Saharan migrants desperate for assistance and support. They largely received nothing.

But the failure of European externalisation policies to either accommodate future threats such as spillover from Libya, or to achieve their goal of managing Tunisian migration, did not stop the European Commission and Italy doubling down with a further €160m between them to continue developing Tunisia’s coastguard and counter-smuggling capabilities.

The growth in departures continued unabated. The earlier demand from Tunisians to migrate had sparked a booming migration economy.[2] This covered multiple industries from boat-building to temporary accommodation. At the start of 2023, Tunisia’s authoritarian president Kais Saied gave a speech (laden with ‘great replacement’ conspiracising beloved by the European far right) that sparked a surge in violent racism towards sub-Saharan Africans who were working or studying in the country. These migrants began to seek refuge in Europe – facilitated by the Tunisian migration economy. In the first nine months of 2023, Ivorians and Guineans represented the largest number of arrivals in Italy from Tunisia. The Ivorian community perhaps provides the clearest example: it is the largest sub-Saharan migrant community in Tunisia. But, over the first 11 months of 2023, Ivorians were among the top overall arrivals in Italy.

Despite Tunisia’s security issues for black Africans, the country likely also offers a more hospitable and safer route than Libya for migrants fleeing war and instability in countries such as Sudan, Chad, and Eritrea. And, over 2023, an estimated 5,000 people have crossed Tunisia’s land borders with Libya and Algeria.[3] Tunisian migration and the rise in transiting migrants through Tunisia have thus transformed central Mediterranean migration. In 2017, Libya was the source of 91 per cent of arrivals in Italy; in the first nine months of 2023, Italian ministry of interior data indicate that around 70 per cent departed from Tunisia and 30 per cent from Libya.

The new Tunisian route also likely represents a more fertile business environment for people smugglers than Libya, which is dominated by select militias that more often engage in trafficking.

Smuggling dynamics in the central Mediterranean

People smuggling and human trafficking are two distinct activities. The former refers to a paid service to move people across borders; the latter is an act of violent coercion based on control over those being trafficked for the purpose of exploitation. In the central Mediterranean, migrant experiences often exist on a fluctuating spectrum of smuggling and trafficking. The well-documented experience of migrants in Libya typifies this: people pay for smuggling services only to end up being ransomed, sexually abused, tortured, and forced to work to buy their freedom.

Politicians tend to reduce people smuggling and trafficking to the work of organised transnational cartels. But central Mediterranean smuggling is more a network of highly localised ‘service providers’. Migrants must therefore negotiate with different providers across each leg of their journey. These complex and fluid networks have proven highly adaptable to emergent threats from reinforced border policing, internationally supported anti-smuggling campaigns, and even global events such as the covid-19 pandemic. That is because smugglers and smuggling networks are most sensitive to economic stimuli: as long as there is demand for their services and money to pay for it, they will exist in some form or another.

Numerous services are available to migrants at different price points, depending on the length of the journey, the quality of the experience, and of course the reliability. The market is so sophisticated that people are even able to purchase crossings in bulk (as any boat could sink or be intercepted). Some offer escrow systems through “Hawala” partners to ensure that the smugglers do not receive their payment until the migrant has successfully landed in Europe. The price of the sea journey also depends on the weather: summer journeys over calm waters are considerably more expensive than winter journeys across choppy seas. North African and Asian migrants can generally afford less perilous services than those from sub-Saharan Africa.

Different countries also have very different markets. Tunisia’s smuggling networks are smaller and less developed than those of Libya. In Tunisia, a marketplace of agents offers increasingly professional packages to migrants. Sub-Saharan African agents play an increasingly prominent role in this market due to Tunisia’s transformation from an origin to a transit country – underlining the fluidity of the networks.[4] Nevertheless, sub-Saharan Africans still often travel in poor conditions and are subject to structured smuggling operations (verging upon trafficking), which carry them to the coastal towns of Zarzis and Sfax and across to Europe.

Since roughly 2021, Tunisian migrants appear to have turned away from smugglers and are instead increasingly self-smuggling. This leads to highly decentralised and irregular departures all along the coastline, resulting in sporadic waves of Tunisians arriving on Italian shores and in Tunisian morgues. Smugglers also usually have relationships with local authorities – so the shift to self-smuggling is making migratory dynamics more difficult to read and manage.

In Libya, people smugglers have undergone waves of mafia-isation as local militias become accepted actors involved in both smuggling and policing. Smuggling networks grew freely in the chaos of post-revolutionary Libya. Militias in north-western coastal cities such as Zawiya, Sabratha, and Zuwara link up with smugglers further inland, all the way down to Libya’s expansive land borders. This cooperation resulted from local militias seeking to maximise the profitability of the turf they controlled – which was smuggling for those on the northern coasts, the southern borders, and key junctions in between.

The Minniti deal that transformed these people smugglers into counter-smuggling officers represented a powerful injection of capital and opportunity. And the EU bolstered the smugglers’ financial inducements to ‘change sides’ through funding for migration projects. This became so valuable that it fed conflicts for control over migrant infrastructure in key coastal cities.

The ‘ex-smugglers’ then gravitated towards trafficking through their control of the migration-management infrastructure and the commercialisation of counter-smuggling. The groups engaged in a dark trade of migrants to detention centres: enslaving them and violently coercing money from migrants’ families to pay the fees for the crossings they still managed. Most migrants enter Libya through a smuggling system, but they almost inevitably become part of these trafficking networks. By 2019, roughly 1 per cent of Libya’s estimated 700,000 migrants were trapped in the country’s detention system. These networks have dominated in western Libya since 2016, with smaller-scale smugglers operating on the fringes.

Since 2021, Haftar in eastern Libya has sought to emulate this model. The Pylos shipwreck in June 2023, when hundreds of migrants perished in a grossly overburdened vessel, underlines how people using Haftar’s services are abused to such an extent that they can be considered trafficked, despite paying for the crossing. Like in western Libya, the violent monopolisation of the eastern market created significantly worse conditions for migrants. It also saw the removal of the higher quality and safer smuggling options available in more competitive networks.

The migrants who don’t make it

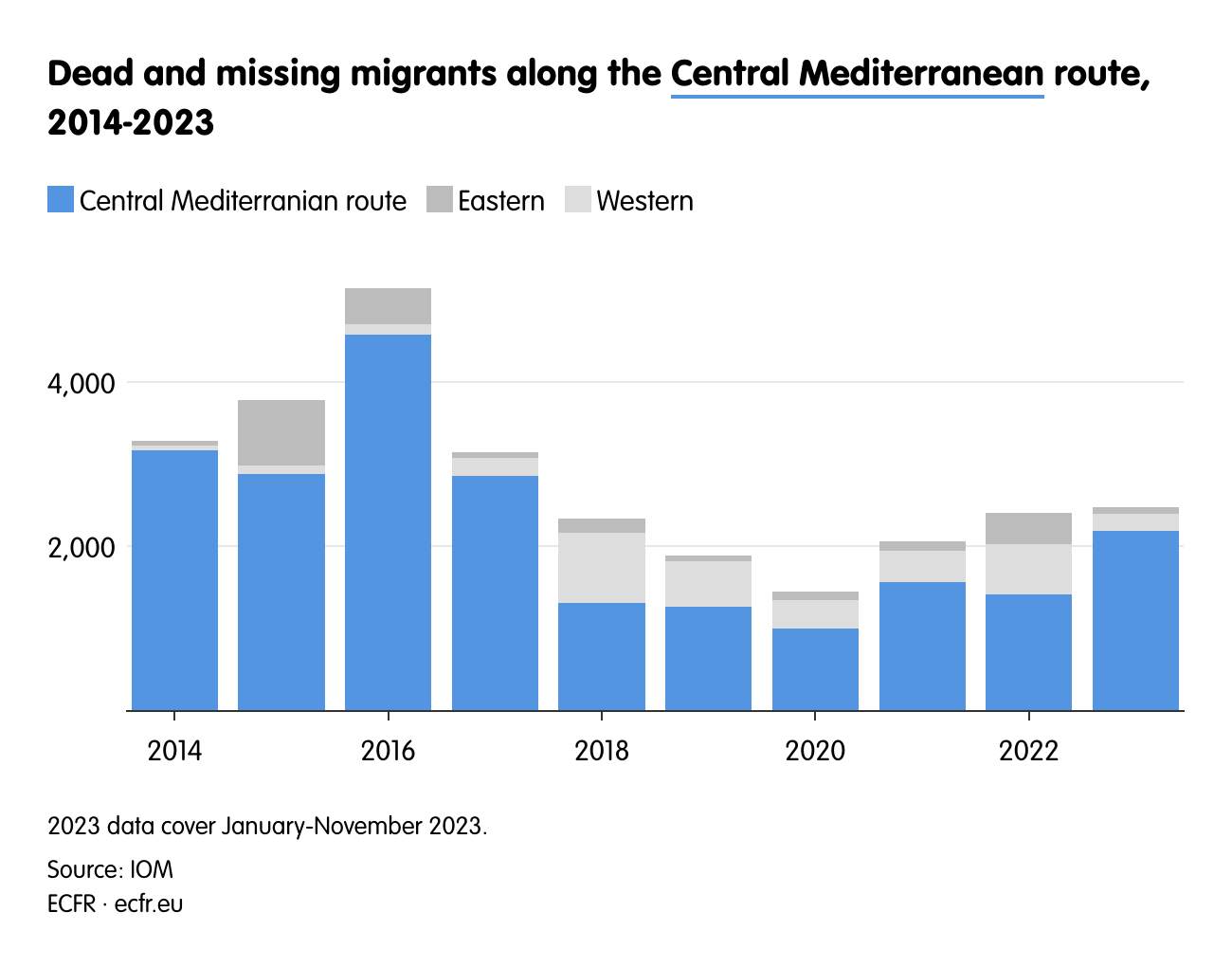

The central Mediterranean is dubbed the “the world’s deadliest migratory route”. Between January 2014 to June 2023, the route claimed more than 22,000 of a total 28,000 migrant deaths and disappearances in the entire Mediterranean. Disturbingly, the numbers could easily be far higher, as migration organisations recognise that they have no means of accurately accounting for all the “ghost ships” that leave North Africa never to arrive.

The Libya-Italy trip is particularly dangerous due to its length, especially – as the Pylos tragedy illustrated – for those travelling from eastern Libya. The trip is shorter from Tunisia, but the IOM’s Flavio Di Giacomo has called the locally-produced makeshift boats “the most fragile we have ever seen in the Mediterranean”. To make matters worse, climate change is contributing to increasingly extreme weather, further imperilling migrants at sea.

So, the increase in departures since 2020 corresponds with an increase in deaths and disappearances on the central Mediterranean route. The first nine months of 2023 recorded 2,000 fatalities – the deadliest year since 2017. Externalisation deals may have contributed to an initial drop in arrivals, but they also seem to have increased the proportion of those dying en route relative to those arriving.

Combine these numbers with those being intercepted or detained, and it suggests that – rather than stopping people migrating – externalisation deals just make the journey more arduous and dangerous, without that serving as a deterrent.

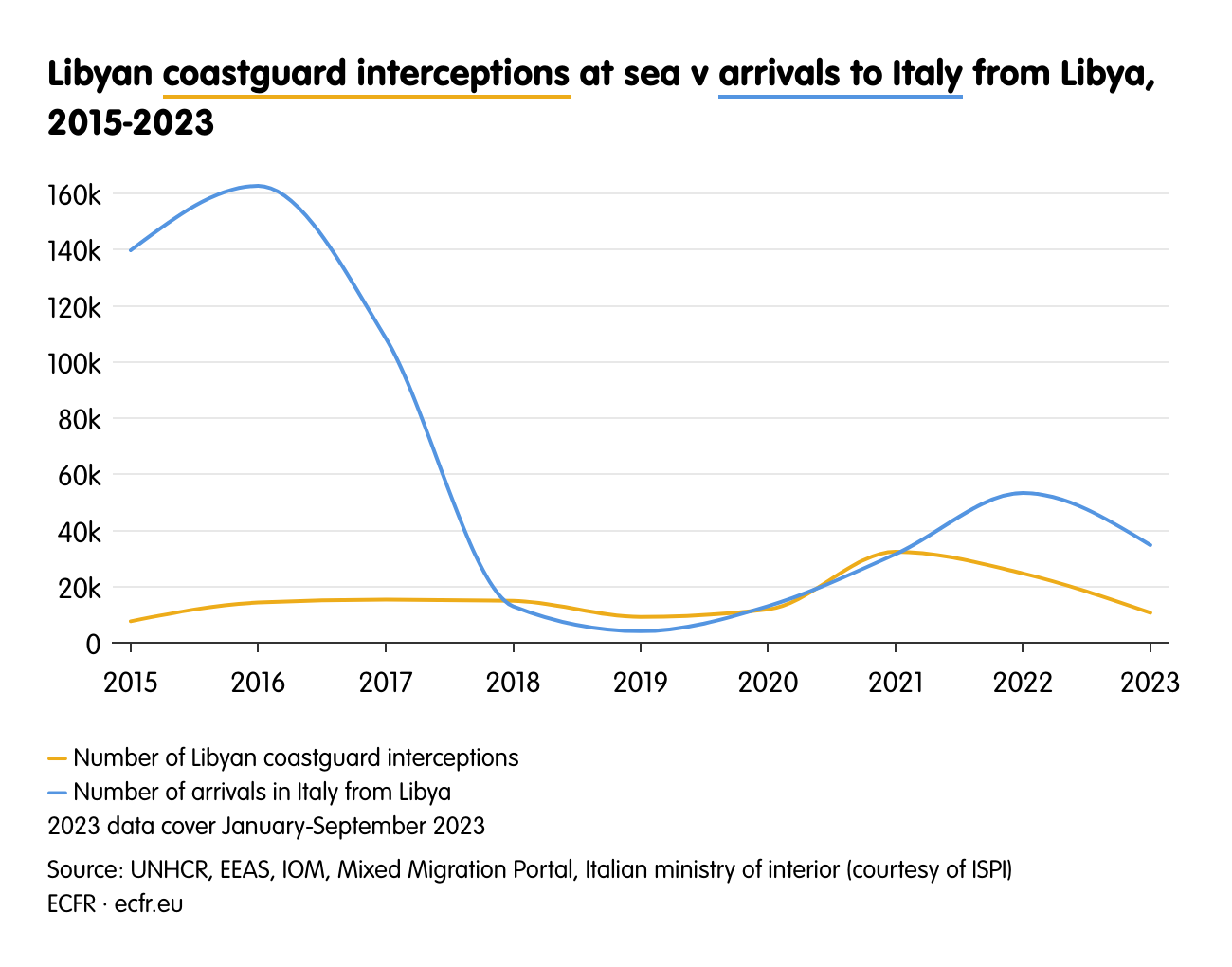

In Libya, the EU and member states have only increased their cooperation with and support for the coastguard, despite repeated instances of alarming violence against migrants at sea by the erstwhile smugglers. European border officials even help Libya’s coastguard intercept ships beyond Libyan waters. Yet, despite considerable European financial and logistical assistance, the proportion of interceptions versus arrivals suggests the coastguard is limited in its effectiveness. Coastguards cannot prevent people attempting to migrate so are most effective when the flows to Libya’s coastlines are lower.

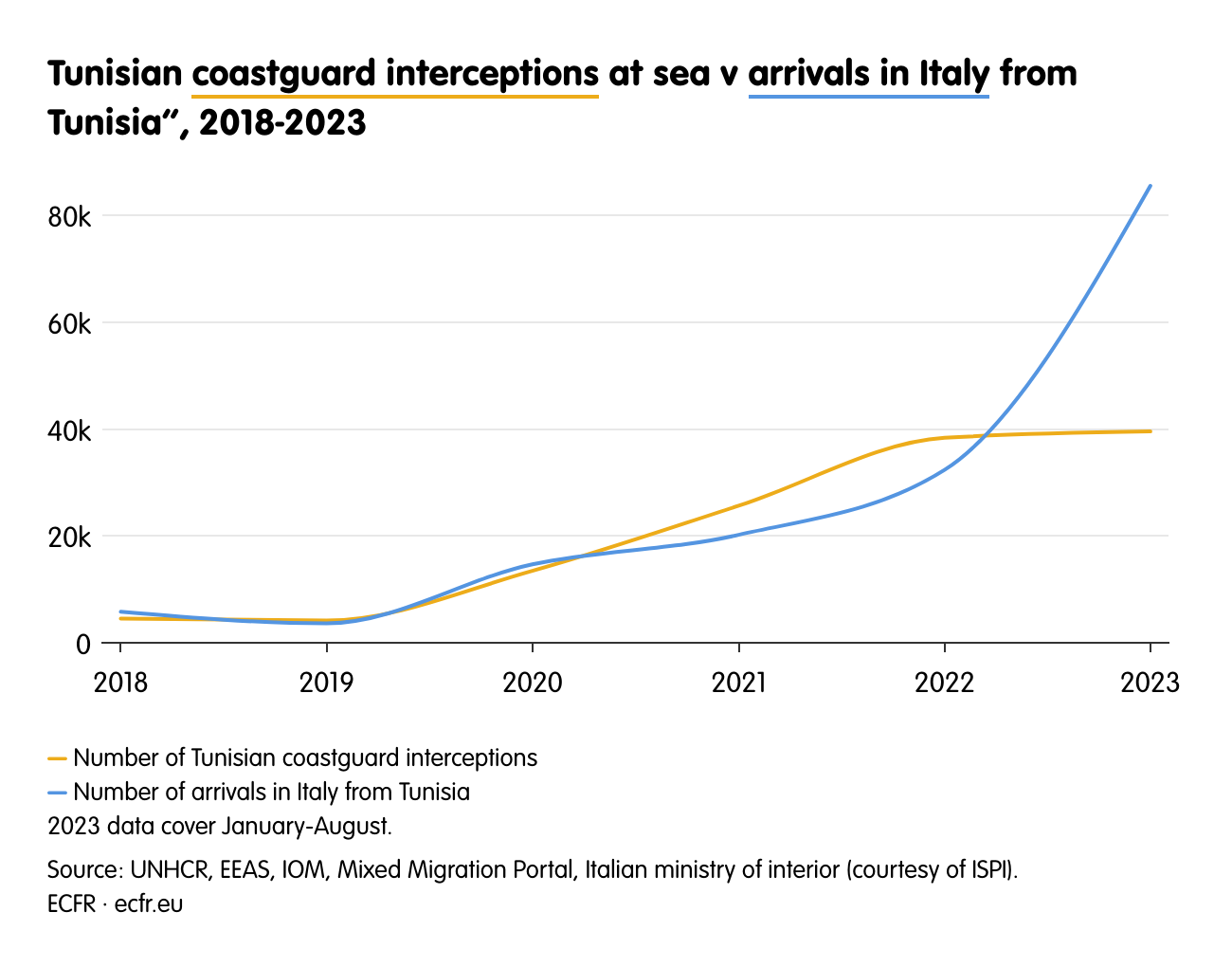

In Tunisia, steadily increasing EU and Italian support for the coastguard since 2019 resulted in a steadily increasing number of interceptions. But, as in Libya, it has failed to keep up with increasing numbers attempting to migrate and the sharp rise in departures over 2023. This again demonstrates that coastguard interceptions can inhibit arrivals but not prevent them altogether or diminish migrants’ aspirations to travel. There appears to be a certain point at which the effectiveness of coastguard interceptions plateaus.

The limitations of externalisation are thus increasingly apparent. Not only are people smugglers and traffickers highly adaptive – able to latch on to state structures to either dominate them, co-opt them, or dovetail with them – but they are also highly responsive to changing political and economic conditions. The scale of demand is what drives these hydra-esque qualities of the illicit migration industry, creating a migratory phenomenon that is too vast for border forces to effectively contain or curtail beyond a certain limit. The most notable impact of European securitisation and externalisation policies is therefore not to curtail migration or neutralise smugglers and traffickers, but to increase the value of the smugglers’ services and imperil the lives of those who use them.

Europeans should not expect this demand for migration and smuggling simply to disappear. The political volatility around Africa’s “coup belt”, for example, is degrading previously poor and poorly-functioning state systems across the Sahel and west Africa: regions that already supply significant numbers of migrants to the central Mediterranean route. The ongoing civil war in Sudan is also creating a migratory wave. In its first five months, that war resulted in 5 million forcibly displaced people, of whom an estimated 1 million have already travelled abroad – fast outstripping UN estimates of 815,000 refugees. Sudanese refugees are already travelling through Libya and Tunisia towards Europe; this will likely intensify as the conflict continues.

Moreover, many of the world’s most climate vulnerable locations are across the Middle East and Africa. Climate-related migration is already beginning in North Africa, for instance, where Tunisia faces a severe drought that is decimating agriculture in an environment of already prevalent food insecurity. In Libya, an entire city was destroyed by a recent hurricane. That catastrophe created a wave of tens of thousands of internally displaced people, also highlighting the inability of the region’s kleptocracies to manage natural disasters that are becoming more frequent. Further east, countries such as Pakistan and Bangladesh are highly climate vulnerable too – and already have a high rate of migration to Europe. Climate change’s steadily worsening consequences will exacerbate failing states and struggling economies across the Middle East and Africa, as well as drive conflicts over increasingly scarce resources.

Another concerning multiplier is that while historically most African migration takes place within the continent, the increasing prevalence of conflicts and sudden hostility of previous migratory focal points in North Africa like Tunisia will push more people towards Europe. Externalisation cannot address underlying migratory drivers such as these. In fact, it may exacerbate them.

The price of not securing the moat

A focus on arrival numbers not only blurs the picture of what is happening on the central Mediterranean route, it also obscures the consequences of externalisation for Europe’s partner countries. That is, externalisation hinders the long-term development of Libya and Tunisia – thereby also making them more susceptible to smugglers and migration – and undermines a diverse set of European geopolitical interests in the southern Mediterranean and beyond.

Libya

The Minniti deal came at a significant cost – both for Libya and for Europe. Libya’s government was already weak; Italy weakened it further by directly negotiating with militias. The deal provided non-state groups with an independent means of empowerment and further leverage over the government in Tripoli. The militias’ new role as migration enforcers may have been less financially profitable than smuggling, but it gave them the security of being formally under Libya’s interior ministry. This in turn gave them access to government funding for salaries and profitable public-sector corruption mechanisms. By making migrants victims of trafficking, the Minniti deal also increased the likelihood that they would be forced into Europe’s illicit economies following the journey.

Embarrassingly, two major beneficiaries of the Minniti deal, Mohammed Kashlaf, who managed a notorious detention centre in Zawiya, and Abdel-Rahman Milad (Al-Bidja), who headed Zawiya’s coastguard unit, were placed under UN sanctions in 2018 for trafficking. In a demonstration of how non-state groups had accumulated significant power over any Libyan civilian government, they escaped any real punishment. In September 2021, Libya’s prime minister appointed Milad to a prestigious role as the head of Libya’s naval academy.

So, instead of trying to develop a long-term partner in the Libyan government, Italian leaders snatched a short-term success. They may now be coming to rue that decision as the Haftars are sending migrants across the Mediterranean in large numbers in a bid to get the same deal. Haftar aims to use migration as leverage to develop a working partnership with Italy and the EU. That partnership would help to empower him politically, militarily, and financially – against the current European consensus on Libya of recognising the government in Tripoli and pushing for elections.

By training and funding Libya’s counter-migration apparatus, the EU also tied itself to these unsavoury actors at great reputational cost for a values-based power. This likely does little to nullify accusations of hypocrisy from leaders in the global south when Europeans come calling to shore up the rules-based international order. Indeed, human rights groups argue that the EU’s and member states’ externalisation policy in Libya is a strategy to shirk their legal responsibilities by keeping migrants in Libya where they are subject to extreme abuse by the militias-turned-coastguards.

Despite the coastguard’s abuses, EU border agency Frontex allegedly helps it capture migrant ships in a likely violation of the principle of non-refoulement. One recent investigation found that Maltese authorities and Frontex have taken this a step further by employing Haftar’s brigade to pull migrant vessels back from Maltese waters to eastern Libya; simultaneously pulling Europeans into even dirtier legal waters in their quest to externalise borders.

In March 2023, a UN Human Rights Council (HRC) Fact Finding Mission into abuses in Libya called on the EU and member states to withdraw their support for the Libyan coastguard. The EU responded with hostile indifference. The next HRC session a saw European states including Italy and Malta help to quietly bury the mission; others simply turned a blind eye to its demise. This was a mission that the Netherlands and other member-states had spent years trying to initiate to advance accountability in Libya. And it could have proven a powerful tool in advancing Libya’s political process and security sector reform.

Moreover, at least since 2016, countries such as Italy, Greece, France, Germany, Denmark, and Spain have increasingly criminalised NGO’s attempts to rescue migrants by deploying counter-smuggling laws. This has hampered search and rescue missions, increasing the chances of a migrant dying in the waters off Libya from 1-in-42 in 2016 to 1-in-18 in 2018. The situation worsened in 2020, when the EU removed the search and rescue mandate of its naval mission in the Mediterranean, while retaining support functions to the Libyan coastguard. Member states such as Austria forced this move by threatening to block the mission’s renewal, claiming that search and rescue creates a “pull factor” for migration to Europe.[5] There is, however, no evidence to support the pull factor argument – while proof of its deadly consequences increases by the day. A sorry state of affairs that demonstrates how a commitment to externalisation policies comes at the cost of other important European interests and policy projects.

The EU’s response now that numbers of crossings are nearing the crisis years once more is eerily familiar: to double down on a securitised approach to migration hoping to strengthen border externalisation (albeit stating that more needs to be done to protect human rights). The bloc’s new action plan for the central Mediterranean focuses on strengthening Libya’s border management capacities and tightening their integration with Frontex through the EU border assistance mechanism. The EU is also rehashing diplomatic vehicles such as its trilateral Libya taskforce with the UN and the African Union, in the hopes of enhancing mechanisms for voluntary repatriations of migrants. Given that people are willing to risk their lives and freedom to arrive in Europe, any voluntary returns plan seems doomed to have limited impact.

In short, the main lesson from Libya should be that the EU traded its values, resources, and Libya stabilisation policies not for a robust externalisation partnership but for time. While Libya’s state remains weak and overrun by the interests of armed non-state actors, the Minniti deal did result in a substantial drop in arrival numbers from 2018 onwards – which dispelled the feelings of crisis around irregular migration in Europe. But that deal came at great cost and would never have stopped arrivals forever. This is because it did not target underlying migratory drivers and inadvertently strengthened smugglers and traffickers.

Tunisia

The Tunisian case underlines the cost of externalisation for the EU and member states and their values-based foreign policy. Thanks to Italy’s longstanding returns policies, Tunisians often represent around 70 per cent of deportees from the country each year. But that only accounts for just under 2,000 returns annually; a negligible number when tens of thousands of people arrive in Italy annually. Again, this is because migrants retain the rights to claim asylum, access other migrant schemes such as family reunification, and are protected from collective expulsion under article four of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Italy has tried to ameliorate this by bamboozling newly arriving Tunisian migrants into surrendering these rights through a series of administrative and legal traps, an activity recently ruled to be in violation of multiple ECHR articles.

In their desperation to make repatriation work, Italian governments have exposed themselves to legal damage. But, as the numbers show, this has been to very little avail. Italy’s problem is not that it lacks the diplomatic framework to repatriate Tunisian migrants; it is that it lacks the administrative capacity to provide Tunisian migrants (and the tens of thousands of other migrants who arrive annually) the legal process that is their right. It also lacks the capacity to actually repatriate many of those found ineligible for asylum, who often disappear into other member states and into the illicit economy.

Recent developments in Tunisia also again illustrate the risks to European interests of surrendering control of migration policy to authoritarian or weak regimes. Over 2023, as Tunisian migration waned while sub-Saharan migration grew, Meloni led a ‘team Europe’ response to forge a new migration deal with Saied. In July 2023, the parties agreed a memorandum of understanding that could have symbolised the start of a new approach to migration partnerships.

Instead of the traditional securitised framework, the deal framed European migration support for Tunisia within a broader context of sustainable development, with the aim of cutting medium to long-term migration. Only one of the deal’s five pillars explicitly relates to migration. The broader provisions included a pledge of €150m of direct budgetary support to ameliorate Tunisia’s balance of payments crisis, and a further €900m in macroeconomic support that was conditional on Tunisia agreeing a broader package of cash for reforms from the International Monetary Fund. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen trumpeted the deal as a model agreement for other southern Mediterranean countries.

The specific migration provisions of the deal, however, remained focused on externalisation. With a sense of déjà vu, the EU would immediately disburse €105m to enhance Tunisia’s border management capacities. Meloni and the EU also built up the deal and framed its announcement as a migration deal. Subsequent commentary on the matter followed suit: Italy and Tunisia had struck a new migration deal to strengthen the latter’s borders. A flurry of criticism followed, given that the deal would bolster Tunisia’s interior ministry at a time when Tunisian security services were flagrantly abusing migrants in the wake of Saied’s incendiary speech.

Saied benefited from the legitimisation of high-level visits by European leaders. The deal was announced in Tunis by Saied, the Dutch and Italian prime ministers, and von der Leyen at a press conference (with no press allowed). This sent a message that the EU was aligned with an authoritarian president who had dismantled a democracy Europeans had spent the last decade promoting – an isolating and chilling moment for democratic advocates across North Africa.

It also provided political validation and economic support for a coastguard service mired in abuse allegations, and security services that were deporting migrants (including children and pregnant women) into desert border zones and leaving them there to die. Critics of the deal argue that Europe’s political and economic support to Saied empowers him to continue pursuing a policy path that is wrecking Tunisia’s state and economy – sacrificing the leverage Europeans need to press him to change from a course that will eventually cause another huge surge in Tunisian migration.

The deal also contributed to divisions and discord within the EU. German decision-makers, for instance, insisted that the EU could provide none of the funding without Saied agreeing to the IMF bailout deal, following his disastrous management of Tunisia’s economy. Saied had recently rejected a deal his government had developed with the IMF, claiming he could not tolerate foreign dictats in reference to the deal’s austerity policies. This caused considerable consternation in Europe given Tunisia’s need for constant budget support to maintain imports of crucial goods like food and medicines.

Behind the scenes, German policymakers and others also expressed frustration that the deal had taken place under a European banner without first obtaining a European-wide agreement. For Italian policymakers and von der Leyen, on the other hand, the pact represented the formalisation of longstanding collective positions on migration: funding for the deal’s migration components was separate, ring-fenced, and therefore not conditional on Saied accepting the IMF proposal. These behind-the-scenes disputes escalated to the point that Germany’s foreign minister wrote to the European Commission claiming that insufficient consultation with member states, as well as the deal’s lack of consideration for human rights and procedural faults, meant that it could not become a template for future agreements. EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell echoed these sentiments, privately warning the EU may well lose in court if sued over the deal. The agreement sparked similar clashes in the European Parliament.

Despite this, Italy and the European Commission pressed on. Following a mini-crisis that saw 7,000 migrants arrive in Lampedusa in just two days, they supplied parts to help Tunisia’s coastguard maintain vessels, alongside €127m of further support. But this only vindicated the analysts, activists, and migration experts who had long critiqued EU migration policy as reactionary.

As discussed, coastguard interceptions are most successful when the numbers of people migrating are low – and the numbers of interceptions by Tunisia’s coastguard are plateauing while crossings are rising. This raises the question of whether Tunisia has the capacity to provide further externalisation concessions to Europe. Moreover, recent reports suggest that the coastguard is increasingly hampered by administrative issues and corruption; problems that sending money and equipment do not solve.

Saied himself has rejected the concept of externalisation, repeatedly proclaiming that Tunisia would not be Europe’s border guard; nor would it become a country of resettlement for migrants deported from Europe. He even seems to be driving out migrants who study and work within Tunisia. That he continues to engage in counter-migration negotiations could suggest other motives: he may be trying to boost the coffers of an interior ministry he increasingly relies upon to cling on to power; or he may be extorting the legitimacy Europeans provide by playing to their migratory fears. As we have seen, this is a common tactic by the region’s dictators.

Said lent credence to these more cynical readings by sending back the initial disbursement of EU funds, calling it derisory and not what was promised – and forcing Europeans back to the negotiating table. This was an unprecedented move, and one that suggests Saied thought he would receive the entire €1.1 billion pledged in the deal as migration cooperation financing (irrespective of any IMF deal). European attempts to market the agreement both as a migration deal and a broader partnership package were therefore at best confusing. The flagship deal now looks to be on the rocks, in part due to its success depending on the mercurial character of a dictator.

In Tunisia, just as in Libya, numerous migration deals over more than a decade seem to be powerless to influence the underlying currents of migration. Instead, they prove more effective at endangering migrants, degrading their rights, and shoring up the power and leverage of authoritarian leaders. This reinforces the destabilising political dynamics that create further migration.

Untangling the Gordian knot

After years of doubling down on securitisation and externalisation, Europe has become the proverbial man with a hammer: only seeing nails when the situation requires a range of economic, diplomatic, and political tools deployed cohesively by a coalition.

Securitisation led to the creation of a lucrative externalisation market. This has now trickled down to North Africa, where Tunisia and Libya criminalise and commoditise the many migrants they once absorbed. The result is more irregular arrivals in Europe.

Creating and managing externalisation partnerships has also dominated European relationships with the wider southern neighbourhood since 2014. This comes at the cost of pursuing other long-term interests. It surrenders European leverage and fuels accusations of hypocrisy that undermine efforts to develop closer political and economic partnerships. It stands in the way of stabilising long-term crisis zones such as Libya and the Sahel. And it displaces resources that could be used to promote sustainable development. Progress on all these fronts would reduce the need for people to migrate in the first place, and help repair the status of current transit countries such as Libya and Tunisia as countries of destination for migrants.

Moreover, the securitised framing divides the EU thanks to the trade-offs against European values that externalisation demands. The perception of migrants as a security risk – and migration as something to be defended against – is thus turning Europeans against each other when they most need to work together. A recent leaked call between Meloni and a prankster pretending to be an African leader highlights Italian anxiety that it is now being made a buffer zone by northern Europe, just it has tried to make a buffer zone of northern Africa.

The root of Europe’s migration conundrum is insecurity: the twin anxieties of a lack of control over migration flows and misplaced blame on migrants for socio-political problems such as crime and wage stagnation. This serves as easy pickings for a politics of fear. Yet, just as in the 1990s, European economies still need migrants to fill labour and skills shortages. But now, major European countries such as Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom also require young migrants to rebalance their ageing populations.

However, when people arrive in an uncontrolled fashion by the tens of thousands, it feeds anxieties and closes the space to promote the benefits of migration. It also makes productive assimilation almost impossible. Asylum systems become overwhelmed, leaving thousands of people stranded, unable to work, in camps or makeshift accommodation, as a burden to the state. This churns migrants into the shadow economy or unregulated work. Those who are trafficked are often pushed straight into crime or forced labour. Popular feelings of a lack of control over migrants become replicated in rhetoric at the political level.

European politicians need to show their electorates that they are “taking back control” over migration. But ironically, the externalisation policy they keep doubling down upon to assuage these anxieties necessitates relinquishing control over migration flows. By definition, externalisation hands migration management to a partner country – whose leaders often have more interest in leveraging European anxieties about migration to accrue benefits for themselves than in stopping migration.

To truly control migration and fight the crisis-extortion cycle, Europeans will have to undermine the business of people smugglers. The only way to sap the massive demand that drives this illicit business is through broadened visa programmes and upgraded asylum processing. This would provide European leaders with tangible evidence of ‘doing something’ about migration flows.

Ultimately, this would enable complete European ownership over migrant arrivals, processing, and distribution – targeting settlement to where migrants can best support European economies. With genuine control to show electorates, policymakers may then have the space to develop a more systematic policy platform to engage the developmental, governance, and policing requirements of origin and transit countries that is needed to manage migration over the longer term.

Such an approach may been political suicide just a couple of years ago. But, as the new wave of sea arrivals buffs away the sheen of externalisation policies, Europeans seem to be reassessing their options. Nowhere is this more evident than in Italy, where Meloni – who was carried into office on the back of promising extreme securitisation and externalisation – seems to be trying to manufacture new migration policies that can balance the short-term imperative with longer term migration management mechanisms.

This should be the focus the Mattei Plan, a roadmap under construction for a win-win strategic partnership with Africa: the promotion of African countries’ economic development, adaptation, and resilience to climate change would result for Italy (and Europe) into a decrease of migration flows. Moreover, Meloni included expanded Italian visa programmes with Tunisia as the carrot component of her externalisation negotiations with Saied. The July 2023 Rome conference conclusions also accentuated the need to: defend the human rights of migrants, create broadened visa programmes as a means of undercutting illicit migration, found developmental programmes as part of migration partnerships between Europe and Africa, and reframe the European approach from bilateral to collective solutions.

Multilateral conference conclusions usually struggle to make it off the page. But Europeans should still recognise this as a potentially pivotal moment: all of these arguments have been made before – but never under the roof of an Italian government that swept into power on the basis of anti-immigrant sentiment.

How to seize the opportunity

Europeans need to treat migration as the long-term, structural phenomenon that it is – not just react to crisis after crisis. This implies that they need to balance short and long-term policy moves to successfully regain control.

Internalise the flaws of externalisation

Border externalisation has so far been practically the sole vehicle towards that goal. But Europeans need to acknowledge that externalisation is an imperfect tool rather than a solution in and of itself. The EU’s and member states’ experiences in the Mediterranean show that externalisation is only of limited effectiveness in reducing arrivals. It will not be able to stop migration. It also lessens European control over migration flows, handing that power to a third state.

In some cases, externalisation can temporarily slow migration and buy Europeans the political space and time to enact more comprehensive policies. The success of externalisation is also dependent on the choice of partners, their capacity, what incentivisation tools are available, and how feasible it is to control crossings. This, in turn, depends on the size of the crossing points, the sophistication of smugglers, the demand for crossings, and the competence of local authorities.

Europeans should therefore deploy externalisation only as one context-specific tool among many. They could sometimes use it to reduce numbers in the short term and as a bridge to a deeper relationship with a suitable partner country. But any use of externalisation needs to do more than pay lip service to human rights so that it does not undermine the EU’s values-based foreign policy. That deeper relationship should therefore aim to undermine the business model of smugglers and develop a working partnership that neutralises the abuses migrants suffer at the hands of local border forces.

Reset the balance of leverage

Europeans can improve the current deployment of externalisation by developing broader agreements that include visas with partner countries in exchange for joint counter-smuggling partnerships. This would help to reverse the power shift implicit in externalisation policies. Enlarged visa programmes with origin countries would bring considerable leverage for European governments. Agreements such as these would open the door to enhanced cooperation in combatting traffickers and improving policing standards at the borders.

Europeans and their partners should apply this leverage at the popular level. Enhanced legal routes could involve measures to discourage migrants from using smugglers by ensuring that the costs of taking an irregular route outweigh the benefits; for instance, by enhancing repatriation schemes and making future access to visas more complex or slower for those who use smugglers.

More and easier visa access would be popular measure in origin countries. This would increase European soft power with local populations and their governments. Even authoritarian governments are sensitive to the street and benefit from remittances from migrants in Europe. Europeans could leverage this to facilitate more active involvement in joint counter-smuggling operations that would help to prevent the kind of human rights violations that occur when local forces capture migrants at sea or raid smuggling hotspots.

Europeans need to underpin this with fair and efficient asylum processing. The ability to process incoming claimants reduces the bad optics of thousands of refugees stranded in camps. It also allows unsuccessful claimants to be quickly returned and those who are successful to receive the care they need. Moreover, successful claimants can be rapidly integrated into becoming productive members of their new communities. Improving asylum processing measures is thus a pre-requisite to the appearance of control over migration and a stronger negotiating position with partner states.

Process the need for intra-EU solidarity

This all requires solidarity within the EU: more capably handling migration is a common European problem and requires a combined European solution to be effective. For example, the EU should increase its efforts to assist the Italian government in processing irregular arrivals. This would also help alleviate Italy of an undue burden that drives resentment and political tensions.

To be most effective, visa and counter-smuggling agreements also need to be applied cohesively by multiple European states. Italy should therefore conduct negotiations over legal visa routes in concert with other member states, especially those that need migrants. Negotiating on a joint platform allows for broader European involvement in partnerships with transit countries over cooperative border security and with origin countries over development cooperation.

Member states’ initial steps to explore mechanisms to create more accessible work, student, and other visas – and their negotiations with partner states – could then become the platform to build on this year’s discussions in the European Parliament on an intra-European migration deal. These have focused on reaching an agreement to allocate arrivals where they can be assimilated productively, and have proven fractious. Visa agreements could help to overcome some of these barriers.

Ultimately, Europeans need to work to realise the conclusions of the Rome conference. That would allow them to maximise the mutual economic benefit of migration and undermine the drivers of mass migration. They should work through multilateral vehicles like the EU and development banks to support origin countries towards sustainable development. This would also pay the geopolitical dividend of creating closer ties between Europe and these states: a true asset in an era of increased multipolarity and competition between powers.

*

For decades, European countries have framed migration as a security risk and doubled down again and again on border externalisation in response. And for decades, externalisation has resulted in increasing arrival numbers, extortion from Europe’s North African partners, complicity in human rights abuses, and the opportunity cost of other strategic interests. It bears repeating: it is time to try a different approach.

About the authors

Lorena Stella Martini worked as an assistant to the Rome office of the European Council on Foreign Relations between 2021 and 2023. Since October 2023, she has been a policy advisor for the foreign policy programme at the Italian climate change think-tank ECCO.

Tarek Megerisi is a senior policy fellow with the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He has worked with a range of stakeholders over the past ten years, assisting with state transitions following the Arab uprisings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their ECFR colleagues Arturo Varvelli and Julien Barnes Dacey for supporting this project from the start. They would also like to thank Kim Butson for her patient and meticulous editing and Nastassia Zenovich for her assistance with charts and wise suggestions on data visualisations. Finally, this brief would not have been possible without all the long conversations with interlocutors who provided us with insights on migration trends and dynamics in the Mediterranean.

[1] Authors’ interviews with European officials and practitioners involved at different stages of migration project work funded by the EU, off the record, Rome, September 2023.

[2] Authors’ conversation with expert on migration, off the record, Rome, September 2023.

[3] Authors’ conversation with expert on Tunisia and migration, off the record, Rome, September 2023.

[4] Authors’ conversation with an expert on Tunisia and migration, off the record, September 2023.

[5] Authors’ interviews with those privy to EU parliament debates, off the record, 2020.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.

Source link : https://ecfr.eu/publication/road-to-nowhere-why-europes-border-externalisation-is-a-dead-end/

Author :

Publish date : 2023-12-14 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.