Old Town Market Place, Warsaw in 1945. (via Wikimedia Commons)

By February 1945, the Allies were winning the war and Roosevelt looked to lock in victory and set to order a post-war world. As Woodrow Wilson did with his Fourteen Points near the end of World War One, Roosevelt was aiming high: he and Churchill had issued the Atlantic Charter in August 1941 that laid out post-war principles, including freedom for all nations to choose their form of government, an open trading system, freedom from external aggression, and a broader system of general security to prevent a return of great power rivalry and war.

At

Yalta, Roosevelt sought to apply these principles and thought he could bring

Stalin into his new, rules-based system. He achieved a lot: Stalin’s agreement

to enter the war against Japan three months after victory over Germany;

agreements about Germany’s occupation, including an occupation zone for France;

and Stalin’s acceptance of his signature initiative, the United Nations, which

was intended, as Wilson had intended for the League of Nations, to enforce the

post-War order. (To obtain Stalin’s agreement to the UN, however, Roosevelt

accepted a Soviet right of veto in the UN Security Council, a sweetener which

weakened the UN from the beginning.)

Roosevelt

also got Stalin’s agreement to a Declaration

of Liberated Europe, a document that sought to apply the Atlantic Charter’s

principles to the countries being liberated from Nazi occupation, especially

Poland, for whose sake the UK had declared war on Germany. A key passage read:

“This is a principle of the Atlantic Charter—the right of all people to choose the form of government under which they will live. [T]he three governments [US, UK, Soviet] will jointly assist the people in any European liberated state or former Axis state in Europe where, in their judgment conditions require…to form interim governmental authorities broadly representative of all democratic elements in the population and pledged to the earliest possible establishment through free elections of Governments responsive to the will of the people.”

But that

language met a hard reality: by February 1945, Soviet armies were in control of

most of Poland and, as Roosevelt and his team knew, Stalin was already

installing communist governments there and in other places within his control.

Whether

or not the Yalta agreements were the best Roosevelt could do for Poland at that

time, they were a bad deal. The United States accepted weak promises from a

dictator on behalf of an ally, Poland, that had fought from the first day of World

War Two to the last, on all European fronts, without surrender or national

collaboration. By extension, the United States was throwing up its hands as the

Soviet Union imposed its rule on Central and Eastern Europe.

The failure of the Declaration of Liberated Europe to provide for Poland’s and Central Europe’s liberation colors how the Yalta Conference has been regarded ever since. Roosevelt’s reputation has taken hits for Yalta.

But Yalta was not simply the failure

of one US president at one meeting. The road to Yalta was the product of the

doctrine of isolationism and the original “America First” movement that

reflected conviction by great parts of the US political left and right that the

United States had no vital interests in European security. Left and right isolationists

agreed that the United States had been tricked into World War One for no good

reason by a cabal of cynical Anglo-French politicians and arms merchants. The

default by most European powers of World War One debt to the United States

fueled the sentiment that the United States was badly treated by European

powers and that it should have nothing more to do with grand, Wilsonian

visions. Roosevelt’s foreign policy was constrained by the isolationists’

political power and, as a result, the United States left Britain and France,

weakened by World War One, to deal with Hitler and Stalin on their own.

The consequences were catastrophic. It

took the German conquest of France in June 1940 to substantially weaken the

political power of the isolationists. By then, good outcomes were unobtainable.

The United States was playing catch up from a bad position. When the United

States entered World War Two in December 1941, it needed Stalin to defeat

Hitler.

From

that point, the bad choices Roosevelt faced at Yalta were nearly baked in. The

United States might have tried to force a showdown with Stalin over Poland and

Central Europe at an earlier phase of the war. The Tehran Summit in November

1943 was one such occasion. George Kennan, the United States’ first Soviet

expert and the number two at the US Embassy in Moscow, argued that the Warsaw

Uprising, the desperate revolt against the Germans by forces of the free Polish

Government in August 1944 provided another. The United States might have presented

the Soviets with a choice of continued support from the United States, but only

under the condition that they change their direction toward Poland and Central

Europe (George Kennan, “Memoirs,” pg. 211).

Instead,

Washington stuck with a declaratory policy based on the Atlantic Charter rooted

in Wilsonian principles, but without the power to make good on it. Immediate

victory over Germany took priority, and the United States was not willing to

risk a showdown with Stalin over Poland. Perhaps to its credit, neither was the

Roosevelt administration ready to openly accept a sphere-of-influence

arrangement with Moscow, under which the United States would lock in Stalin’s

post-war cooperation by explicitly recognizing the Soviet Union’s right to “friendly,”

i.e., communist-dominated governments, in Poland, the Baltics, and elsewhere in

Central and Eastern Europe. (This was a live option at the time: Walter

Lippmann, the foremost US foreign policy journalist, had been advocating such

an arrangement as early as 1943; Walter Lippmann, “US Foreign Policy,” pg. 152).

The

United States hoped for the best and approached the Yalta Summit in February

1945 in that spirit. Given Stalin’s subsequent domination of Poland and the

eastern third of Europe, such hope seems fatuous.

Yet soon after

Yalta, Roosevelt re-raised Poland, and pushed Stalin to take seriously the

Declaration’s language about Poland. On April 1, 1945 he wrote to Stalin that a

continuation of the “present Warsaw [Communist-dominated] regime” would be

unacceptable and urged that a “new government” be established. “I must make it

quite plain to you that any such solution which would result in a thinly

disguised continuance of the present Warsaw regime would be unacceptable and

would cause the people of the United States to regard the Yalta agreement as

having failed” (“Foreign Relations of the United States,” 1945, Europe, Volume

V).

What did this

mean? If Roosevelt were serious about applying the Atlantic Charter principles

to Poland and Central Europe, why had he accepted such a weak commitment from

Stalin at Yalta? If Roosevelt’s agreements at Yalta were mere cynical cover for

a sphere-of-influence deal with Stalin, why was Roosevelt trying to raise the

Polish issue at all?

In dealing with

Russian leaders, Roosevelt, like many US presidents after him, appeared to

believe that gestures of good will and efforts to take account of legitimate

Russian interests, would be enough to convince Russia to take a more tolerant

approach to its neighbors. Roosevelt seemed to hope that the momentum of

wartime alliance, and the prospect of post-war entente and US support, would

appeal to Stalin as much as it appealed to him. If so, Roosevelt would not be

the last president to project his open mind to Russian leaders who did not

share it.

Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945. In the final weeks of his life, Roosevelt may have been coming to understand Stalin’s nature. But Yalta Europe, the divided continent that emerged from that Conference despite Roosevelt’s hopes, lasted for another forty-five years.

Yalta offers

lessons.

One is to be

operationally serious: take care when negotiating documents based on general

language of principles, like Yalta’s Declaration of Liberated Europe, with a

leader who shares neither your values nor your underlying purposes. The Joint

Comprehensive Plan of Action (the 2015 Iran nuclear deal), though incomplete

and flawed, was specific and enforceable. The US-North

Korea Joint Statement of 2018, however, was not; in its vague language, it recalls

the Declaration of Liberated Europe.

Another is be

realistic about relative strength, especially in the short term: in its World War Two aims, the United States

allowed a gap to develop between its principles and power on the ground. At

Yalta, that gap left the United States without good options; it relied on

rhetoric and hope instead. Yalta’s reputation for failed aspirations and naïve

(or worse) retreat reflect the baleful consequences of doing so.

A third lesson is that core values may have more viability than it seems, especially in the long term: for two generations after 1945, foreign policy professionals and scholars concluded that Roosevelt’s weak defense of Poland at and immediately after Yalta was pointless (or cynical) and that the principles of the Atlantic Charter were inapplicable east of the Iron Curtain. Soviet domination there, it was implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) accepted, was forever. But it turned out otherwise. The Yalta Conference failed but Yalta Europe was not forever. The strategic vision that Roosevelt spelled out in the Atlantic Charter and sought to realize at Yalta—even if miserably—now seems the right one.

That vision, in

fact, provided the basis for US policy toward Poland and Central Europe after

the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989. That policy sought to fulfill the promise

of the Atlantic Charter for all of Europe—and this time was more successful.

Nor is that narrative over. With respect to Ukraine, a country also seeking a

future with an undivided Europe, those debates and those tensions apply to this

day.

History may have lessons; the history of Yalta surely does.

Daniel Fried is the Weiser Family distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was the coordinator for sanctions policy during the Obama administration, assistant secretary of State for Europe and Eurasia during the Bush administration, and senior director at the National Security Council for the Clinton and Bush administrations. He also served as ambassador to Poland during the Clinton administration.

Further reading:

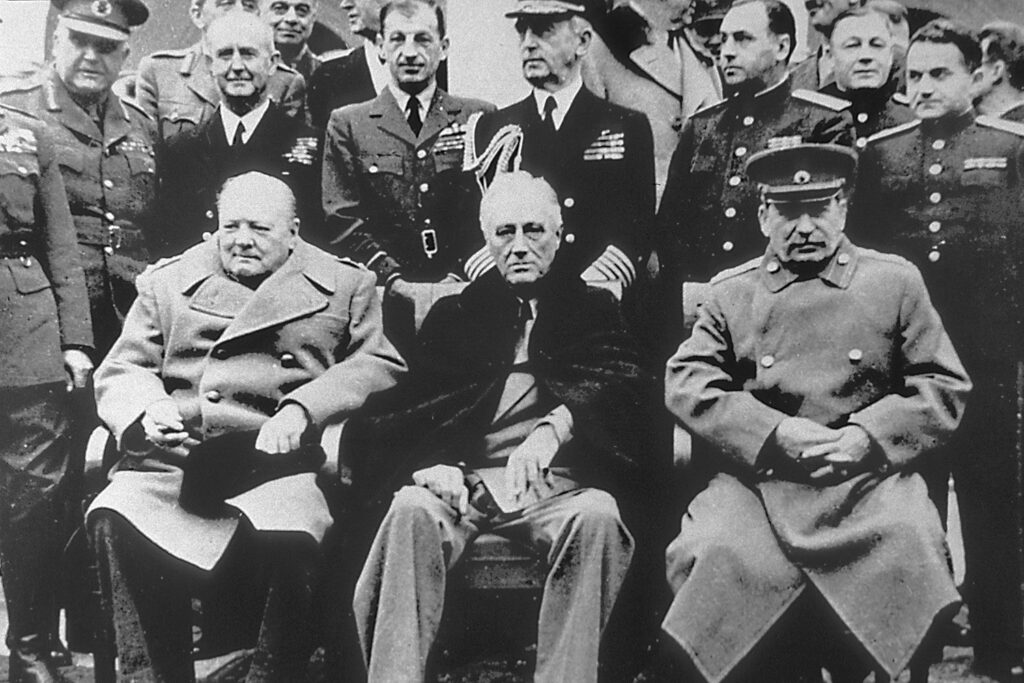

Image: Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Josef Stalin at the Yalta Conference February, 1945 (MPTV Entertainment via REUTERS)

Source link : https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-yalta-conference-at-seventy-five-lessons-from-history/

Author :

Publish date : 2020-02-07 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.