After 40 years, I returned to a stone farmhouse with a view of the Alps out back and vineyards across the road. The kitchen still smelled of roasted potatoes. The window above the sink looked into a courtyard lined with potted laurel trees. I knew which drawer to open to find a loaf of bread, and which cupboard contained the cooking oil.

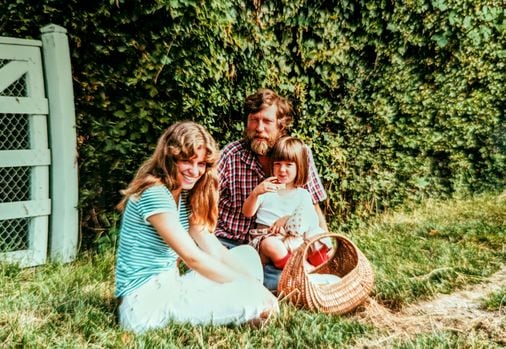

I spent the year after I graduated from college here at this home of a professional winemaker and his family near Geneva, Switzerland. Now Roger and Catherine, the husband and wife, each greeted me with a kiss on both cheeks. We spoke to each other in French, as always. I barely recognized their two children. Their son, who celebrated his first birthday when I lived there, is now a carpenter, married with a child of his own. Their daughter, age 6 when I left, took over the family winemaking business, managing more than 17 acres of vineyards with her husband and four children.

I had returned as a guest, but it felt unnatural to be sitting while they served a festive lunch. During my time as an informal au pair in their home, I helped out with almost every meal. Kitchen work represented a major change from college, where most of my days and nights were spent reading, writing papers, and pontificating. I had signed on to this Swiss gap year experience because I somehow knew I needed a crash course in being part of a joyful, nurturing household after being raised by my widowed mother. Plus, it would be an adventure to spend a year in Europe. While my peers applied to graduate school or interviewed for professional jobs, I bought a plane ticket.

Like many 21-year-olds with a newly minted BA, I had arrived with an inflated sense of self-importance. I was used to being rewarded for expressing my ideas, and to spending most of my time with people my own age. I wanted to go to cafes and stay up late, not wake up before 8 a.m. and start peeling potatoes. Catherine, surprised at my lack of domestic skills, didn’t hesitate to correct me.

Lucky for me, she also showed vast amounts of patience as I learned to how to pitch in with chores without being asked, and to converse instead of retreating with a book. She and Roger wisely let me stumble as I devised ways to entertain each child and adapted to routines that centered around their kitchen table. Along the way, my language skills and understanding of another culture increased.

So did my understanding of family life — its tedium, but also its joys. I felt a special thrill when the baby learned how to walk. I still remember how gleefully he laughed at a simple wind-up toy I bought at a flea market. The daughter delighted in my telling and retelling funny stories about my grandmother, though she made fun of my accent when I read French books to her. I eventually learned to enjoy everyone’s good-natured teasing, and to dish it back.

Once the year ended, I moved to Boston and began a career. Soon after, I met the man I would marry. I lost regular contact with Catherine and Roger, but their influence continued. Because of my year with them, it was easy to imagine starting a family of my own. I knew what to expect and how to better navigate the transition to domestic life. My two children benefited.

When I finally returned to Geneva, I brought my husband and our son, now in his 30s. I felt gratified as I introduced everyone, and once again walked through the vineyards. As we all toasted with a floral Pinot Blanc, one of the wines they produce, I raised my glass to the generous family who had taught me — across language and cultural differences — life lessons I never learned in college.

Clara Silverstein is an author based in Dover. Send comments to [email protected]. TELL YOUR STORY. Email your 650-word unpublished essay on a relationship to [email protected]. Please note: We do not respond to submissions we won’t pursue.

Source link : https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/07/26/magazine/my-practice-family/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-26 20:15:36

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.