Amnesty International’s research highlights the concerning human rights situation in the Samos “Closed Controlled Access Centre”, focusing on the period between July 2023 and January 2024, when increased arrivals led to overcrowding and situations of inadequate conditions and exacerbated residents’ already deficient access to basic services, including water and healthcare. The research documents how, through the so-called “restrictions of freedom” orders imposed by the authorities to new arrivals, residents are systematically subjected to unlawful and arbitrary detention.

The research was conducted between December 2023 and June 2024, and is based on meetings and interviews with residents, representatives of the Greek authorities, civil society organizations and UN agencies.

What is a Closed Controlled Access Centre (CCAC)?

After fires devastated the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesvos in 2020, the European Commission provided €276 million of EU funds for five new “multi-purpose” centres comprising of reception and pre-return detention facilities on the Aegean islands.

The “Closed Controlled Access Centre” on Samos was the first to be opened in 2021 and is located in an isolated area on the outskirts of the main city, Vathi, where most of the civil infrastructure, services and civil society organizations are based.

The centre operates a rigid system of restrictions and surveillance, including double barbed wire metal fencing, CCTV surveillance, digital and physical security infrastructures, and the 24/7 presence of patrolling police and privately contracted security officers.

In April 2024, the Greek Data Protection Authority fined the Greek authorities for the use of security systems, also operated in the Samos centre, due to breaches of data protection legislation.

Security cameras and barbed wire scale the centre creating a ‘prison-like environment’. People did not have enough water or adequate healthcare, and, in some cases, even beds. All the while being unable to leave the centre for weeks, sometimes months on end.

Deprose Muchena, Senior Director, Regional Human Rights Impact at Amnesty International

What is it like to live in the Samos “Closed Controlled Access Centre”?

As a result of increased arrivals from July 2023, the Samos centre experienced overcrowding between September and January 2024, reaching a peak of 4,850 residents in September 2023.

The site’s original capacity was for 2,040 people, but the authorities changed it to 3,650 in September 2023. This change was made without any apparent measures taken to increase accommodation.

This led to some people being housed in non-residential areas and containers, in inadequate conditions, and exacerbated long-standing issues in the provision of basic services, including water shortages and the lack of a permanent medical doctor.

The living conditions of residents, especially during times of overcrowding in the centre, may have amounted to inhumane and degrading conditions, in breach of the prohibition of ill-treatment.

Since February 2024, the number of the residents decreased, and the population has since been within capacity. However, serious shortcomings in the living conditions of residents, including in the provision of medical services and running water, persist.

What restrictions do residents face?

Residents are systematically subjected to“restrictions of freedom” orders, which confine them to the centre for an initial period of 5 days, which can be – and in practice is overwhelmingly – extended up to 25 days in total from when they arrive. Residents and civil society organizations have said that people are often unable to leave the camp for periods exceeding the 25 days, often without a decision on their “restriction of freedom” being officially taken in their case.

On top of the length of these measures, people under “restrictions of freedom” cannot leave the camp, except for “serious health reasons”. These restrictions are routinely applied without an individualized assessment. This goes beyond what can be considered a legitimate restriction of freedom of movement and amounts to unlawful detention.

Unaccompanied minors are accommodated separately in a “safe area”, in a fenced-off sub-section of the “Closed Controlled Access Centre”. But they are subjected to heavy restrictions of movements, including a ban on leaving the centre – except to attend school or, more recently, leisure activities under the supervision of child-protection actors – or even the “safe area” to visit the general population spaces.

These restrictions might constitute an undue interference with their right to liberty, security and their freedom of movement and defy international standards which state that the migration-related detention of children is a violation of their rights and should be prohibited.

“What would you like to share about the Samos CCAC?”

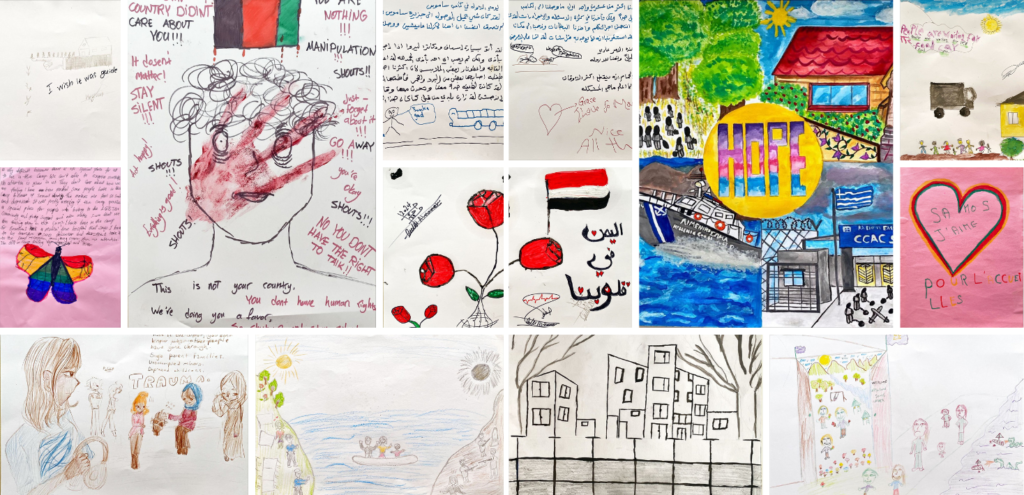

In May 2024, Amnesty International and ‘Samos Volunteers’, a civil society organization that offers informal education, clothing distributions and psycho-social support to people in refugee and migrant communities on Samos, ran art workshops with people who had lived or were still living in the “Closed Controlled Access Centre” (CCAC).

The workshops were attended by people who visit Samos Volunteers’ community centres, as well as people attending the LGBTQI+ support group.

Participants were invited to respond to prompts including: “How do you feel living in the Samos camp?”; “What would you like to change in Samos?”; “What do you hope for in the future?”, using art as a form of expression that crosses boundaries of language and culture.

The artwork presented in this online exhibition shares personal perspectives, feelings, and experiences of life in the camp. The artworks accompany Amnesty International’s new research briefing ‘Samos: “We feel in prison on the island”: Unlawful detention and sub-standard conditions in an EU-funded refugee centre’.

(NOTE: Personal details of the authors of the artwork are included, changed, or wholly omitted depending on their wishes.)

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Artwork by an adolescent living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) – © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Artwork by an adolescent living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) – © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

We are facing mental health issues. I escaped from the war. We left syria to have a better future […] not [to be] here in unsafe, unclean [conditions], difficult for all reasons. I left my family back home and now i feel punished here.

Anwar*, a man from Syria

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Artwork by Zainab, a resident from Afghanistan living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) – © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Artwork by Mohamed, an 18-year-old resident from Sudan living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) – © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

When we arrived in the camp there was water for three hours per day. People couldn’t take showers at the same time. We put water in a jug. We are taking showers as it was done 70 years ago.

Bilal*, from Syria, in the CCAC since 28 September 2023

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Testimony and artwork by Omar, a resident of the Samos CCAC (May 2024) © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Testimony and artwork by Omar, a resident of the Samos CCAC (May 2024) © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Translation of Omar’s artwork

Part 1:

My first day in Samos Camp

Everything was nice. Reaching Samos Island after suffering in Turkey and after “seeing” death at sea, we could not believe that we made it alive and well.

They came in an ambulance and with doctors to check if anyone of us got hurt but no one was hurt, thank God. They gave us food and water and gave us some clothes because most of us got wet at sea. There was this girl who was suffering from chills and fever but the doctor gave her paracetamol. She [the doctor] was so nice with us and told us that she had worked in Yemen before. This made me so happy.

Part 2:

They took us in a big car because there was so many of us. More than 20 people. As soon as we arrived in the camp they gave us food and water. The food was nice but we were delayed because of the many questions and the many procedures. We were so tired all we wanted to do is sleep. After the process [registration] finished, we took our blankets and went to a place they call [illegible]. We arrived there but we were surprised that there were no mattresses and we had to sleep on the floor.

It was a problem for some of us but the others were fine. We turned on the air conditioners because it was cold and we slept after a long journey of adventures and hardship…

We suffer from the water problem. It keeps cutting in the toilets most times.

The asylum process keeps getting delayed and we do not know why.

“I wish there was a guide” – Artwork by Keivan, 32, from Iran living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

“I wish there was a guide” – Artwork by Keivan, 32, from Iran living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) – © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

It is unsafe for my kids, they cannot go to the toilet alone, i need to accompany them. Most of the time my children pee themselves because they are afraid to go out at night.

Ameer*, a man from Palestine

(The) water in the bathroom is dirty and discontinuous… my kids got lice in the hair and cockroaches move on them while they sleep. Kids wake up at night and find the cockroaches walking on them and it is traumatic.

Ameer*, a man from Palestine

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Artwork by a mother of two children living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

“Love Samos – for the welcoming”

Artwork by a woman from Cameroon living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Testimony and artwork by a male resident living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Living in Samos camp as a person that is part of the LGBTQ community is very difficult because there is no special place for us to live in the camp…they don’t care about how we are feeling. I have been mocked. Some people hate in the camp because of sexual identity. This makes me feel so sad and depressed.

A male resident of the Samos CCAC

“My life to Freedom” by Tasneem

© Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

Artwork by Tasneem, a woman from Sudan living in the Samos CCAC (May 2024) © Amnesty International/Samos Volunteers

“The presence of refugees remains a testament to their resilience in the face of difficulties, while they face many challenges. They continue to build a new life and better future, refugees need support to alleviate their suffering. They deserve respect, appreciation and the opportunity to build a new life.

Top-left: This is the forest in Turkey when crossing the border. This is the worst part because it ruins your health and mentality. All you think about is to cross the border. You might expect the police, you might even go to prison and face deportation back to your country before you make the crossing.

Bottom-left: This part has different fates – you might make it to Samos or you might be violently pushed back to Turkey. People here can face death in the sea.

Bottom-right: This is the shock. You think you will find a very nice situation, but everything is the opposite. It’s prison. They say this is Europe, this is freedom – but it is not like this.

Top-right: This the dream. This is the good life. Everyone dreams for this moment – to have your own house, your own life, no more troubles, forget your suffering.”

This is all related to hope. Each stage you hope for the next stage. And in the end, you hope to have a good life for you and your family.

Tasneem

This cannot be the model for the EU’s Migration and Asylum Pact

The European Commission’s support for the creation and operation of the Samos centre, and in the other “Closed Controlled Access Centres” on the Greek islands, enhances its responsibilities for any resulting violations.

Like all new EU-funded centres, the Samos camp is designed to comply with the principles underpinning the EU’s Migration and Asylum Pact, a set of recently adopted reforms to EU asylum law.

Amnesty International has consistently expressed concern that the Pact would weaken access to asylum and increase the risk of human rights violations and de facto detention, notably through the restrictions to peoples’ movements while undergoing the screening, border asylum and border return procedures.

The EU must hold Greece accountable for human rights violations in the centre and ensure that model is not a blueprint for members states implementing the new Migration and Asylum Pact.

We can do better

As Tasneem shows us with her artwork, “My Life to Freedom”, hope is not lost.

Greece and the EU still have the opportunity to act to improve living conditions for people awaiting their asylum application decisions and to ensure human rights and basic humane treatment are upheld.

Here’s how you can help put pressure on the EU to act:

@YlvaJohansson @EUHomeAffairs Ensure Samos refugee camp is not a blueprint for EU Migration Pact. EU funds must not finance human rights abuses

🔍Scrutinize camp conditions

🚨Advance infringement proceedings against #Greece

📋Ensure the Pact does not result in violations

* NOTE: Pseudonyms have been assigned to all CCAC residents interviewed.

Source link : https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2024/07/people-seeking-asylum-detained-in-samos-camp-in-greece/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-30 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.