Germany and Malta: respectively, the largest absolute number of total immigrants and the highest rate of immigration in 2022

Germany reported the largest total number of immigrants (2.1 million) in 2022, followed by Spain (1.3 million), France (0.4 million) and Italy (0.4 million). Germany also reported the highest number of emigrants in 2022 (533 500), followed by Spain (531 900), France (249 400), Poland (228 000) and Romania (202 300). In 2022, all 27 EU Member States reported more immigration than emigration, while in 2021 in 4 EU Member States (Croatia, Greece, Latvia and Romania) there were more emigrants than immigrants. Additionally, compared with 2021, all Member States with the exception of Slovakia recorded an increase in the total number of immigrants in 2022: the highest increases in relative terms between 2021 and 2022 were observed in Czechia (401 %), Latvia (205 %), Estonia (153 %), Germany (137 %) and Portugal (132 %).

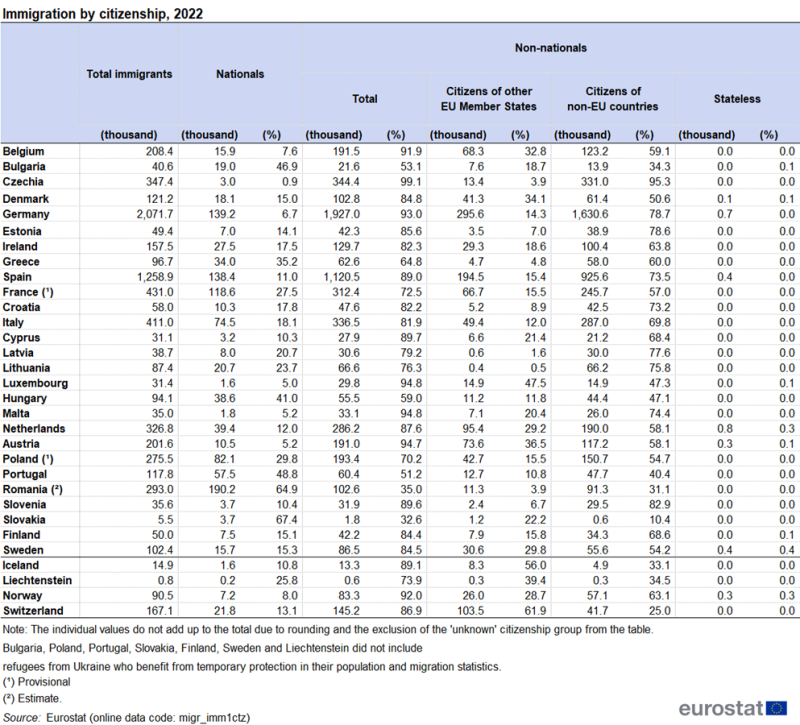

Table 1: Immigration by citizenship, 2022

Table 1: Immigration by citizenship, 2022

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz)

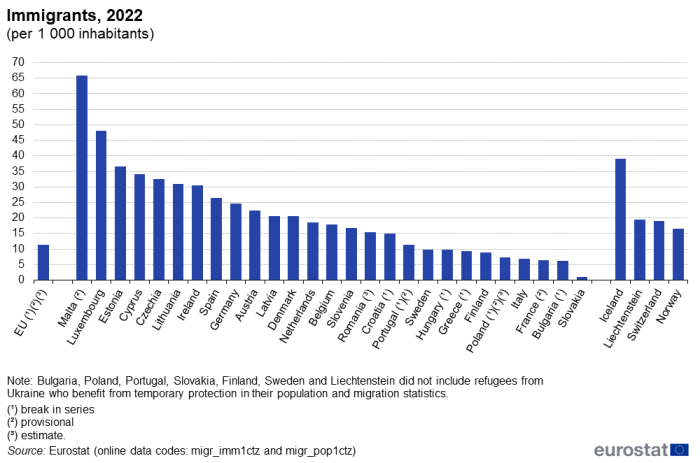

Relative to the size of the resident population, Malta recorded the highest rate of immigration in 2022 (almost 66 immigrants per 1 000 persons), followed by Luxembourg (48 immigrants per 1 000 persons), Estonia (37 immigrants per 1 000 persons), Cyprus (34 immigrants per 1 000 persons), Czechia (33 immigrants per 1 000 persons), Lithuania (31 immigrants per 1 000 persons) and Ireland (30 immigrants per 1 000 persons) — see Figure 2. For emigration, the highest rates in 2022 were reported for Luxembourg (26 emigrants per 1 000 persons), Malta (25 emigrants per 1 000 persons) and Cyprus (20 emigrants per 1 000 persons). In 2021, the highest rates of immigration were recorded in Luxembourg (40 immigrants per 1 000 persons), Malta (35 immigrants per 1 000 persons), Cyprus (27 immigrants per 1 000 persons), Spain (19 immigrants per 1 000 persons) and Ireland (16 immigrants per 1 000 persons), whereas the highest rates of emigration were reported for Malta (26 emigrants per 1 000 persons), Luxembourg (25 emigrants per 1 000 persons) and Cyprus (20 emigrants per 1 000 persons).

Highest share of national immigrants for Slovakia, lowest for Czechia

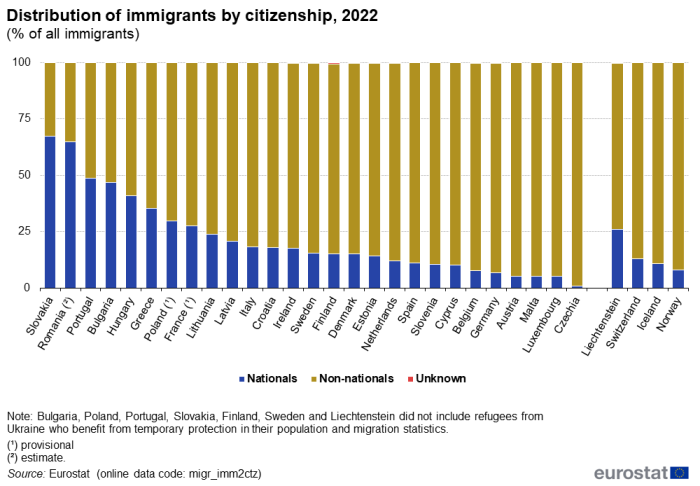

In 2022, the relative share of national immigrants (immigrants with the citizenship of the EU Member State to which they were migrating) within the total number of immigrants was highest in Slovakia (67.4 % of all immigrants) and Romania (64.9 %). These were the only EU Member States where national immigration accounted for more than half of the total number of immigrants — see Figure 3. By contrast, in Czechia, immigration of nationals represented 0.9 % of total immigration in 2022. In 2021, in five EU Member States, Romania, Portugal, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Lithuania, national immigration accounted for more than half of the total number of immigrants, while Czechia was again the country with the lowest proportion (4.2 %).

Figure 3: Distribution of immigrants by citizenship, 2022

Figure 3: Distribution of immigrants by citizenship, 2022

(% of all immigrants)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm2ctz)

Information on citizenship has often been used to study immigrants with a foreign background. However, as citizenship can change over the lifetime of a person, it is also useful to analyse information by country of birth. The relative share of native-born immigrants within the total number of immigrants was highest in Romania (43.8 % of all immigrants), followed by Bulgaria (36.7 %) and Greece (31.2 %). In contrast, Czechia (1.3 % of all immigrants), Luxembourg (4.0 %) and Austria (4.0 %) reported the lowest shares of native-born immigrants. In 2021, Romania (52.4 %), Bulgaria (48.1 %) and Greece (47.8 %) again reported the highest share of native-born immigrants, while Luxembourg (5.0 %), Austria (6.4 %) and Czechia (7.4 %) reported the lowest shares of native-born immigrants.

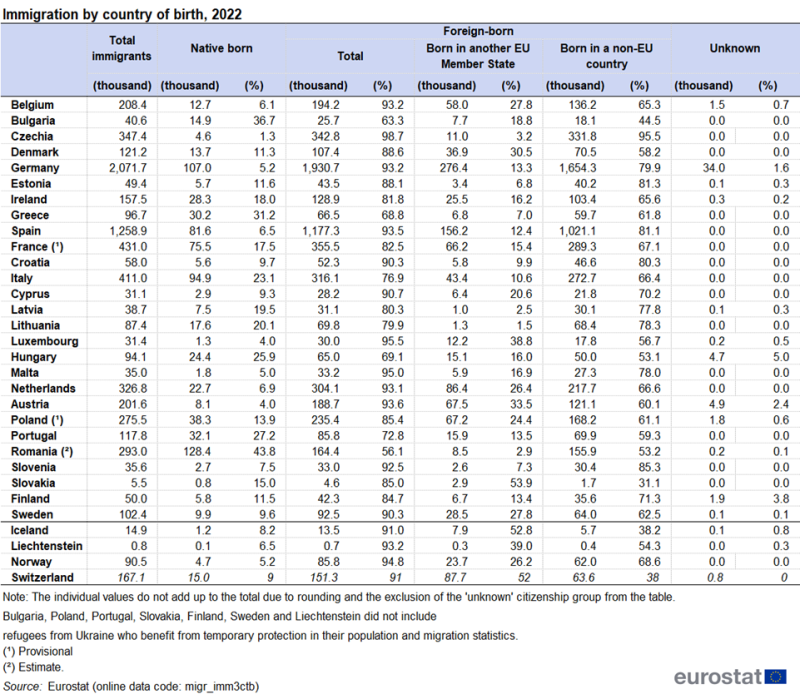

Table 2: Immigration by country of birth, 2022

Table 2: Immigration by country of birth, 2022

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm3ctb)

Previous residence: 5.1 million immigrants entered the EU in 2022

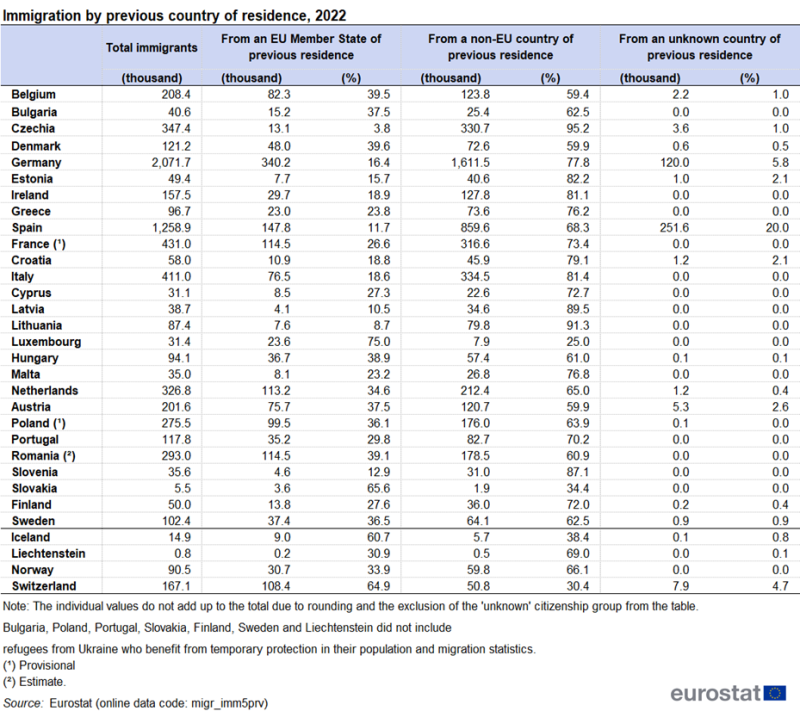

An analysis by place of previous residence (see Table 3) reveals that Czechia recorded the largest share of immigrants coming from outside the EU (95.2 % of its total number of immigrants in 2022), followed by Lithuania (91.3 %) and Latvia (89.5 %). On the other hand, Luxembourg reported the largest share of immigrants coming from another EU Member State (75.0 % of its total number of immigrants in 2022), followed by Slovakia (65.6 %). In 2021, Lithuania recorded the largest share of immigrants coming from outside the EU (81.4 % of its total number of immigrants in 2021), followed by Slovenia (78.8 %), Italy (78.0 %) and Czechia (78.0 %), while Luxembourg (91.0 %), Slovakia (67.9 %) and Austria (56.0 %) reported the largest share of immigrants coming from another EU Member State.

Table 3: Immigration by previous country of residence, 2022

Table 3: Immigration by previous country of residence, 2022

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm5prv)

Moreover, since 5.1 million is the highest value of immigration from non-EU countries recorded in the time series starting in 2013, immigration by country of previous residence can give some indication of what drives this change. However, only Czechia, Estonia, Spain, Croatia, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Austria, Romania and Slovenia provided immigration statistics by country of previous residence and included refugees from Ukraine who benefit from temporary protection in their migration statistics. Among them, 60 % of the increase in immigration from non-EU countries from 2021 to 2022 was explained by the change in immigration from Ukraine. However, it is important to underline that these countries may not be representative of the EU as a whole, and the total change in immigration is also explained by other factors in the migrants’ countries of origin and destination.

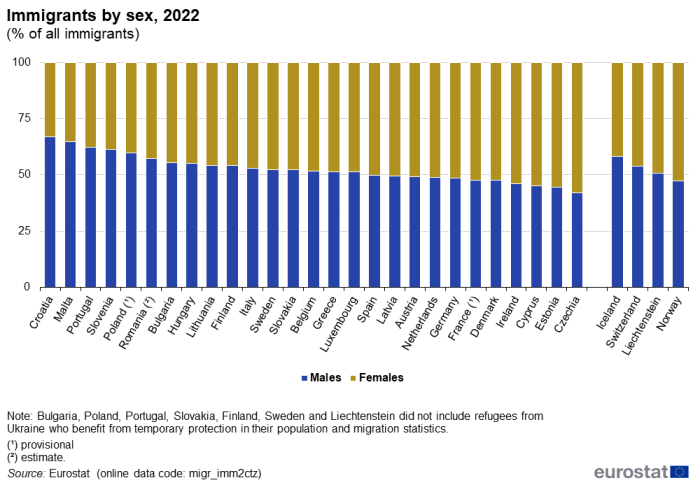

Sex distribution of immigrants to the EU Member States in 2022

Approximately the same proportion of men and women immigrated to the EU Member States in 2022 (50.4 % compared with 49.6 %). In 2021, more men than women immigrated to the EU Member States (55.1 % compared with 44.9 %). In 2022, the Member State reporting the highest share of male immigrants was Croatia (67.0 %); in contrast, the highest share of female immigrants was reported in Czechia (57.9 %). In 2021, the Member State reporting the highest share of male immigrants was again Croatia (72.7 %), while the highest share of female immigrants was reported in Cyprus (53.5 %).

Figure 4: Immigrants by sex, 2022

Figure 4: Immigrants by sex, 2022

(% of all immigrants)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm2ctz)

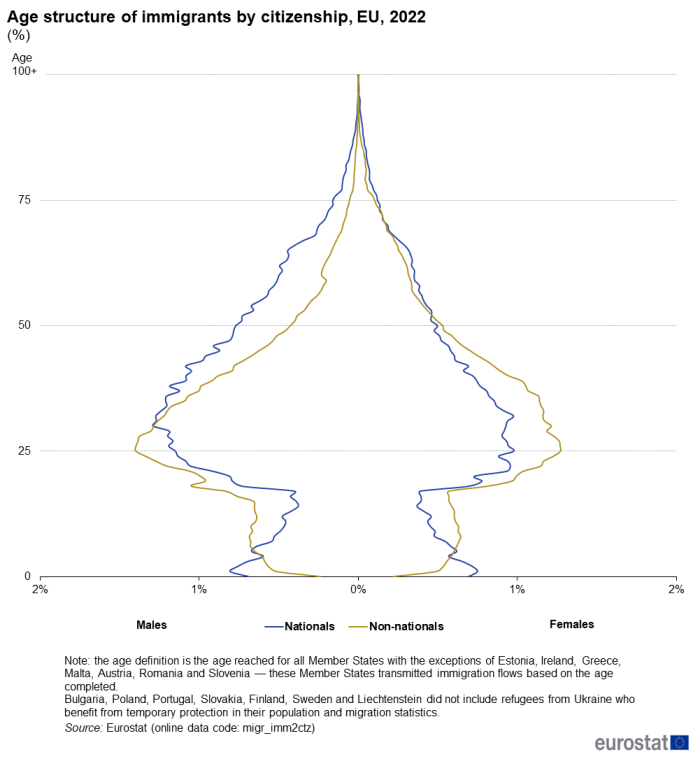

Half of immigrants were aged under 31 years

Immigrants were, on average, younger than the already resident population of EU Member States. On 1 January 2023, the median age of the total population of the EU stood at 44.5 years, while it was 30.5 years for immigrants in 2022.

An analysis of the age structure of immigrants by citizenship shows that, for the EU as a whole, the non-national immigrants were younger than the national immigrants. The distribution by age of non-national immigrants shows, compared with national immigrants, a greater proportion of relatively young working age adults. The median age of national immigrants stood at 33.5 years and that of non-national immigrants was 30.0 years.

Figure 5: Age structure of immigrants by citizenship, EU, 2022

Figure 5: Age structure of immigrants by citizenship, EU, 2022

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm2ctz)

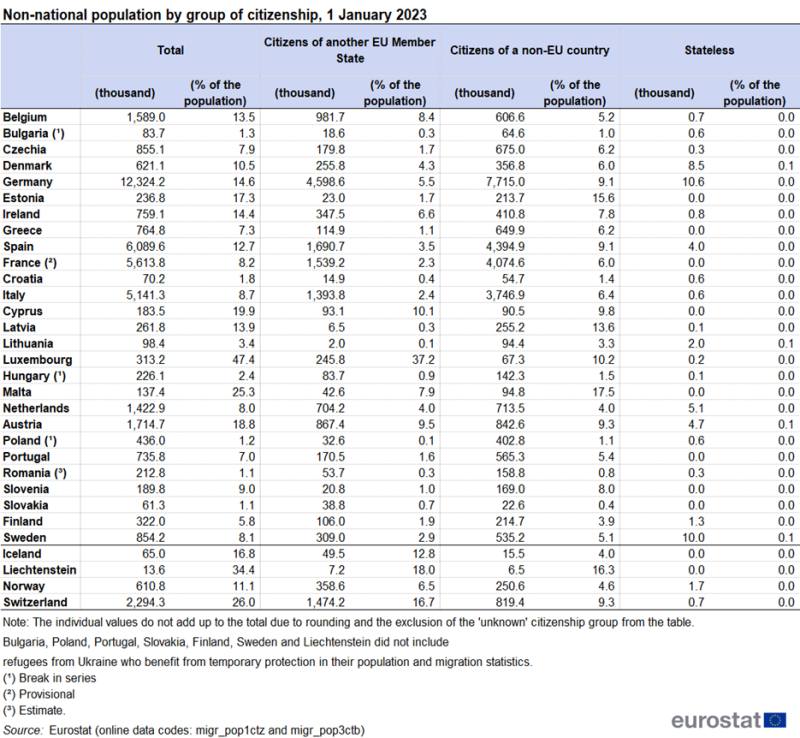

Migrant population: 27.3 million non-EU citizens living in the EU on 1 January 2023

On 1 January 2023, 27.3 million citizens of non-member countries were residing in an EU Member State, representing 6.1 % of the EU population. This represents an increase of 3.5 million compared to the previous year. In addition, 13.9 million persons living in one of the EU Member States on 1 January 2023 were citizens of another EU Member State.

In absolute terms, the largest numbers of non-nationals living in the EU Member States on 1 January 2023 were found in Germany (12.3 million), Spain (6.1 million), France (5.6 million) and Italy (5.1 million). Non-nationals in these four Member States collectively represented 70.6 % of the total number of non-nationals living in the EU, while the same four Member States had a 57.9 % share of the EU’s population.

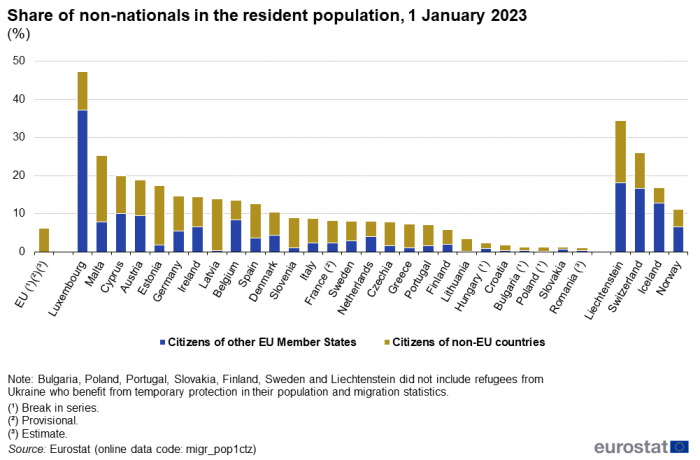

In relative terms, the EU Member State with the highest share of non-nationals on 1 January 2023 was Luxembourg, where non-nationals accounted for 47.4 % of the total population. High proportions of foreign citizens (more than 10 % of the resident population) were also observed in Malta (25.3 %), Cyprus (19.9 %), Austria (18.8 %), Estonia (17.3 %), Germany (14.6 %), Ireland (14.4 %), Latvia (13.9 %), Belgium (13.5 %), Spain (12.7 %) and Denmark (10.5 %). In contrast, non-nationals represented less than 3 % of the population in Romania (1.1 %), Slovakia (1.1 %), Poland (1.2 %), Bulgaria (1.3 %), Croatia (1.8 %) and Hungary (2.4 %).

Table 4: Non-national population by group of citizenship, 1 January 2023

Table 4: Non-national population by group of citizenship, 1 January 2023

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

Non-national population in the EU Member States: mostly non-EU citizens

On 1 January 2023, in most EU Member States, the majority of non-nationals were citizens of non-EU countries (see Figure 6). Only in Luxembourg, Cyprus, Austria, Belgium and Slovakia did citizens of another EU Member State make up more than 50 %. In the case of Latvia, the proportion of citizens from non-member countries is particularly large due to the high number of recognised non-citizens (mainly former Soviet Union citizens, who are permanently resident in these countries but have not acquired any other citizenship).

Figure 6: Share of non-nationals in the resident population, 1 January 2023

Figure 6: Share of non-nationals in the resident population, 1 January 2023

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

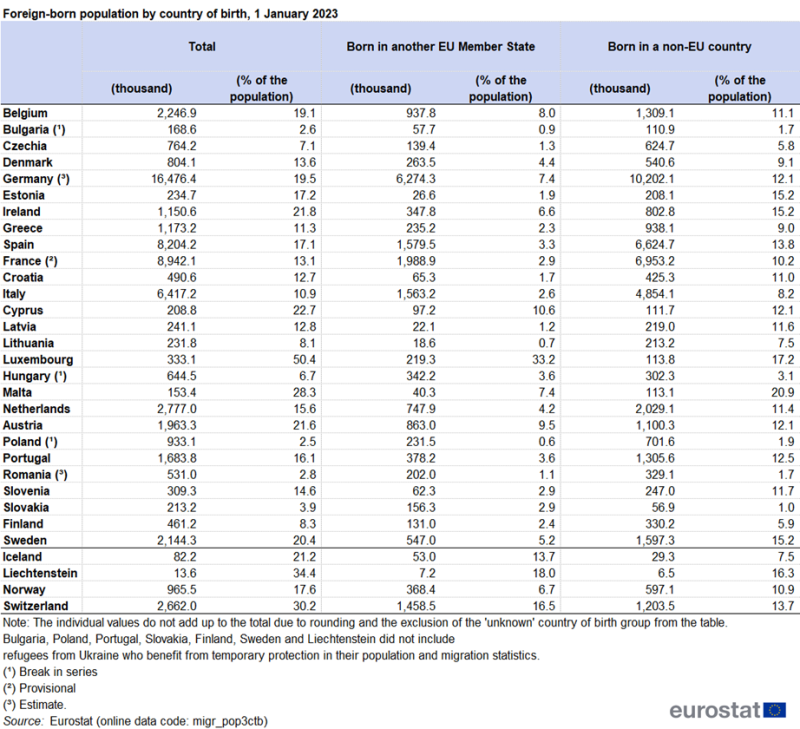

Highest share of foreign-born population in Luxembourg, lowest in Poland

The relative share of foreign-born within the total population was highest in Luxembourg (50.4 % of the resident population), followed by Malta (28.3 %), Cyprus (22.7 %), Ireland (21.8 %) and Austria (21.6 %). In contrast, Poland reported a low share of foreign-born (2.5 % of its total population on 1 January 2022), followed by Bulgaria (2.6 %), Romania (2.8 %) and Slovakia (3.9 %).

In relative terms, Luxembourg had also by far the largest share of population born in other EU countries, 33.2 %, followed by Cyprus with 10.6 %, Austria with 9.5 % and Belgium with 8.0 %. Germany and Malta also registered high shares of citizens born in other EU countries, with 7.4 % each. Poland (0.6 % of the resident population) and Lithuania (0.7 % of the resident population) on the other hand, had the smallest shares of population born in other EU countries.

Table 5: Foreign-born population by country of birth, 1 January 2023

Table 5: Foreign-born population by country of birth, 1 January 2023

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop3ctb)

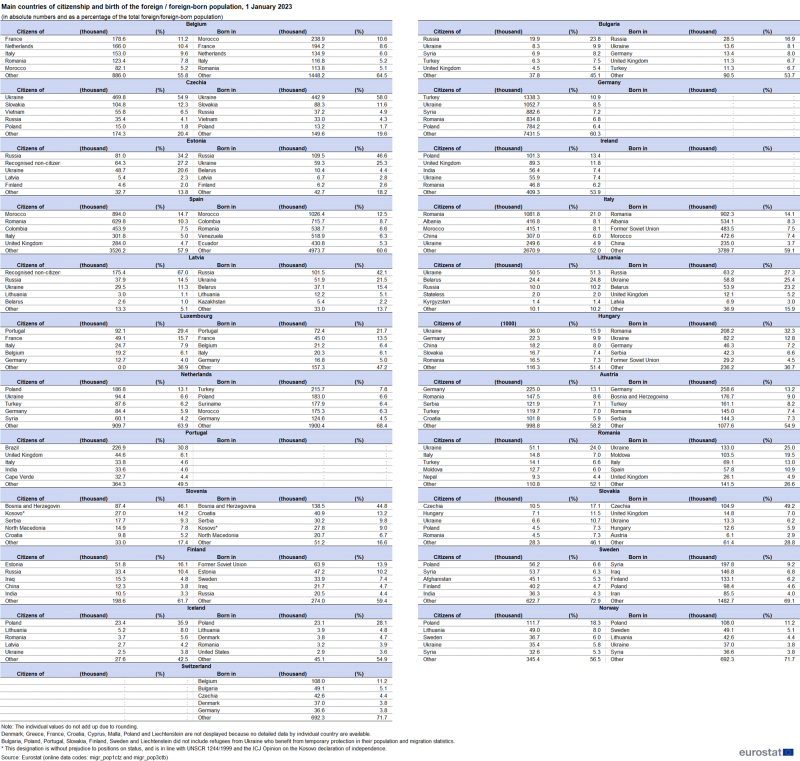

Table 6 presents a summary of the five main groups of foreign citizens and foreign-born populations for the EU Member States and EFTA countries (subject to data availability).

Table 6: Main countries of citizenship and birth of the foreign/foreign-born population, 1 January 2023

Table 6: Main countries of citizenship and birth of the foreign/foreign-born population, 1 January 2023

(in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the total foreign/foreign-born population)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz) and (migr_pop3ctb)

Table 6 ![]() is available here.

is available here.

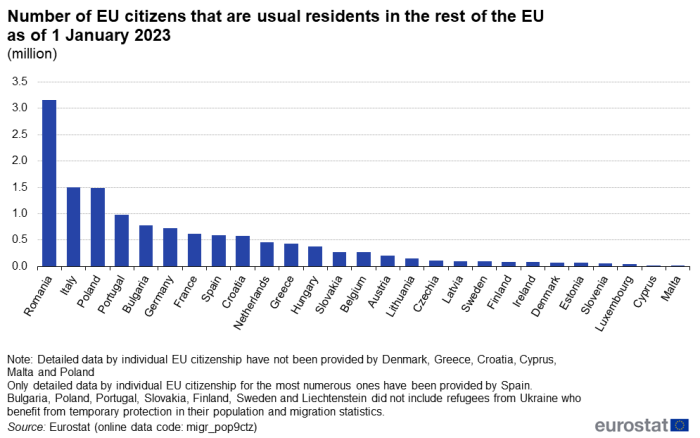

Romanian, Italian and Polish citizens were the three largest groups of EU citizens living in other EU Member States on 1 January 2023 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Number of EU citizens that are usual residents in the rest of the EU as of 1 January 2023

Figure 7: Number of EU citizens that are usual residents in the rest of the EU as of 1 January 2023

(million)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop9ctz)

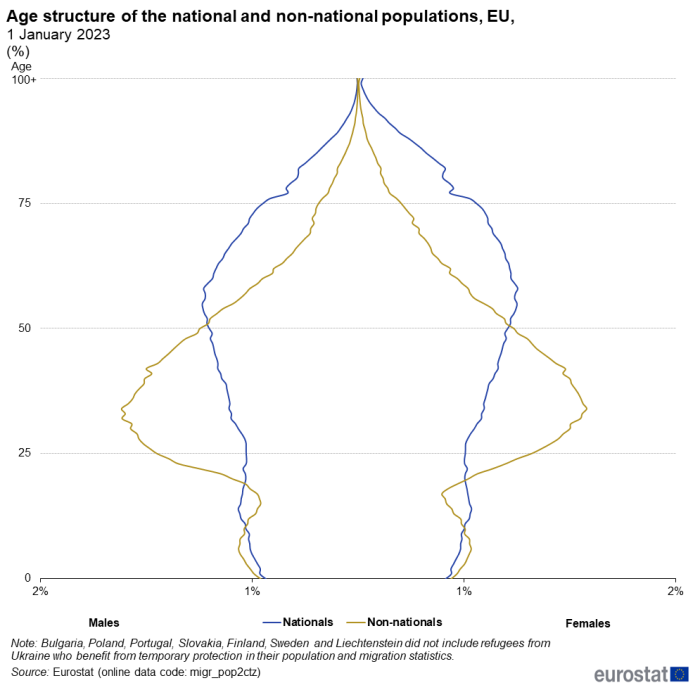

Foreign citizens are younger than nationals

An analysis of the age structure of the population shows that, for the EU as a whole, the foreign population was younger than the national population. The distribution by age of foreigners shows, compared with nationals, a greater proportion of relatively young working age adults. On 1 January 2023, the median age of the national population in the EU was 45.7 years, while the median age of non-nationals living in the EU was 36.5 years.

Figure 8: Age structure of the national and non-national populations, EU, 1 January 2023

Figure 8: Age structure of the national and non-national populations, EU, 1 January 2023

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Emigration is particularly difficult to measure. It is harder to keep track of people leaving a country than those arriving, because for a migrant it is very often much more important to interact about his/her migration with the authorities of the receiving country than with those of the country he/she is leaving. An analysis comparing 2019 immigration with emigration data from the EU Member States (mirror statistics) confirmed that this was true in many countries — as a result, this article focuses on immigration data.

Eurostat produces statistics on a range of issues related to international migration flows, non-national population stocks and the acquisition of citizenship. Data are collected on an annual basis and are supplied to Eurostat by the national statistical authorities of the EU Member States and EFTA countries.

Data in this article are rounded to the nearest hundred.

Legal Sources

Since 2008 the collection of migration and international protection data has been based on Regulation (EC) No 862/2007 and the analysis and composition of the EU, EFTA and candidate countries groups as of 1 January of the reference year are given in the implementing Commission Regulation (EU) No 351/2010. This defines a core set of statistics on international migration flows, population stocks of foreigners, the acquisition of citizenship, residence permits, asylum and measures against illegal entry and stay. Although EU Member States may use any appropriate data sources according to national availability and practice, the statistics collected under the Regulation must comply with common definitions and concepts. Most EU Member States base their statistics on administrative data sources such as population registers, registers of foreigners, registers of residence or work permits, health insurance registers and tax registers. Some countries use mirror statistics (for example, country X may use for immigration from country Y the emigration flows reported by country Y as coming from country X), sample surveys or estimation methods to produce migration statistics.

As stated in Article 2.1(a), (b), (c) of Regulation (EC) No 862/2007, immigrants who have been residing (or who are expected to reside) in the territory of an EU Member State for a period of at least 12 months are included in the statistics, as are emigrants living abroad for more than 12 months. Therefore, data collected by Eurostat concern migration for a period of 12 months or longer. Migrants therefore include people who have migrated for a period of one year or more as well as persons who have migrated on a permanent basis. Data on acquisitions of citizenship are collected by Eurostat under the provisions of Article 3.1.(d) of Regulation 862/2007, which states that: ‘Member States shall supply to the Commission (Eurostat) statistics on the numbers of (…) persons having their usual residence in the territory of the Member State and having acquired during the reference year the citizenship of the Member State (…) disaggregated by (…) the former citizenship of the persons concerned and by whether the person was formerly stateless’.

Definitions:

Age:

Concerning the definitions of age for migration flows, please note that 2022 data concern the respondent’s age reached or age at the end of the reference year for all EU Member States with the exception of Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Malta, Austria, Romania and Slovenia. In these countries data concern the respondent’s age completed or on their last birthday.

Member States and EFTA countries by inclusion/exclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in the data on population reported to Eurostat in the framework of the Unified Demographic data collection Reference Year 2022

Population as of 01.01.2023

Included

Excluded

Asylum seekers usually resident for at least 12 months

Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Norway, Switzerland

Bulgaria, Denmark, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein

Refugees usually resident for at least 12 months

Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland

Refugees from Ukraine who benefit from temporary protection in the EU

Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Romania, Slovenia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland

Bulgaria, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Liechtenstein

Member States and EFTA countries by inclusion/exclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in the data on migration reported to Eurostat in the framework of the Unified Demographic data collection Reference Year 2022

Migration for 2022

Included

Excluded

Asylum seekers usually resident for at least 12 months

Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Norway, Switzerland

Bulgaria, Denmark, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein

Refugees usually resident for at least 12 months

Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland

Refugees from Ukraine who benefit from temporary protection in the EU (¹)

Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Romania, Slovenia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland

Bulgaria, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Liechtenstein

(¹) On 2 March 2022, the Commission activated the Temporary Protection Directive to offer quick and effective assistance to people fleeing the war in Ukraine. Under this proposal, those fleeing the war will be granted temporary protection in the EU, meaning that they will be given a residence permit, and they will have access to education and to the labour market. See Context for additional information.

Refugee: The term does not solely refer to persons granted refugee status (as defined in Art.2(e) of Directive 2011/95/EC within the meaning of Art.1 of the Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees of 28 July 1951, as amended by the New York Protocol of 31 January 1967) but also to persons granted subsidiary protection (as defined in Art.2(g) of Directive 2011/95/EC) and persons covered by a decision granting authorisation to stay for humanitarian reasons under national laws concerning international protection.

Asylum seeker: First-time asylum applications are country-specific and imply no time limit. Therefore, an asylum seeker can apply for the first time in a given country and afterwards again as first-time applicant in any other country. If an asylum seeker lodges once more an application in the same country after any period of time, (s)he is not considered again a first-time applicant.

Methodological notes:

Following Eurostat’s recommendations to ensure consistency of statistics over time, several Member States (Bulgaria, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Norway) have revised or are in process of revising their population or migration time series between the reference years of the population and housing censuses held in 2011 and 2021.

Guidance on the inclusion of refugees from Ukraine who benefit from temporary protection in the EU in the usually resident population:

persons from Ukraine granted temporary protection should be counted as part of the usually resident population. Based on this, those who arrived from Ukraine and were granted temporary protection during the year – and who are believed to still be present at the end of the year – should be counted as immigrants during the year and as part of the migrant stock at the end of the reference period.

Context

Citizens of EU Member States have freedom to travel and freedom of movement within the EU’s internal borders. Migration policies within the EU in relation to citizens of non-member countries are increasingly concerned with attracting a particular migrant profile, often in an attempt to alleviate specific skills shortages. Selection can be carried out on the basis of language proficiency, work experience, education and age. Alternatively, employers can make the selection so that migrants already have a job upon their arrival.

Besides policies to encourage labour recruitment, immigration policy is often focused on two areas: preventing unauthorised migration and the illegal employment of migrants who are not permitted to work, as well as promoting the integration of immigrants into society. Significant resources have been mobilised to fight people smuggling and trafficking networks in the EU.

Within the European Commission, the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs is responsible for the European migration policies. In 2005, the European Commission relaunched the debate on the need for a common set of rules for the admission of economic migrants with a Green paper on an EU approach to managing economic migration (COM(2004) 811 final) which led to the adoption of a policy plan on legal migration (COM(2005) 669 final) at the end of 2005. In July 2006, the European Commission adopted a Communication on policy priorities in the fight against illegal immigration of third-country nationals (COM(2006) 402 final), which aims to strike a balance between security and an individuals’ basic rights during all stages of the illegal immigration process. In September 2007, the European Commission presented its third annual report on migration and integration (COM(2007) 512 final). A European Commission Communication adopted in October 2008 emphasised the importance of strengthening the global approach to migration: increasing coordination, coherence and synergies (COM(2008) 611 final) as an aspect of external and development policy. The Stockholm programme, adopted by EU heads of state and government in December 2009, set a framework and series of principles for the ongoing development of European policies on justice and home affairs for the period 2010 to 2014; migration-related issues are a central part of this programme. In order to bring about the changes agreed upon, the European Commission enacted an action plan implementing the Stockholm programme – delivering an area of freedom, security and justice for Europe’s citizens (COM(2010) 171 final) in 2010.

In May 2013, the European Commission published the ‘EU Citizenship Report 2013’ (COM(2013) 269 final). The report noted that EU citizenship brings new rights and opportunities. Moving and living freely within the EU is the right most closely associated with EU citizenship. Given modern technology and the fact that it is now easier to travel, freedom of movement allows Europeans to expand their horizons beyond national borders, to leave their country for shorter or longer periods, to come and go between EU countries to work, study and train, to travel for business or for leisure, or to shop across borders. Free movement potentially increases social and cultural interactions within the EU and closer bonds between EU citizens. In addition, it may generate mutual economic benefits for businesses and consumers, including those who remain at home, as internal obstacles are steadily removed.

The European Commission presented a European Agenda on Migration (COM(2015) 240 final) outlining immediate measures to be taken in order to respond to the crisis situation in the Mediterranean as well as steps to be taken in the coming years to better manage migration in all its aspects on 13 May 2015.

The European migration network started publishing in 2016 annual reports on migration. They provide an overview of the main legal and policy developments taking place across the EU as a whole and within participating countries. They are comprehensive documents and covers all aspects of migration and asylum policy by the European Commission’s Migration and Home Affairs and EU agencies.

On 15 November 2017, the updated European Agenda on Migration focused on the refugee crisis, a common visa policy and Schengen. Matters included resettlements and relocations, financial support to Greece and Italy, and facilities for refugees. Objectives included enabling refugees to reach Europe through legal and safe pathways, ensuring that relocation responsibility is shared fairly between Member States, integrating migrants at local and regional levels.

On 4 December 2018, the Commission published a progress report on the implementation of the European Agenda on Migration, examining progress made and shortcomings in the implementation of the European Agenda on Migration. Focusing on how climate change, demography and economic factors create new reasons pushing people to move, it confirmed that the drivers behind migratory pressure on Europe were structural, thus making it all the more essential to deal with the matter efficiently and uniformly.

On 16 October 2019, the Commission published a progress report on the implementation of the European Agenda on Migration, focusing on key steps required on the Mediterranean routes in particular, as well as actions to consolidate the EU’s toolbox on migration, borders and asylum.

On 23 September 2020, the Commission presented a New Pact on Migration and Asylum, setting out a fairer, more European approach to managing migration and asylum. It aims to put in place a comprehensive and sustainable policy, providing a humane and effective long-term response to the current challenges of irregular migration, developing legal migration pathways, better integrating refugees and other newcomers, and deepening migration partnerships with countries of origin and transit for mutual benefit. In December 2023, the European Parliament and the Council reached political agreement on the New Pact on Migration and Asylum.

On 2 March 2022, the Commission activated the Temporary Protection Directive to offer quick and effective assistance to people fleeing the war in Ukraine. Under this proposal, those fleeing the war will be granted temporary protection in the EU, meaning that they will be given a residence permit, and they will have access to education and to the labour market. The Commission created a solidarity platform to coordinate the reception of displaced people in the Member States. The EU Migration Preparedness and Crisis Management Mechanism Network, which gathers and disseminates information on the latest developments, strengthened the EU’s collective response.

Some of the most important legal texts adopted in the area of immigration include:

For more information please see the New pact on Migration and Asylum

Source link : https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics

Author :

Publish date : 2024-04-02 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.