Although it had received the status of Project of Common Interest by the European Commission as early as November 2014, this FSRU was inaugurated only in May 2022, in presence of the President of the European Council, of the leaders of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia, and of the new US ambassador in Athens. The latter has consistently expressed support to the project, rallying also Moldova and Ukraine. Besides, the Bulgarian company Bulgartransgaz has secured a 20-percent stake, as this unit is set to become key in the realization of the Vertical Corridor, the gas pipeline network connecting Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, Moldova, and Ukraine. Strongly backed by Washington, the Vertical Corridor is also expected to obtain EU funding.

Therefore, via the energy vector, Alexandroupolis is expanding its strategic role, as even Moldova and Ukraine are now target gas recipients from its facilities with a view to facilitate their integration into the Western energy, economic and infrastructural system. In this respect, the fact that the Greek operator DEPA won the tender to supply gas to the Moldovan national company Energocom in 2023 and that the Greek Public Power Corporation actively invests in the Romanian energy market demonstrates Athens’ interest in this region.

This FSRU project is coupled with two other energy projects. Firstly, a natural gas-fired electricity generation plant designed to meet local and regional consumption needs in order to increase Greece’s role in the energy security of Southeast Europe. It is expected to be operational in 2026. Secondly, a pipeline linking Alexandroupolis to Burgas, to enable Bulgaria to reduce its high dependence on Russian oil. It is the same pipeline that was planned in the 1990s, but in the opposite direction: it is now designed to provide Bulgaria with oil and gas arriving by sea through Alexandroupolis. Undoubtedly, this is the epitome of the correlation between geopolitical upheaval and the reorganisation of energy routes.

All in all, this enterprising mindset in the energy field is part of Greece’s efforts to optimise its position as the first continental EU country located on the maritime route connecting the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region and the Indo-Pacific to Europe, while it evidences Alexandroupolis’ key position in this scheme. That said, nothing should be taken for granted. This reorganization of energy routes that benefits Greece is an ongoing process. Therefore, it is vulnerable to vagaries and counter-strategies. It is true that the EU has decreased its gas imports from Russia from 175-180 bcm in 2018-2019 to 63,8 in 2022 and 28,3 in 2023, marking an all-post-Soviet time low. However, in the first half of 2024, imports of Russian piped natural gas (PNG) increased by 24 percent on a year-to-year basis. In the same period, the import of LNG has dropped by 20 percent, including due to the increase in PNG imports. Prominent Greek analysts have claimed that Russia started to artificially decrease the price of PNG destined to the EU in late 2023 precisely in order to cancel the dynamic of the Vertical Corridor before it acquires economic viability. At the same time, Ukraine, via which half of the Russian PNG destined to the EU still transits, will probably not extend its contract with Gazprom, which expires at the end of 2024. It remains to be seen whether this will boost LNG imports, including through Greece, or if Turkstream, via which the other half of Russian PNG transits, will see a further increase in deliveries (also taking into account the face that PNG remains cheaper than LNG).

The transport infrastructure dimension

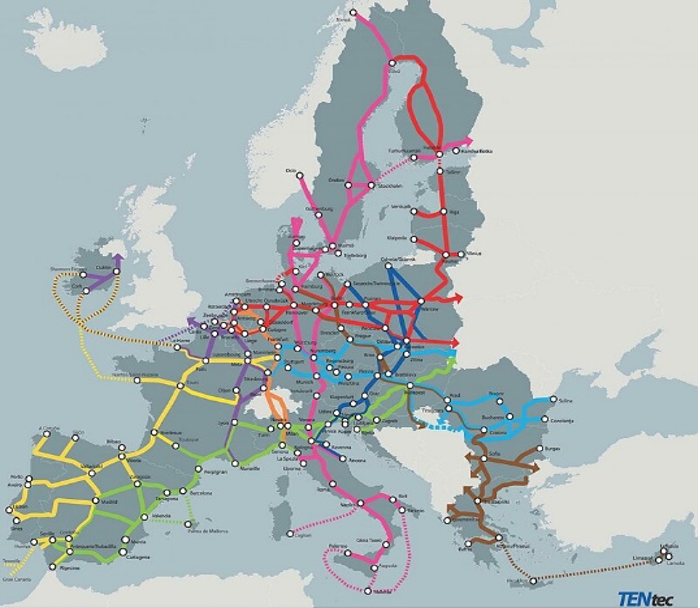

The war in Ukraine has crystallised the East-West rupture along EU/NATO’s eastern flank, generating the need to strengthen the North-South axis linking the Baltic to the Aegean. This implies addressing a recurring shortcoming of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), which has remained essentially structured on an East-West logic.

The TEN-T

Source: Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Indeed, cross-border connections between the EU and Russia/Belarus become increasingly random. Among other, this severely affects the Baltic states and their ports, given that, as former Soviet republics, they remain better connected to Russia and Belarus, while the exclave of Kaliningrad on their south-western flank further complicates their connection to the EU. Accordingly, this East-West rupture in the centre of geographical Europe raises new needs in terms of logistic solidarity and connectivity. Russia and Belarus are increasingly looking North, South and East for solutions. On their side, the EU, as well as the US, the UK and even Switzerland and Japan display commitment to strengthening North-South connectivity, including by setting up the Baltic-Black-Aegean Seas (BBA) corridor.

The core question that underpins this infrastructural transformation project is whether the security emergency stemming from the situation in Ukraine has overtaken the primarily economic considerations that are supposed to guide infrastructure development. Apparently yes, in two ways.

First, in the short term, by fostering the infrastructural development for dual military-civil use due to the strategic situation on the EU/NATO’s eastern flank. This creates a form of economic profitability; however, its long-term viability is not guaranteed as it entirely depends on a given strategic situation that remains unpredictable.

Second, by the stimulation of long-term dynamics due to security and strategic urgency. Concretely, this means changing the whole infrastructural, economic and geopolitical rationale along the EU’s eastern flank. Accordingly, the strengthening of a North-South axis is determined by a geopolitical and strategic vision, not a purely economic one. In this context, funding is more readily available, as economic viability considerations are being complemented by strategic considerations in the funding process. For instance, despite years of Polish lobbying, it was not before December 2022 that components of the Via Carpatia – which connects Klaipeda (Lithuania) to Thessaloniki and Svilengrad (Bulgaria-Alexandroupolis junction) – were finally included in the TEN-T, which translates into substantial EU funding through the Connecting Europe Facility. However, the inescapable challenge will remain to vest these infrastructural projects with economic substance in order to make them viable on the long run and increase their resilience against geopolitical vagaries.

Alexandroupolis fits entirely in this picture. Indeed, it combines the two above-mentioned dimensions of the infrastructural reorganisation in the making along the Baltic-Aegean axis. Concretely, the key-infrastructure that will enable it to prosper beyond its role as military a hub is the railway. For instance, the first shipment to use a combined route (ship, rail) between Suez and Constanţa through Alexandroupolis was operated in 2020 at the port authorities’ initiative, a success they are particularly proud of. In addition, the Alexandroupolis-Ormenio/Svilengrad (Bulgarian border) rail link is being reactivated, with the construction of an electrified double line along the Greek-Turkish border. It is expected to be operational in 2028 at a cost of €1.078 billion and to improve Alexandroupolis’ connectivity and competitiveness. The fact that this funding comes from Greek public funds and not directly from the EU is interpreted by the port authorities as a strong sign of the Greek government’s commitment to the development of this rail line. And, indeed, Greece has diligently pushed for the development of an efficient rail connection with Bulgaria and Romania.

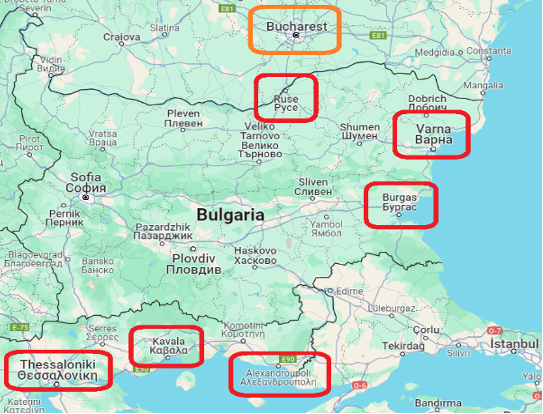

It is also worth evoking the “Sea2Sea” project between Bulgaria and Greece. It aims at connecting by rail the three northern Greek ports (Thessaloniki, Kavala, Alexandroupolis) to the three Bulgarian ports of Burgas, Varna and Ruse, the latter lying only 70 km from Bucharest.

The Greek and Bulgarian ports to be connected as part of the “Sea2Sea” project

Source: Screenshot for Google Maps, 2024; details added by the author

While the maturation of the Sea2Sea project was rather slow, the crystallisation of the geopolitical landscape along the EU/NATO’s eastern flank – reflected in the lasting distancing from Russia – seems to offer a more favourable context for its implementation. Accordingly, it was discussed at the two trilateral Greece-Bulgaria-Romania summits held in Varna in October 2023 and in Sofia in April 2024, as well as between the Greek Transportation Minister and the TEN-T coordinator.

Lastly, on the margins of the 2024 NATO summit in Washington, Greek, Bulgarian and Romanian defence ministers signed a Letter of Intent for the establishment of a Harmonized Military Mobility Corridor. It will connect Thessaloniki, Alexandroupolis, Varna and Constanţa (where the biggest NATO base in Europe is being built); it aims at facilitating the rapid movement of NATO troops in case of emergency. This supposes fluent connections and fewer transborder administrative obstacles. The first meeting to discuss the details of its implementation will be held in the fall of 2024 in Alexandroupolis.

These are concrete examples of how a challenging security and strategic context can initiate and boost the implementation of infrastructure projects.

Prospects and challenges

From the above, it becomes clear that the interlocking of multiple interests in Alexandroupolis and its region fulfils, at its level, several objectives. It enhances the Baltic-Aegean strategic, military, energy and economic corridor development. It serves the West’s attempt to integrate Ukraine and Moldova in its energy, economic and infrastructural system. It also satisfies part of Greece’s security needs in relation with Turkey and improves its positioning as an interface between Europe, the MENA region and the Indo-Pacific. Τhis creates significant opportunities for Greece to upgrade its geopolitical standing. Hence the suspension of the privatisation process of the port in 2022. This means the government intends to retain control on the port, whose development remains primarily a strategic issue that still needs to be managed at a high political level.

However, Alexandroupolis also faces outstanding challenges. On the one hand, the conflict in Ukraine – whose outcome remains uncertain – is critical for the future of the port, as attested by Greece’s repeated commitment to Ukraine’s security with regular reference to Alexandroupolis. On the other hand, much will depend also on Greece’s ability to expand and entrench its pivotal role on the arc extending from the Baltic to the Red Sea.

Alexandroupolis’ future as a military hub

A first challenge Alexandroupolis might be confronted with would be a substantial reduction of the flow of military personnel and equipment. This may happen if the Ukrainian conflict was to stall or even end, or if a US administration was to opt for disengagement. Yet, this is not necessarily the most likely scenario.

As pointed out by Michael Rubin, Alexandroupolis remains a valuable spot close to an increasingly challenging Black Sea, considering that the United States has not many completely safe harbours in the Eastern Mediterranean. Therefore, while the situation in Ukraine is crucial, Alexandroupolis is also part of a wider geopolitical configuration that diversifies its opportunities. The port authorities, for their part, also seem confident, claiming that a reduction of Western military aid to Ukraine will not necessarily lead to a substantial US military drawdown from Europe. They point out that even if the number of American units stagnates, their rotation alone generates considerable logistic needs. Therefore, if Alexandroupolis continues catching US military flows at the current rate (60 percent, according to the port authorities), it will remain critical. Accordingly, Greece will be able to continue ripping the benefits associated with this positioning.

Alexandroupolis and the economic dimension of the Ukrainian conflict

The economic dimension of the Ukrainian conflict has two main aspects: the grain export and the reconstruction.

Concerning the grain, the agreement allowing it to leave Ukraine-controlled ports and move through the Straits was suspended in 2023. While Ukraine’s rather unexpected ability to disturb Russian naval presence in the Black Sea has so far allowed the resumption of maritime flows, the overall security situation of the Black Sea remains highly challenging. On the long run, this requires the West to develop alternatives. In this context, the south-north land corridor that connects Alexandroupolis to Moldova and Ukraine may well be relevant for the West. Indeed, as Alexandroupolis’ connectivity with its northern hinterland is improving, Greece has steadily pushed for the transformation of the port into a hub for the Ukrainian grain on its way to the international market.

In this scenario, the cereals would use a route Russia cannot interfere with, unlike the maritime route. The strikes on Ukraine’s river ports of Izmail and Reni that followed the suspension of the agreement – and which eventually ended up in costing Moscow’s participation to the Danube Commission – suggest that an alternative to the Black Sea is realistic.

On their side, the port authorities of Alexandroupolis claimed to have foreseen the collapse of the grain agreement as early as in summer 2022 and exerted pressure on the EU Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (DG MOVE) to speed up the funding for the modernisation of regional road and rail infrastructure. They secured a €24 million budget under the European Commission’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, part of which will be allocated to the acquisition of high-speed grain loading infrastructure. According to the port authorities’ projections, Alexandroupolis could be able to handle part of the Ukrainian grain in one or two years. While several northern European ports are generally better equipped and already trade Ukrainian grain, Alexandroupolis offers the shortest land route between Ukraine and the Mediterranean Sea, and the shortest sea route between Europe, the MENA region and Asian countries, which are among the main recipients of Ukrainian grain. Therefore, once provided with the necessary infrastructure, Alexandroupolis can hope to become competitive in this field.

As far as Ukraine’s reconstruction is concerned, any projection is still premature since much will depend on the territorial reality that will emerge from the conflict, whenever it ends. However, a future reconstruction will generate colossal material needs given the task at hand. In this respect, Greece strives to create the conditions for its involvement in the reconstruction process, especially by using Alexandroupolis as a knot. Besides, along with grain exports, Ukraine’s reconstruction might well favour Greek shipowners, who control 25 percent of the bulk carriers’ world tonnage (80 percent at EU level) but express discontent with shipping being increasingly exposed to geopolitical contingencies and subject to unilateral restrictions perceived as unfair.

Conclusion: the way forward

While Alexandroupolis has managed to emerge as a strategic hub under specific geopolitical circumstances, the highly volatile geopolitical context may also challenge this dynamic. Accordingly, its future development relies on several conditions.

Firstly, the disconnection of the United States’ interest for Alexandroupolis from a potential reset of US-Turkey relations, as Turkey keeps being annoyed by the military use of the port and might well raise the issue in future negotiations. A certain decrease of the buzz on Alexandroupolis and the relativisation of its importance before the Turkish audience by US officials can be associated to the current thaw in US- (and Greece-) Turkey relations. Yet, there are few doubts in Washington that Ankara will remain a complicated and eventually undependable partner over the long run. Along with guaranteeing an elementary leverage on Turkish affairs, this requires for the United States to continue diversifying options. As Michael Rubin corroborates, the United States will keep on lessening reliance on Turkey regardless of any improvement in bilateral relations, since Ankara’s long-term commitment to the West is not guaranteed. In this context, he asserts, alternatives such as Alexandroupolis are not expected to be depreciated and the importance of the port meets bipartisan and trans-administration consensus in the US.

Secondly, Greece’s aptitude to build, operate and protect an efficient transport and energy infrastructure. 2023 was particularly tough for Greece’s infrastructure, especially for its railway network, part of which was paralysed for months due to unprecedently severe natural and man-made disasters. In addition, the whole – densely forested – region of Alexandroupolis was devastated by the largest wildfire ever recorded in the EU amid strong suspicions of arson. With transport and energy infrastructure becoming increasingly strategic and, accordingly, vulnerable to deliberate damage, Greece has to ensure the security and resilience of its infrastructure so as to cope with the responsibilities it is taking on. The increasing involvement of the intelligence and armed forces in dealing with such disasters, with particular focus on north-eastern Greece, suggests growing awareness on this issue.

Thirdly, the order that will prevail in the conflict-inviting area stretching from the Aegean to the Red Sea. Here, Greece’s interest is obvious, since the viability of the Baltic-Aegean axis also depends on the Eastern Mediterranean and Red Sea security to ensure fluent connection with the Indo-Pacific. Hence Greece’s commitment to Egypt’s stability, its leading role in the EU’s Red Sea naval mission ASPIDES, and its declared ambition to become India’s gateway to Europe as a link of the India – Middle East – Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). Yet, this supposes sustaining a collective engagement in this wide area, which is far from easy. Besides, Turkey’s posture remains a concern. Despite the current lull, Athens and Ankara still struggle to find a mutually acceptable strategic coexistence formula. Indeed, in a scenario that would dramatically increase its leverage on the EU, Turkey seeks to retain control on the connection of both the East-West Middle Corridor and the North-South maritime corridor with Europe. Hence its negative assessment of the IMEC and its poor alignment with EU foreign policy in critical transit areas such as the Eastern Mediterranean, the MENA region, the Red Sea and the Caucasus.

Last and most important, the further development of Alexandroupolis relies on the future of the Baltic-Aegean corridor and, accordingly, on the long-term prospects for Ukraine, Moldova, and Russian-European relations. All remain major unknowns to the day. Another critical element regarding this corridor is the stimulation of a strategic osmosis between Greece, Poland and the Baltic States, who are gaining weight in shaping Europe’s foreign and defence priorities. Greece’s recent accession to the Three Seas Initiative, the joint Greek-Polish proposal for a European air defence shield and other initiatives in the military field suggest a desire for greater engagement between Warsaw and Athens that may ultimately nurture a stronger common European strategic denominator between parts of Europe who have long shared very different priorities. France’s increasing military engagement in the Mediterranean-Baltic zone may also be interpreted through this lens, as both Greece and France are strong advocates of a European defence pillar – whatever the shape it may finally take.

Download (PDF)

Source link : https://www.frstrategie.org/en/publications/notes/port-alexandroupolis-strategic-and-geopolitical-assessment-2024

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-01 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.