The Parish Church of St Laurentius in Schann, Liechtenstein’s most populous municipality. Photograph by Kassie Borreson

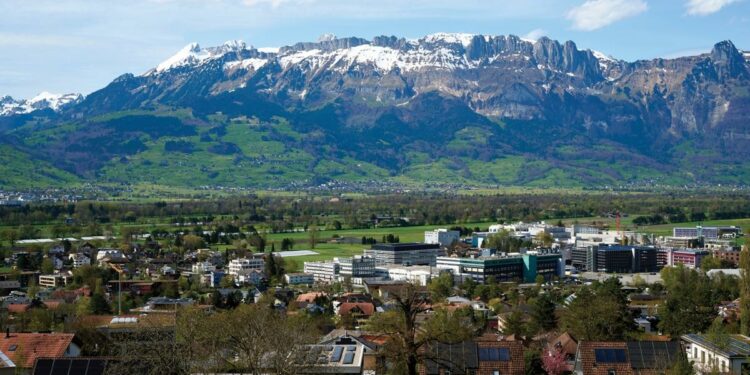

Tina lives on the eastern edge of Schaan, a six-minute drive north of Vaduz. With more than 6,000 residents, Schaan is Liechtenstein’s most populous municipality. Her stylish, modern, ground-floor flat, which she shares with her Swiss husband, Willi, stands on the plot her parents bought in 1948, the site of the small house in which she was born and raised. She and Willi met when she lived in Switzerland, and when they moved to Schaan, they built a three-storey apartment block with Tina’s nephews. Oliver lives with his wife and two small sons on the top floor, while Kevin, Laura’s younger brother, owns the flat in the middle.

Inside, I spot how spacious and light it is, but barely notice the gleaming kitchen, carefully chosen ornaments or her great-nephews’ art projects. I’m transfixed by the view: floor-to-ceiling, wall-to-wall glass doors frame a spectacular Alpine panorama of snowy peaks, forested slopes and verdant Rhine Valley.

Tina lays the shopping on the spotless kitchen island and ties on an apron painted with her great-nephews’ colourful handprints. She passes Laura a small knife and directs her to six apples and an old chopping board. It’s time to get to work.

Once a week, Tina’s family leave their respective workplaces in Schaan and Vaduz and at Lake Constance to gather here for lunch. “I don’t know why, it just started on Thursdays,” she shrugs. Today, she’s serving käsknöpfle — noodles layered with cheese, known in parts of other German-speaking countries as ‘spätzle’. While Laura starts on the accompanying apple sauce, her friend, Claudia, who was waiting outside in the sunshine when we returned from the shop, begins preparing the cheese. She grates a smooth, creamy yellow wedge of nutty Liechtensteiner würzig before unwrapping a pale, flattish log of sura käse, a tangy sour-milk cheese encased in a layer of translucent, jelly-like fat. “It has a very strong aroma, but you can’t smell it before it’s sliced,” Claudia says, and she cuts off the end. I lean closer; the white crumbly centre produces a slightly sour smell. “It’s an acquired taste,” remarks Tina. “My mum loved it, but dad said it wasn’t allowed in the fridge.”

Soon, Tina is making the batter for the käsknöpfle, carefully tipping a kilo of knöpfle (noodle) flour — a 50/50 blend of wheat flour and semolina — into a large stainless-steel bowl. She sprinkles in sea salt, then cracks 15 eggs on top, each one producing a little white puff of flour as it lands. Beating the ingredients together with a hand mixer, Tina breaks into Alemannic — a group of dialects spoken in southwestern German, Switzerland, Alsace and Liechtenstein — to deliver instructions to her sous chefs.

Willi and his niece, Laura, help to set the table for a meal of knöpfle. Photograph by Kassie Borreson

“Careful with your fingers!” she cautions Laura, who’s now slicing onions, before talking to me about Liechtenstein’s traditional food. “It’s simple stuff,” she says. “It came from what people had. Farmers had flour and eggs, so knöpfle was an economical meal.” And, she tells me, it’s the same with ribel, Liechtenstein’s national dish, made with cornmeal, milk and butter.

Tina and Willi cook all sorts of dishes together, but for the Thursday family lunches, Tina follows her mother’s traditional recipes, making the dishes she ate as a child. These include ribel, semolina dumplings in broth, shredded pancakes with plum and cinnamon compote, and sweet, yeasted dumplings with vanilla sauce. “That’s all the children want,” she smiles, Laura nodding eagerly in agreement. “They’re on rotation every six weeks.”

The käsknöpfle is one of Tina’s mum’s recipes, too. “This is how she always made it,” she says. Then, leaning over to inspect the sliced apples, which have been gently stewing with a cinnamon stick and splash of water, she describes the meals she and her four brothers and sisters grew up with. “We weren’t rich,” she says. “We ate lots of ribel, which is very nutritious, and rice pudding with milk and raspberry syrup. We had meat once a week.” Her parents grew fruit and vegetables to store and cook. “We had plums, nuts, an espalier [a supporting structure that allows a fruit tree to grow flat] at the front of the house for apples and pears. My parents grew a huge amount.”

Photograph by Kassie Borreson” data-src=”https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/uMegbvraHQ5P3kEKM2n9Vg–/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0MA–/https://media.zenfs.com/en/national_geographic_articles_149/b42a388ee2e209fce847ea10ae6caf7a”/>

For dinner, Tina’s family made käsknöpfle — noodles layered with cheese, known in parts of other German-speaking countries as ‘spätzle’. Photograph by Kassie Borreson

Outside in Tina’s neat, compact garden, her parents’ horticultural legacy lives on. She shows me her two raised beds, pointing out kohlrabi, lettuce and cauliflowers, and pots of kiwi, gooseberry and redcurrant plants growing beside them. Along the garden’s back border — the mountains in the distance, crisp and clear — there’s a row of espaliers for raspberries, apples, pears, almonds, apricots and plums.

Back inside, Tina brings a large pot of salted water to a simmer, rests a knöpfle scraper across the top and sets the bowl of thick, mustard-coloured knöpfle batter on the island alongside. “Look at the colour of it — it’s so yellow!” she exclaims. “It must be the egg yolks.” She scoops three ladlefuls into the knöpfle scraper, then rubs it vigorously back and forth so pieces of dough drop into the water below. Moments later, as dozens of wiggly little noodles rise to the top, Tina fishes them out with an old, slotted spoon that belonged to her mother. She gives the knöpfle a quick shake before spreading them out in a large white oval dish, which she then puts into the warming drawer beneath her oven. Tina and a rather nervous-looking Laura — it’s her first time making knöpfle — take turns repeating the process until the dough is used up, layering each batch of noodles with a generous scattering of cheese. Meanwhile, Tina fries the sliced onions in oil with a spoonful of flour to help them colour — “they’re important for flavour” — and once the käsknöpfle dish is full, she spoons them, brown and straggly, on top.

Willi and Kevin appear as Tina sets about cleaning her work surface. “I like to do that before eating,” she says. Kevin, an architect whose office is a four-minute walk away, has a tin containing an apple tart, which he sets down on the island. We head out to the patio to join Claudia and Laura, who’ve been busy setting the table. The vibrantly patterned tablecloth is laid with purple, red, yellow and green crystal wine glasses — soon to be filled with a delicately fruity grüner vetliner from the Prince of Liechtenstein’s winery — and rabbit-print napkins left over from Easter. There’s a whirl of activity and chatter as Willi serves the käsknöpfle and everyone helps themselves to toffee-coloured apple sauce and salad.

The apple tart recipe has been passed down in the family, with Kevin’s mother giving it to him and him sharing it with his mother-in-law. Photograph by Kassie Borreson

Once a week, Laura and her aunt Tina, along with the rest of their family, leave their respective workplaces to gather for lunch. Photograph by Kassie Borreson

I find myself distracted by the Alpine view again, and when I turn back to the table there’s a heap of cheesy, oniony noodles on my plate. The knöpfle are soft but chewy, the nutty, faintly sour mix of cheeses balanced by the unsweetened apple sauce. Bar the clattering of cutlery and the odd hum of pleasure, Tina’s family has fallen silent. “This is typical,” she laughs. “They all arrive and it’s very noisy. Then there’s food and it all goes quiet.”

I’m sitting opposite Kevin, who was just 19 when the communal house build began and who moved here from his parents’ home. I ask if he always comes over for Thursday lunch. “Of course,” he replies. “It’s a family tradition.” I’m taken by the thought of people all over Liechtenstein popping home from work for their midday meals. “Everyone in Liechtenstein can just go home,” he explains, “because it is so small.” Covering just 62sq miles, the principality is about the size of Washington, DC and is the fifth-smallest country in Europe.

Main course eaten, we carry our plates into the kitchen and watch as Willi slices the apple tart. He gently slides each piece onto a plate, adding scoops of sunny yellow vanilla ice cream alongside. Kevin made the tart to his mother’s recipe; she, in turn, had jotted it down from her mother-in-law. Its shortcrust pastry base is covered with flaked almonds and pieces of hazelnuts, then a layer of sliced apple and finished with a glaze of milk, cream, vanilla sugar and eggs. When I ask if he likes to cook, Kevin replies, “I like to, but rarely do it,” adding cheerfully, “I’m always invited to eat either upstairs or down.”

Tina spoons whipped cream onto the slices of tart and ice cream and we drift back out into the sunshine to eat it. The tart has a gentle flavour, barely sweet, the crunchy almond flakes providing a pleasing contrast to the soft apple and crumbly crust. The table is littered with cups of espresso and the warm, clear air is filled with the sound of forks scraping pastry off plates. I sit back and look at the view across the valley once more. I think I could be a mountain person, too.

Published in Issue 25 (autumn 2024) of Food by National Geographic Traveller (UK).

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6728a108225b427db62915bbe2bb8eea&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.yahoo.com%2Fnews%2Ffamily-meal-looks-liechtenstein-090000718.html&c=1428371862268750870&mkt=de-de

Author :

Publish date : 2024-11-04 01:34:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.