The Constitution of Bangladesh is astonishingly resilient. It has remained alive despite continuous attacks since it came into effect on 16 December 1972, marking the first anniversary of the country’s independence. Frequent assaults, such as two martial law regimes and numerous abrupt amendments, have drained its vitality.

Yet, it has survived, enduring for over five decades and surpassing the average lifespan of a constitution worldwide.

A debate now exists: does Bangladesh need a new constitution, as the current one may be too outdated to support a new Bangladesh, or should the existing constitution be reformed?

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard’s Google news channel

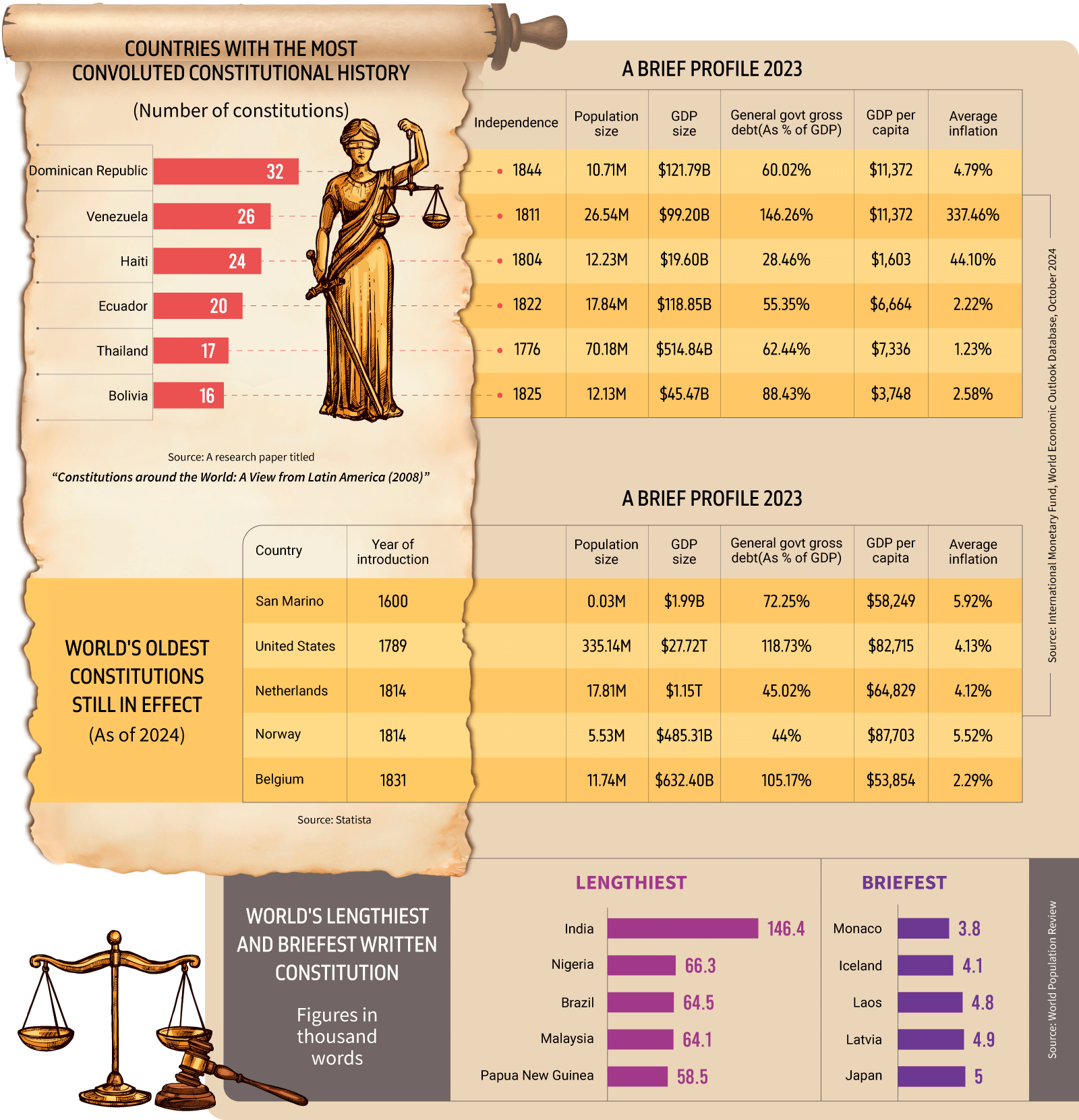

Various studies in recent years show that the average lifespan of a constitution since 1789 is between 17 to 19 years, much lower than the average life expectancy of the global population. Life expectancy at birth has notably increased worldwide. In 2024, the global average life expectancy is 73.33 years—less than half of what it was just two centuries ago. However, the average lifespan of a constitution, often called a “living document,” has not increased to the same extent over the last two centuries. Wars, internal conflicts, economic crises, and political unrest have shortened the lifespan of constitutions in many countries, leading to frequent renewals.

Consider some examples from constitutional history. The Dominican Republic holds the world record for the number of constitutions, having adopted 32 since its independence in 1844. This translates to a new constitution approximately every six years, far exceeding Thomas Jefferson’s idealistic notion that every generation should write its own constitution. Four other countries have had 20 or more constitutions, three of which are in Latin America: Venezuela, Haiti, and Ecuador. Thailand joined this group in 2017 with its 20th constitution.

However, there is another side to this phenomenon. San Marino, a small country, holds the record for the world’s oldest constitution, which came into effect on 8 October 1600. It is also the oldest constitutional republic on Earth. The current constitutions of the United States, Poland, Norway, and the Netherlands are among the oldest, with lifespans exceeding 200 years. Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Denmark, and Canada also have constitutions with lifespans of more than 150 years.

If the Magna Carta is considered a constitution, it would be the oldest in the world. Issued in June 1215, the Magna Carta was the first document to enshrine the principle that the king and his government were not above the law. It aimed to limit royal authority by establishing law as an independent power.

The length of a constitution varies significantly from country to country. India’s constitution is the longest written constitution in the world, with 146,385 words in its English version, whereas Monaco’s constitution, enacted in 1911, is the shortest written constitution, with 3,814 words. However, in terms of lifespan, the United States has the oldest and shortest constitution, containing 7,591 words, including its 27 amendments.

Illustration: Duniya Jahan/ TBS Creative

“>

Illustration: Duniya Jahan/ TBS Creative

Bangladesh’s constitution contains 27,600 words, while Pakistan’s constitution has more than double that number. On the other hand, some economies and societies do not even have codified constitutions, such as the United Kingdom in Europe, Hong Kong in Asia, and New Zealand in Oceania. Israel and Saudi Arabia are unique cases, as they do not have official written constitutions due to historical and religious reasons.

The constitutional histories of various countries offer valuable insights. The lifespan of a constitution often reflects the stability of a country and its democratic system. The longevity of a democratic constitution is also linked to economic prosperity, although France remains an exception.

Good political behaviour is the best remedy for a fragile democracy. Not only can it restore the health of democracy, but it also extends the lifespan of its constitution. Tragically, when political behaviour deteriorates, it often leads to the downfall of a constitution.

A Tale of Two Countries

The constitutional histories of the Dominican Republic and San Marino offer intriguing insights through their distinct characteristics.

The Latin American country, the Dominican Republic, holds the world record for the number of constitutions and has a history of political turbulence since its independence in 1844. Over the years, the country did not abandon democratic principles, but most of its governments, upon taking office, felt compelled to draft new constitutions that altered the rules to suit their own agendas. Many of its constitutions suffer from a lack of consensus on the rules governing national political life. During the 1960s, it was considered one of Latin America’s poorest countries. However, it has followed a path of growth over the last 50 years. The current GDP per capita in the Dominican Republic is $11,372. The average life expectancy for men is 69 years, and for women, it is 77 years.

In contrast, San Marino, which holds the world record for the oldest constitution, has a history of stability. The quality of life for citizens in San Marino is better than that of those in the Dominican Republic. People in San Marino enjoy high life expectancy, with men living to an average age of 85 years and women to 89 years. Its strong economy and infrastructure are believed to contribute to its long-lived citizens.

San Marino’s economy primarily relies on finance, industry, services, and tourism. It is one of the wealthiest countries in the world in terms of GDP per capita, which stands at nearly $58,000 in 2024, placing the country 17th in the world.

In terms of landmass and population, the Dominican Republic is much larger than San Marino. It has a population of 10.7 million and covers an area of 48,442 square kilometres, whereas San Marino has only 33,600 residents within a landmass of 61 square kilometres.

The governance systems have made the difference. Democratic institutions in San Marino are stronger than those in the Dominican Republic. When Napoleon invaded Italy in 1797, he respected the rights of San Marino, even though it is entirely surrounded by Italy. Napoleon admired San Marino’s leaders and promised to leave the country independent. Not only did he uphold this promise, but he also offered them more territory if they wanted it; however, San Marino’s leaders declined. The then-leaders were reported to have said, “wars end, but neighbours remain.” They understood that if they took the territory of their neighbours, they would likely face confrontations in the future.

In essence, San Marino escaped Napoleon’s wrath because he personally liked its leader. Napoleon also exempted San Marino’s citizens from all taxes and provided them with a large supply of wheat. He was, in essence, a devoted admirer of San Marino.

A Country Without a Constitution: Pakistan & Bangladesh Perspective

A constitution, the supreme rulebook for a state, outlines the fundamental principles by which the state is governed. It defines the primary institutions of the state and clarifies the relationships between these institutions—the executive, legislature, and judiciary. It limits the exercise of power and establishes the rights and duties of citizens.

The constitutional history of Bangladesh records numerous instances of turbulence. When it was part of Pakistan, known as East Pakistan, it experienced the abrogation of Pakistan’s constitution twice by military rulers.

Following its partition in 1947, Pakistan took nine years to draft its first constitution due to political instability. It took three governor generals, four prime ministers, and two constituent assemblies to produce Pakistan’s first constitution in 1956. However, that constitution lasted only two years after coming into effect in March 1956.

On 7 October 1958, then-President Iskandar Mirza staged a coup d’état. He abrogated the constitution, imposed martial law, and appointed General Muhammad Ayub Khan as Chief Martial Law Administrator. General Ayub Khan subsequently deposed Iskandar Mirza on 27 October that same year and assumed the presidency.

Four years later, a new constitution was adopted in 1962. However, it did not last long, as the country was once again placed under martial law. General Yahya Khan seized state power in March 1969 and abrogated the 1962 constitution, Pakistan’s second constitution.

For approximately two-thirds of its lifespan, Pakistan was without a constitution.

After gaining independence, Bangladesh endured two periods of martial law. During the first martial law regime, from 15 August 1975 to April 1979, the constitution lost its supremacy and was subordinated to martial law proclamations, orders, and regulations. The constitution was frequently amended through martial law proclamations.

The situation differed during the second martial law regime, which began with the overthrow of the then-elected government in March 1982. Military ruler General Ershad, who seized state power, declared himself Chief Martial Law Administrator and assumed all executive and legislative powers. He suspended the constitution for over two years, restoring parts of it only as needed. In November 1986, the constitution was fully reinstated.

Both martial law regimes sought to legitimise their rule by amending the constitution in 1979 and 1986, respectively—amendments known as the fifth and seventh amendments. In recent years, both amendments were declared illegal by the apex court.

Some other significant amendments, particularly the fourth amendment in 1975 and the 15th amendment in 2015, enacted by the governments led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Sheikh Hasina respectively, largely undermined the spirit of the original constitution.

How (Not) to Protect a Constitution

The historical context—two martial law regimes and subsequent abrogation of the constitution—prompted the framers of Pakistan’s third constitution to include a special provision aimed at ending extra-constitutional takeovers of state power.

The third constitution, created in 1973, included a special provision in Article 6 stating that any person who abrogates, subverts, suspends, or holds in abeyance, or attempts or conspires to do so, using force or any other unconstitutional means, shall be guilty of high treason. Under the High Treason (Punishment) Act, 1973, high treason is punishable by death or life imprisonment.

Despite this stringent provision, it did not prevent Generals Ziaul Haq and Pervez Musharraf from seizing state power, declaring martial law, and suspending the constitution in 1978 and 1999, respectively.

What Pakistan did in 1973, Bangladesh did in 2011.

In the fifth amendment case, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, in its full verdict released in 2010, strongly denounced martial law and the suspension of the constitution. “The perpetrators of such illegalities should also be suitably punished and condemned so that in future no adventurist, no usurper, would dare to defy the people, their Constitution, their Government, established by them with their consent,” observed the apex court, adding, “However, it is the Parliament which can make law in this regard. Let us bid farewell to all kinds of extra-constitutional adventures forever.”

Following this verdict, the Sheikh Hasina government included a special provision in the constitution through the 15th amendment in 2011, which also abolished the non-partisan election-time government to prevent the abrogation and suspension of the constitution.

This provision, introduced in Article 7A, prescribes punishment for the offence of abrogating or suspending the constitution. Article 7A states:

If any person, by show of force or use of force or by any other unconstitutional means—

(a) abrogates, repeals, or suspends or attempts or conspires to abrogate, repeal, or suspend this Constitution or any of its articles; or

(b) subverts or attempts or conspires to subvert the confidence, belief, or reliance of citizens in this Constitution or any of its articles,

then such an act shall be considered sedition, and the person shall be guilty of sedition.

If any person—

(a) abets or instigates any act mentioned in clause (1); or

(b) approves, condones, supports, or ratifies such an act,

then this act shall also be the same offence.

Any person accused of committing the offence mentioned in this article shall be sentenced with the highest punishment prescribed for other offences by existing laws.

The inclusion of this provision triggered widespread criticism, as legal experts argued that terms like “show of force” and “unconstitutional means” were overly broad and highly contestable. They argued that it provided an arbitrary scope that could encompass legitimate public discussions, debates, and even academic arguments about constitutional change under the term “unconstitutional means,” depending on interpretation.

Inside and outside of Parliament, then-Prime Minister Hasina strongly defended this provision. However, Hasina herself paid little heed to the spirit of the constitution. The 15th amendment, which also abolished the non-partisan caretaker government for elections, enabled her to stay in power during elections, which critics argue allowed her to manipulate the polls.

She retained power by holding three consecutive controversial elections in 2014, 2018, and 2024, undermining the constitution, which unequivocally supports democracy and human rights. Her approach to defending the constitution was based on rules that served only her interests. Article 7A could not save her, and in the face of a student-led public uprising, she hastily resigned, fled the country, and sought refuge in India. Her party, the Awami League, now faces the greatest crisis since its founding in 1949.

Does Bangladesh Need a New Constitution?

The interim government led by Mohammad Yunus has announced a nine-member Constitution Reform Commission, which is now working alongside several other commissions formed to reform the judiciary, police, electoral system, and public administration in efforts to build a democratic Bangladesh.

Several cases filed after the ouster of the Hasina regime remain pending with the Supreme Court, seeking the restoration of the non-partisan caretaker government abolished by the 15th amendment to the constitution in 2011, among other issues concerning judicial independence and the role of MPs.

Yet, the current situation remains puzzling. Student leaders who led the movement to oust the Hasina regime are demanding a new constitution, calling for the abrogation of the current one. The existing constitution, which is regarded as the product of a long struggle for freedom and the nine-month-long liberation war, is now being labelled by them as the source of Hasina’s authoritarianism.

It remains unclear, however, how it could be considered a source of authoritarianism.

The Constitution Reform Commission stated on Saturday that it would seek proposals from political parties and other stakeholders and then decide whether the constitution should be amended or rewritten.

Thus, the fate of the constitution now hangs in the balance.

France: The Fifth Republic

There is a popular joke about the French constitution: a man walks into a library and asks for a copy of the French constitution. “I’m sorry,” replies the librarian. “We don’t stock periodicals.”

France has had 16 constitutions since its first one in 1791, created after the French Revolution. It was drafted two years after the US Constitution, which has since become one of the oldest constitutions in the world.

The constitutional history of France reveals why, despite being one of the oldest nations on earth, it has had so many constitutions. Over the past two centuries, each new form of government in France has been accompanied by a founding text outlining the nation’s aspirations and principles. Thus, they have frequently opted for writing a new constitution.

The current constitution of the Fifth Republic was approved by referendum and promulgated on 4 October 1958.

Should Every Generation Write Its Own Constitution?

More than 235 years ago, Thomas Jefferson, a prominent advocate for democracy and the third president of the USA, proposed the idea, but it was ultimately rejected by James Madison, known as the father of the US Constitution.

Jefferson, while serving as minister to France, wrote an influential letter to Madison on 6 September 1789, passionately arguing in favour of the concept. He declared that the earth belongs to the living generation and that each generation should write its own constitution. “No society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law,” he wrote.

Using calculations based on Buffon’s demographic tables, Jefferson concluded that a generation lasted nineteen years. He reasoned that all contracts, constitutions, and debts should be voided, with new ones negotiated every nineteen years. No generation, he argued, should be burdened by the laws, agreements, or debts of the past.

James Madison, who later served as secretary of state under Jefferson’s government and succeeded him as the fourth president of the USA, rejected this utopian vision. He valued the stability of established institutions and laws as long as they respected the rights of minorities.

In response, Madison wrote a letter on 4 February 1790, complimenting his friend’s theory but dismantling Jefferson’s argument. In Madison’s view, chaos would ensue if all contracts, laws, and constitutions were arbitrarily voided after a fixed period. He also reminded Jefferson that many debts incurred by past generations were for the benefit of future ones.

Jefferson then set the subject aside and never raised it with Madison again.

The rest is history.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=6728df5868fe4d8cb8850ef29196efcc&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.tbsnews.net%2Fbangladesh%2Flaw-order%2Fwhat-if-every-generation-writes-its-own-constitution-984461&c=13851949277044608030&mkt=de-de

Author :

Publish date : 2024-11-04 06:50:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.