I’ve always wanted to see the Aurora Borealis, and when I mentioned to my husband Michael that I’d seen a good price on an October “Northern Lights” cruise up to northern Norway, he immediately perked up.

“That’s sounds fantastic!” he said. “Let’s do it.” Conveniently, we would already be on the same ship, on three previous itineraries.

There was, of course, no guarantee that we’d see the Northern Lights. But this was supposedly a really good year for the phenomenon, which results from solar wind interacting with the magnetosphere.

No, I don’t know what any of that means, but I can’t explain sunsets or rainbows either, and I still think they’re pretty, okay?

Anyway, to see the Northern Lights, the sky also needs to clear, and on the first three legs of our four back-to-back cruises, the weather in northern Europe had been surprisingly bad. Edinburgh had been so foggy that we’d never even reached the harbor.

Once our boat set out for Norway, the weather remained pretty dreary.

Then one night, Michael burst into the cabin. “The Captain just announced that the Northern Lights are visible right now!”

Excited, I followed Michael up to the crowded top deck, and people were definitely staring up at something.

But all I saw was darkness.

Michael took some photos, and with the increased exposure time of his camera, he captured some of the sky’s colors.

Hold on, I thought. Is this always the way people see the Northern Lights? Are the stunning colors you see in pictures just the result of an open aperture?

Were the Northern Lights all a big fat lie?

This is all we saw with the naked eye.

A few nights later, Michael gently woke me up in the middle of the night to say that the Captain had announced that the Northern Lights were visible again.

“And I think I know a better place to see them this time,” he added with a grin.

He led me to an almost deserted balcony in the ship’s bow. The sea and sky in front of us were almost pitch-black.

And this time, the Northern Lights were much clearer, even to the naked eye. The Northern Lights weren’t all a lie!

And I’d never seen anything like them: shimmering sheets of green and purple fluttering in the sky. At one point, I saw what looked like a cosmic waterfall gently spilling down from above.

On that second night, this is what it looked like to the naked eye. Subscribed

But they were less impressive than I’d seen in photos — dimmer.

“I think it’s still the light from the ship — it needs to be even darker,” Michael said. “But we’ll have better luck on our upcoming tour.”

I nodded. In Tromsø, our upcoming port 350 kilometers above the Arctic Circle, Michael had hired someone to take us far outside the city at night to get the best possible viewing of the Northern Lights.

But the morning we arrived in Tromsø, I woke up with a sharp ache in my lower back. I didn’t think too much about it at first. I figured I slept wrong, twisting a muscle.

Then I stood up and almost passed out from the pain.

Michael was elsewhere on the ship, but I immediately texted him that I needed help, and he quickly returned to the cabin.

“What is it?” he asked me, concerned.

“I need to go to the medical center,” I said.

Since I’m from America — a country with an insane health care system — I’ve long taught myself never to go to a hospital unless it is absolutely necessary, for fear of bankrupting us with sky-high emergency expenses. But there was no question in my mind that I now needed medical help.

It felt like I’d swallowed broken glass!

The next few minutes were a blur, and before long, I found myself on my back on a bed in the medical center, writhing in agony.

“It’s probably a kidney stone,” a nurse said as she hooked me up to an IV drip. She nodded to one of the liquid concoctions being added to the IV. “This is paracetamol for the pain.”

I tried to be patient, waiting for relief, but the painkiller never seemed to kick in. The pain was getting worse by the minute.

Michael saw the agony on my face.

“He needs something stronger!” he called to the nurse, but the center was really busy, and everyone was momentarily occupied.

It felt like an eternity before the nurse finally returned and added something else to my IV drip.

“What’s that?” Michael asked.

“Morphine,” she said.

Oh, thank God.

“How long before it takes effect?” I asked.

“Fifteen to thirty minutes,” she said.

Was this a joke? I couldn’t possibly survive another fifteen minutes of this pain!

As I drifted in and out of consciousness, I heard voices in the other room.

“The police are here to see the body.”

Somebody had died? I thought.

Part of me wondered — for literally the first time in my life — if maybe it wouldn’t be so bad to be dead. At least the pain would stop.

The doctor arrived, and I heard Michael talking about an ambulance, making arrangements to take me to the local hospital. It went without saying that I needed to go.

Nonetheless, I said, “No, wait! I don’t need an ambulance. We can take a cab.” Even then, I was thinking like an American, terrified by an additional $5000+ bill that our insurance would somehow wrangle out of paying. Maybe the painkillers were finally working a bit too.

Then I stood, and the pain roared back — stronger than ever, painkillers be damned. It seemed to be coming in waves, getting worse each time. If it was this bad with painkillers, what would it have been like without them?

“Hold on!” Michael was saying to the staff. “We need that ambulance after all.’“

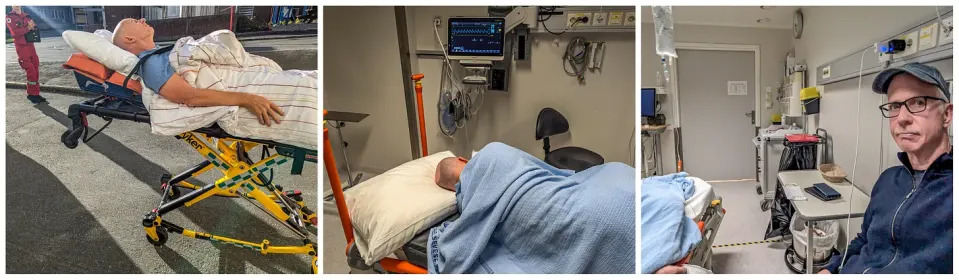

Then suddenly, there were paramedics around me, and I was on a gurney being guided out of the ship, down a ramp, across the parking lot to an ambulance waiting nearby. The pain was worse than ever, like I’d swallowed glass and my insides were now being twisted. The paramedics quickly added fentanyl to my IV drip.

“Another?” the paramedic asked me, and I quickly assented to a second hit.

But by the time we reached the hospital, the pain was only worse, so the doctor gave me a big shot of more painkillers — something that supposedly worked well on the pain of kidney stones. I was still getting regular infusions of morphine too.

None of this seemed to make any difference.

Me in bad shape — and Michael looking concerned.

The doctor said that ordinarily, a stone soon passes out of the kidney, and the pain ends. But I wasn’t getting any relief, and the doctor wondered if the stone was too big to pass on its own. So after a couple of hours of waiting in the emergency room, I was sent to the main hospital for a CT scan and a more thorough examination.

The new doctor said I’d need to spend the night.

Which meant the ship was going to leave without us.

“It’s no big deal,” Michael said to me. “We’ll catch up with it if we can. If not, we’ll just fly back to the U.K.”

At this point, the pain was still really bad, still coming in waves. I also had nausea from all the morphine.

But my luck finally began to shift. We got word that the next port of call was canceled due to high winds, so the ship would stay in Tromsø for three full days.

In all my decades of cruise ship sailing, I’ve never heard of a boat changing its schedule to stay in any port for three days.

Then I got the results of my CT scan, which was more good news: I had a kidney stone, but it was small-ish, only two millimeters, and it was almost out of the kidney and into the bladder. Once it was finally out, the pain would end, and it would just be a question of drinking enough liquids to flush out on its own through the urethra.

I was still drowning in an ocean of pain.

But whenever I came up for air, Michael would be right beside me, holding onto me, making sure I never got swept completely out to sea.

They wouldn’t let him sleep with me in my room, so he eventually returned to the ship for the night.

I was on four different kinds of painkillers now — getting regular infusions of at least two of them — but I’m pretty sure what had finally eased my torment was the damn kidney stone finally leaving my kidney, holing up in my bladder for the time being.

Michael returned early the following day with treats and videos, and I was finally starting to feel like myself again. I had no interest in food, so it was now just a question of drinking lots of water and monitoring myself, waiting for the kidney stone to leave my body.

It occurred to me that, health-wise, Michael and I had both had a really tough year — me having my “medical tourism” in Istanbul in April and Michael slipping and hitting his head at that pool in Oslo just two months earlier.

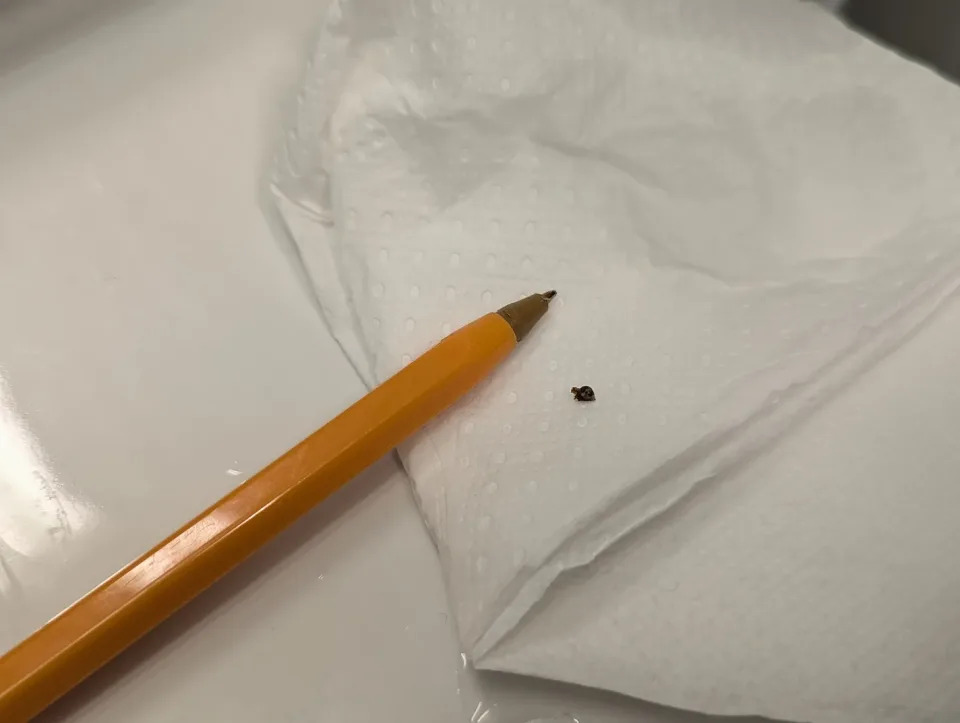

He had to leave again that night — and shortly after he did, the kidney stone finally made an appearance.

On one hand, it looked frighteningly small, especially for the amount of pain it had caused. On the other hand, just seeing it made me wince, imagining how it had slowly inched its way through a series of impossibly narrow tubes inside my body.

It looked small but loomed very large in my mind.

The next day, the doctors released me, and Michael and I headed back to the ship. Once on the boat, we couldn’t help but ask some acquaintances how that late-night Northern Lights tour had gone.

“It was incredible!” one said. “So much clearer than from on board.”

I knew Michael had really wanted to see the Northern Lights, and I felt terrible I’d made him miss it.

“Don’t be silly,” he said. “It’s not like it was your fault.”

A few days after we set sail, the Captain made yet another late-night announcement about the Northern Lights. But Michael and I were so exhausted from our ordeal at the hospital that we both slept through it.

“They were amazing,” a woman told us the following day. “I’ve never seen anything like them — so much better than those two times before.”

Then the news started reporting how conditions were so good for the Northern Lights that people were seeing them much farther south — even in the U.S.

Talk about rubbing it in our faces!

I felt stupid. We’d come all this way but barely seen the Northern Lights. Plus, for the first time in my life, I could feel my kidney — sore inside my abdomen.

But Michael smiled. “Don’t you realize how lucky we were? We got great medical care in Norway, and the ship didn’t leave us behind. If what happened to you had to happen, it couldn’t have gone any better — Northern Lights or not.”

He wasn’t wrong.

That’s when I realized I’d witnessed something beautiful after all.

It was Michael, who’d been with me every step of the way, first guiding me to the best possible Northern Lights viewing, and then watching over me, keeping me safe when something had gone very wrong.

Irony alert! He’s my husband, so I hadn’t even had to go far above the Arctic Circle to see him.

Except, in a way, maybe I did.

Pretty lights up in the sky? They’re impressive, and it would’ve been nice to get a better view.

But what I saw instead? I’ll take that over the Northern Lights any day.

On a canal in Bruges, Beglium, two weeks before my kidney stone.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67516a1849a34ebabfc6ee9ab04856d2&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.yahoo.com%2Flifestyle%2Fstory%2Fi-went-to-norway-to-see-the-northern-lights-i-ended-up-in-the-hospital-instead-074130200.html&c=16399509840836273105&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-12-04 23:42:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.