In a resolution drawn up this week, legislators in the European parliament said “both fresh EU funding for Georgian civil society and effective allocation of funding is more important than ever now that President Trump has frozen all such funding from the US”.

However, as in other areas of EU foreign policy, internal European divisions hinder a coherent response to events in Georgia. In particular, Hungary and Slovakia have blocked EU sanctions aimed at officials in the ruling Georgian Dream party.

Defending Europe’s interests

Among the various ideas for protecting and advancing Europe’s interests, I would like to pick out four proposals.

First, diplomacy. The British scholar Timothy Garton Ash suggests that Europeans must be hard-headed and co-operate more closely with non-European countries that may not share their democratic values:

See the world as it is, not as we wish it to be . . . ban all generalising waffle about “the global south” and view these countries as they do themselves: individual great and middling powers, with their own distinctive histories, cultures and national interests.

Second, military matters. In this editorial, the Brussels Institute for Geopolitics think-tank says:

Europe must be prepared to fend for and defend itself . . . It requires military capability and, critically, a separate command centre independent of Nato’s, so that if Europe is attacked, it has the means to defend itself operationally without the need to ask Trump for the keys.

Third, reform of the EU. Erik Nielsen, group chief economic adviser at UniCredit Bank, says:

I envisage a new “group of the willing” — maybe under the EU’s existing “enhanced co-operation” clause — of, say, the biggest five member states and open to the rest of Europe, covering a co-ordinated response to external economic coercion (whether from the US or China), diplomatic and defence relations.

Particularly, the UK would hopefully join in some capacity or other.

Finally, EU enlargement into eastern and south-eastern Europe. Stefania Benaglia writes for the Centre for European Policy Studies:

The EU must recalibrate its foreign policy with a strategic emphasis on enlargement policy, defence strategy and global partnerships …

A deadline must be set to sign the [entry treaties with candidate countries] because without it, the price will be the evaporation of European values across the wider Europe and an increase in Russia and China’s influence.

Europe’s internal divisions

The above proposals are sensible in many ways, but some will be harder than others to put into practice. A truly autonomous European military posture will not happen overnight — the decades-old reliance on the US defence industry is too high.

As for EU enlargement, it is desirable but, as I have written in the past, it faces obstacles — among them, the need for controversial reforms to the EU’s finances and decision-making processes; deep-seated historical disputes among existing and aspiring member states; and the lack of preparedness of most if not all countries that want to join.

Underlying everything is the inescapable fact of Europe’s internal divisions, both among governments and inside national political systems and societies.

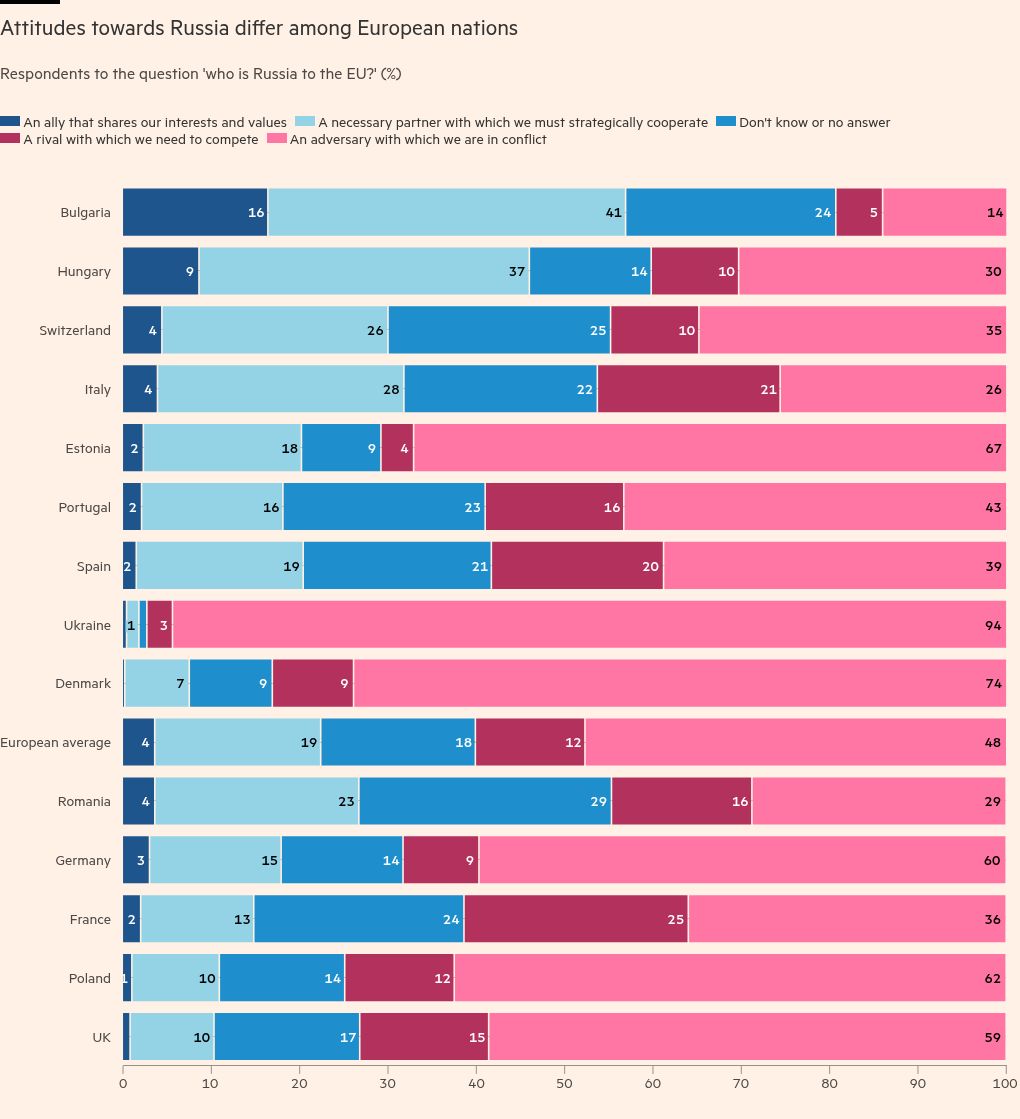

These are visible in European attitudes to the war in Ukraine and to relations with Russia, as indicated in a survey published this week by the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Disagreements have also been on full display during the war in Gaza, a conflict with serious consequences for Europe but over which it has exerted minimal influence.

Hard-right parties

European disunity is exacerbated by political and economic troubles in Germany — where elections will take place next weekend — and France, not to mention the rise of hard-right parties elsewhere that are either in government or exerting considerable pressure on policymaking from outside.

Paul Maurice of the French Institute of International Relations says:

“These situations create a leadership vacuum in key countries, complicating collective decision-making at EU level.”

Elusive unanimity in foreign policy

Is a united foreign policy unattainable in a loose confederation of 27 countries such as the EU? One of the most thoughtful discussions of this question appeared in a 2020 article by Josep Borrell, the EU’s former foreign policy chief.

He suggested that, on certain questions of foreign and security policy, the EU could relax its long-standing requirement for unanimity. But he added:

“I am clear that abandoning the unanimity rule would not be a silver bullet.”

A final point is whether the job once held by Borrell, and now by former Estonian premier Kaja Kallas, actually matters very much. Writing for the Responsible Statecraft site, Eldar Mamedov makes the trenchant but not unjustified observation:

“Despite its lofty title, the post has no real power.”

To sum up, the need for Europe to get its act together has never been more urgent, but external pressures and internal disputes give grounds for grave concern about the future.

By engaging with Syria’s new leadership, Europe could ease social strains in EU countries hosting refugees, diminish Russia’s influence in the Middle East and contribute to the region’s long-term security, Loqman Radpey writes for the Centre for European Policy Studies

Tony’s picks of the weekRecommended newsletters for you

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67b0945ea6eb44659f61fcc27c782dc9&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ft.com%2Fcontent%2F7c51e499-495e-4065-808c-85004c698c91&c=5432551207871228455&mkt=de-de

Author :

Publish date : 2025-02-15 03:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.