While the United States and most of the European Union have shrugged off the pandemic recession and restarted their economic engines, Germany remains idled.

Its economy shrank slightly in 2024, after adjusting for rising prices. Forecasts for this year don’t look much better.

And other measures look even worse. They show an economy rapidly sliding backward, stunning declines that have emerged as one of the biggest issues in the parliamentary election set for Sunday.

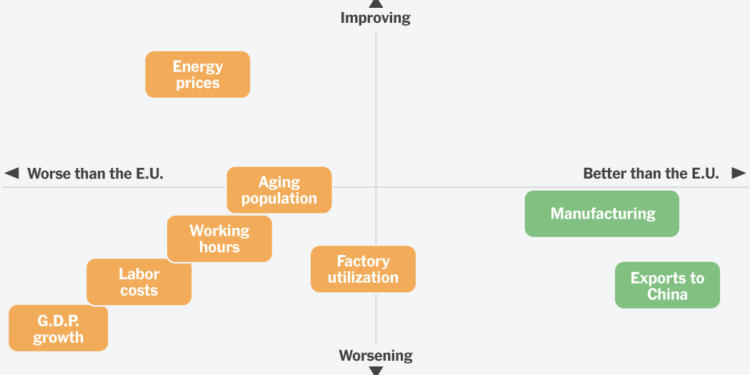

Source: Eurostat

Note: The horizontal axis shows the percentage difference between Germany and the total for the 27 countries in the European Union in the most recent data. The vertical axis shows how that metric has changed in Germany over the most recent 12 months of data. Both axes are plotted on a logarithmic scale.

The situation is nothing short of a national crisis. A country that has long prided itself on its work ethic and its manufacturing might is now watching global rivals race past it.

“Economic policy in Germany is in tatters,” Stefan Pallesch, a kitchen supply store owner from the nation’s wine region said this month on the sidelines of a political rally in the town of Stromberg. He went on to list several industries in crisis, including construction, traditional automaking, and electric vehicles.

Business leaders and many worried voters use the same word when describing what’s gone wrong: competitiveness. They feel as if they are a soccer star who suddenly can’t find the net, or a marathoner who can’t keep up with the lead group. And they feel like it’s happened almost overnight.

“I definitely believe that we can compete,” said Christian Klein, the C.E.O. of German-based software giant SAP, “but some fundamentals have to change.”

The charts below show just what it looks like when an economy rapidly loses its edge. They tell a stark story of industrial woe and workforce challenges, with few opportunities for a near-term turnaround of the sort German politicians are promising as they vie for the chancellorship.

‘Stuck in stagnation’

In the big picture, it’s impossible to miss Germany’s struggles. Start with growth, which helped make Germany the world’s third-largest economy but has only cracked 2 percent per year once since 2017. After adjusting for rising prices, the German economy is no larger today than it was five years ago. Government forecasters predict an anemic 0.3 percent growth rate this year.

Germany’s economic growth has stagnated.

Higher than the E.U. Lower than the E.U.

–10 –5 0 5 10 pct. pts. 15 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows year-on-year economic growth, adjusted for inflation.

“Germany is stuck in stagnation,” the economic minister, Robert Habeck, said late last month.

That’s partly because German leaders made a big bet on globalization that has not yet paid off. Even with a large consumer base at home, German companies rely on foreign markets for sales growth. More than four-fifths of the German economy depends upon trade, compared to about a quarter of the American economy. The threat of a global trade war, spurred by tariffs from the Trump administration, looms over everything.

The market that once looked most promising, China, increasingly looks fraught. German exports to China peaked in 2022 and have been declining, even though China is growing. That has drained fuel for growth. German companies have not yet found other markets to replace their slowing Chinese sales.

Germany exports more to China compared to other E.U. economies, but exports are declining.

Higher share of G.D.P. from exports to China

0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 % 3.0 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows exports to China as a share of G.D.P.

High costs, low demand

Much of Germany’s economic identity is wrapped up in its factories: cars, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, even espresso makers. That makes the sector’s struggles all the more painful.

Manufacturing is still the backbone of the economy, but it is declining.

Higher share of G.D.P. from manufacturing than the E.U.

14 15 16 17 18 19 % 20 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows the share of G.D.P. contributed by the manufacturing sector.

Manufacturing is falling as a driver of Germany’s economy. While German factories used to be the envy of Europe, they aren’t anymore. They’re not even above-average, in terms of output.

After decades of German manufacturing humming at much higher rates than its European counterparts, Germany idled more of its production lines last year than the European Union as a whole.

Germany’s factories have more idle capacity, and are now falling behind Europe’s.

Less idle capacity than the E.U. More idle capacity than the E.U.

70 75 80 85 % 90 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows industrial capacity utilization.

Factory owners, executives and workers all name the same culprit for that slide: soaring energy costs. It takes a lot of power to run a factory, and Germans pay more for it than their neighbors do. German politicians pushed the country before the pandemic to shutter its nuclear power plants and ramp up imports of natural gas from Russia. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the flow of gas stopped and energy costs soared.

Germany’s energy costs remain high, though are easing.

Cheaper than the E.U. More expensive than the E.U.

0.05 0.10 0.15 €0.20 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows the price per kilowatt-hour for consumers using between 70,000 MWh and 149,999 MWh, excluding taxes and levies.

The country has rapidly invested in renewable sources like wind and solar, but the country’s high energy costs remain a huge burden on companies trying to compete with rivals in Europe, Asia and America, where electricity costs less.

A less competitive workforce

Along with high energy costs, economists and business leaders complain that characteristics of Germany’s labor pool put it at a disadvantage. German workers are more expensive than their counterparts across Europe, largely because hourly wages are significantly higher than in peer countries.

Germany’s labor costs are high, and still rising.

Higher than the E.U.

20 25 30 35 €40 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows the cost of employing a worker, including compensation of employees, taxes, and subsidies.

And as a whole, its population works less.

Germans work less per week than those in the E.U., and their hours are still falling.

Lower working hours than the E.U.

35 36 37 38 hours per week 39 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows the average number of hours worked per week by full-time employees.

The country has also experienced shifts in worker preferences, often influenced by government policies.

In 1991, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, about 14 percent of Germans worked part-time. That number has more than doubled, to 30 percent.

Even full-time workers are logging fewer hours. And Germany has seen a surge in the number of days that workers call out sick, with an average of 22 recorded in 2023, according to the German Economic Institute.

Politicians across the political spectrum agree the country needs more workers, and will for decades to come. Germany’s post-war baby boom came later than America’s, and it is only beginning to see the wave of worker retirements from that generation.

Germany has more retirees per worker than the E.U.

Older than the E.U.

24 26 28 30 32 % 34 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 Germany E.U.

Note: Shows the number of people aged 65 or over as a percentage of the population aged 15 to 64.

Conservative politicians in the chancellor race have promised to curb government welfare payments to people who can work, but choose not to. Economists say the country’s policies, and its social norms, discourage women in particular from working more.

The workforce crisis would look even worse if not for the millions of refugees and other migrants Germany has taken in from countries like Syria, Afghanistan and Ukraine over the past decade. Economists say they’ve helped fill in the holes left by retirements and the shift to part-time work.

Last year, researchers at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in Paris reported that Germany had a 70 percent employment rate for immigrants in 2022. That was significantly higher than most other European Union countries.

The migration surge, though, has also strained German society and emerged as a top voting issue. Particularly in parts of the country where factory production has fallen, voters have embraced politicians who promise to block new refugees and deport those already there.

For some voters, it’s a complaint bound tightly to their experience of economic decline: the country, they say, no longer looks like the Germany they grew up in, and they want the old one back.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=67b8db4354824fc482dec238081f21d0&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nytimes.com%2Finteractive%2F2025%2F02%2F21%2Fworld%2Feurope%2Fgermany-economy-election.html&c=11914085960494833220&mkt=de-de

Author :

Publish date : 2025-02-21 02:10:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.