Secondly, our polling shows that voters distinguish between migrants from different countries – with much more positive views of those that they feel they know best, and whom they feel are culturally closer. For example, as we noted in a previous paper, Europeans tend to see the arrival of people from other member states and Ukraine in a more positive light than they do migrants from the Middle East or Africa. (Some of Ukraine’s immediate neighbours are a worrisome exception – especially Poland, where 40 per cent of respondents said they see Ukrainian migrants as a “threat”.) This leads us to believe that much of the public is less concerned with closing the borders – and more about having the ability to control the number of people who arrive and the right to choose who is welcome.

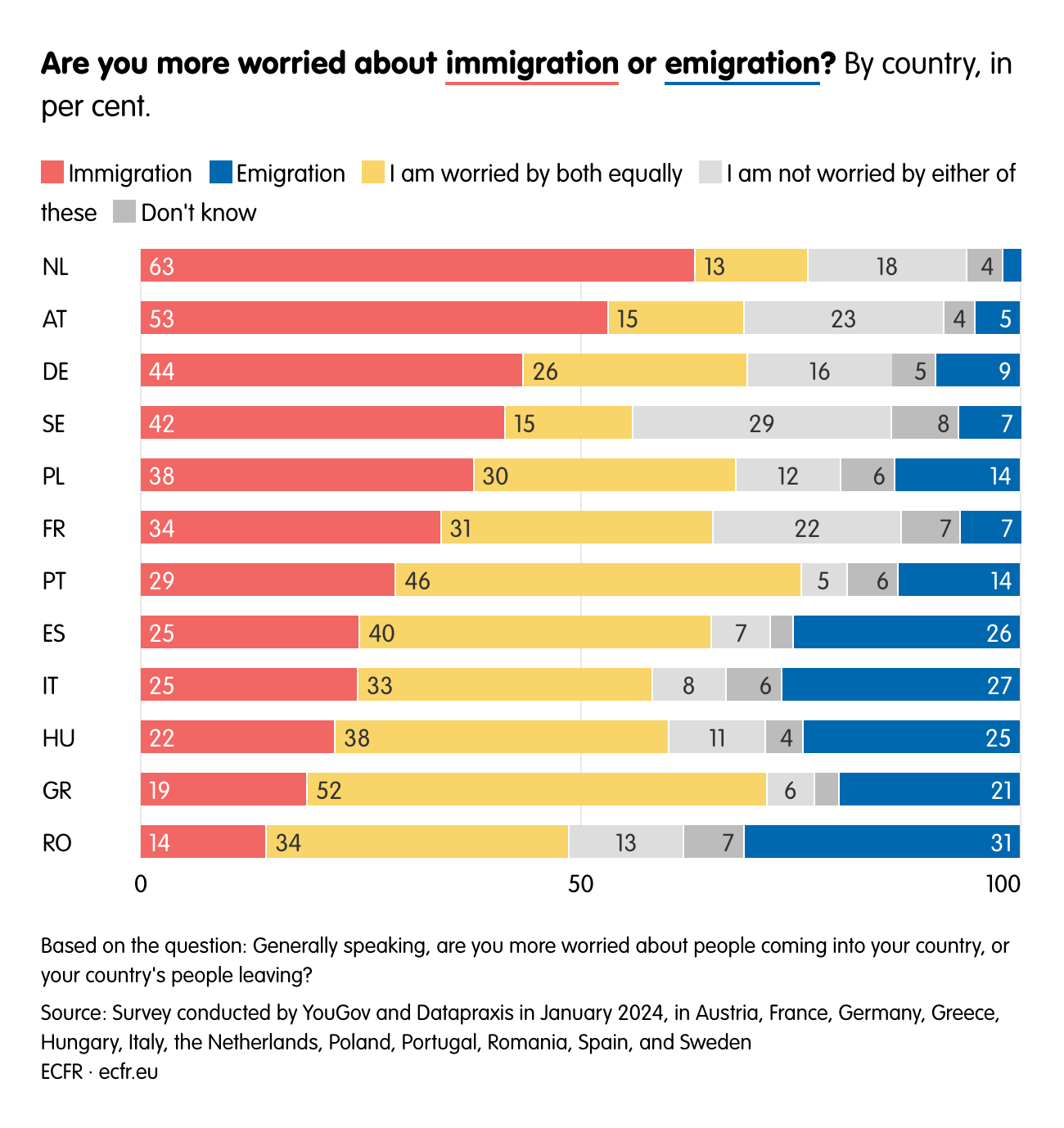

Thirdly, our polling found that concern about migration is not necessarily limited to immigration (people coming). A large number of European voters are more or equally worried about emigration (people leaving) from their countries than they are about the arrival of newcomers. On average, across the 12 countries polled, 34 per cent said they were more worried about immigration, but 16 per cent said they were more worried about emigration – and 31 per cent said they were worried by both equally.

Naturally, there are big variations across countries in this regard. Concern about immigration dominates in the wealthier countries and many of the older member states of the EU, such as the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, and Sweden. But Sweden and Austria also have large populations that are not concerned by either immigration or emigration. And in six countries (Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Spain), a majority is worried chiefly about emigration or about both equally.

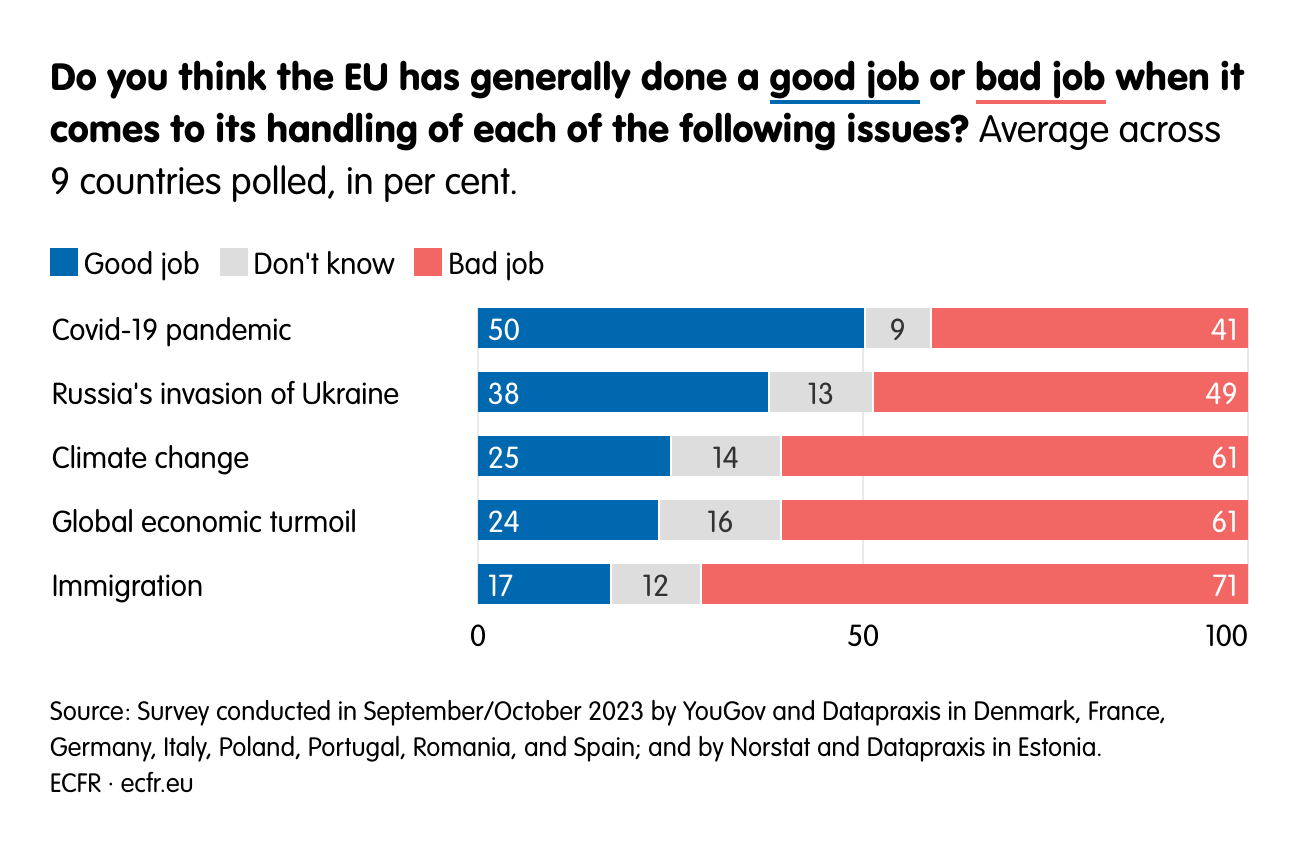

Our polling therefore suggests that the political centrality of immigration does not stem from the fact that it is Europe’s most acute crisis in the eyes of its inhabitants, but from right-wing parties’ success in making it a symbol of the EU’s failures. It is this crisis, alongside the economic crisis, that respondents to our earlier study thought the EU had responded the worst to.

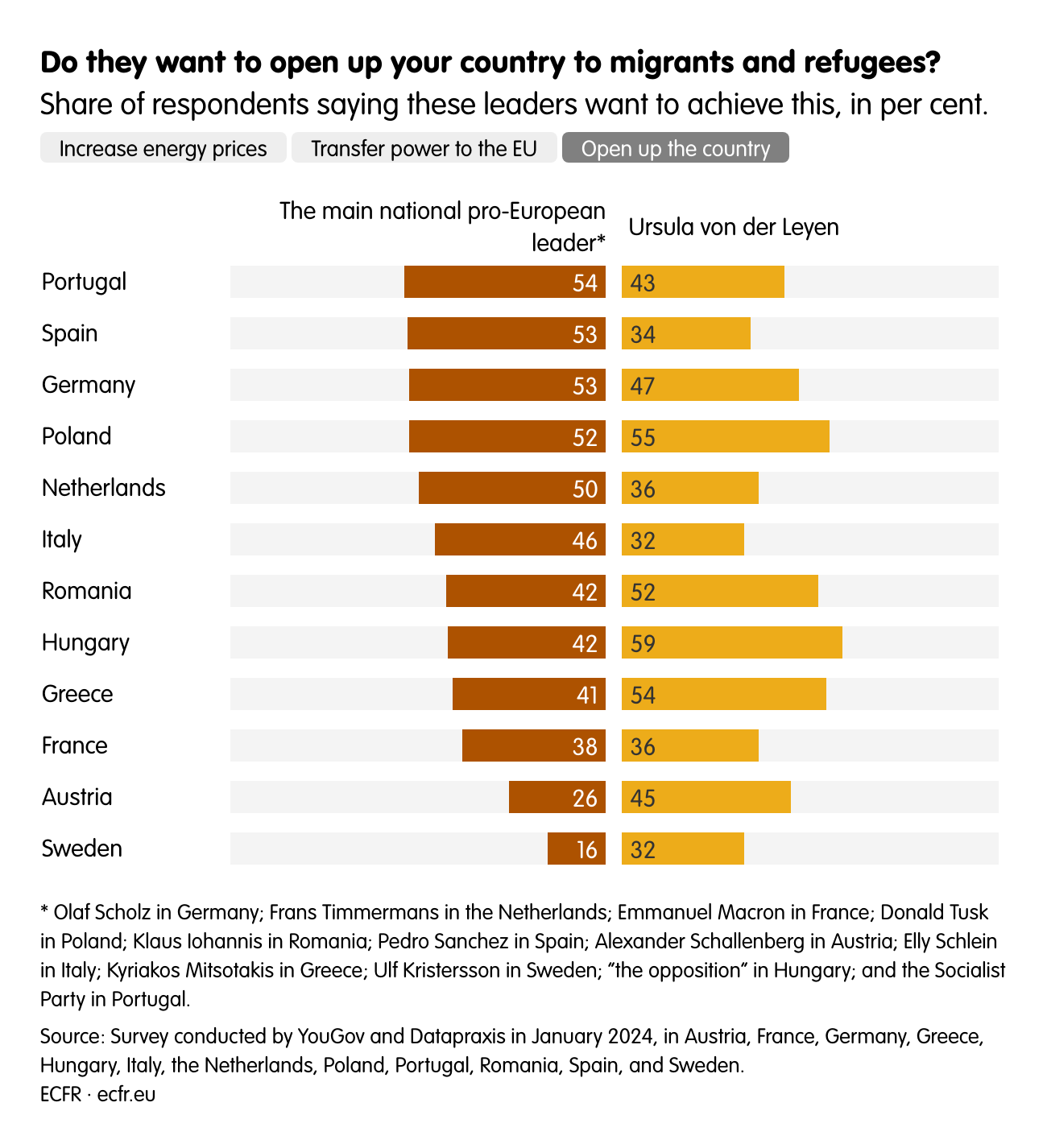

Most importantly, however, even those who are most concerned about migration are unlikely to believe mainstream parties that adopt far-right policies. The results of our polling show that despite what leaders say or do, voters suspect them of having ulterior motives – a phenomenon we refer to as “the rise of suspicious majorities”. When it comes to pro-European party leaders, a large number of voters suspect that, despite what they may say or do in public, they actually want to open up their country to migrants and refugees. Unsurprisingly, such thinking is prevalent among the voters of anti-European parties – with 66 per cent of Law and Justice voters, 57 per cent of AfD voters, and 53 per cent of Vox voters saying this is a priority of Donald Tusk, Olaf Scholz, and Pedro Sanchez respectively. The same intention is also attributed to European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen by a majority of voters of the Law and Justice party (66 per cent), Fidesz (60 per cent), and the AfD (50 per cent). It is therefore hard to imagine that any far-right party voters could be attracted by the mainstream just because the latter tries to imitate the far right on immigration.

Some mainstream parties may be adopting tougher stances on immigration for a different purpose: to avoid forfeiting to the far right the part of their own voter base most concerned by migration. But this is also unlikely to work given that high numbers of the electorate at large suspect the pro-European leader in their country wants to open it up to migrants and refugees – ranging from 54 per cent for the Socialist Party in Portugal to 38 per cent for Emmanuel Macron in France. In two countries – Sweden and Austria – the government leaders, Ulf Kristersson and Karl Nehammer, have managed to build up reputations as guardians of their country’s borders. Just 16 per cent of Swedes and 26 per cent of Austrians think that their head of government wants to open up their country to migrants and refugees. But it is debatable whether this approach is helping to limit the appeal of the far right even in these countries, where the far-right Sweden Democrats and Freedom Party of Austria are prospering.

Following the far right’s policies on migration carries many risks and provides no guarantee of attracting or retaining voters most concerned with migration. Where mainstream parties such as the Danish Social Democrats have managed to push back against the far right, they found an angle on migration where they had credibility – namely the defence of the Danish social model. If voters do not believe the underlying motivations for a policy shift, they risk seeing it as inauthentic – and opting for the genuine far-right product rather than the copy.

The paradox of EU success

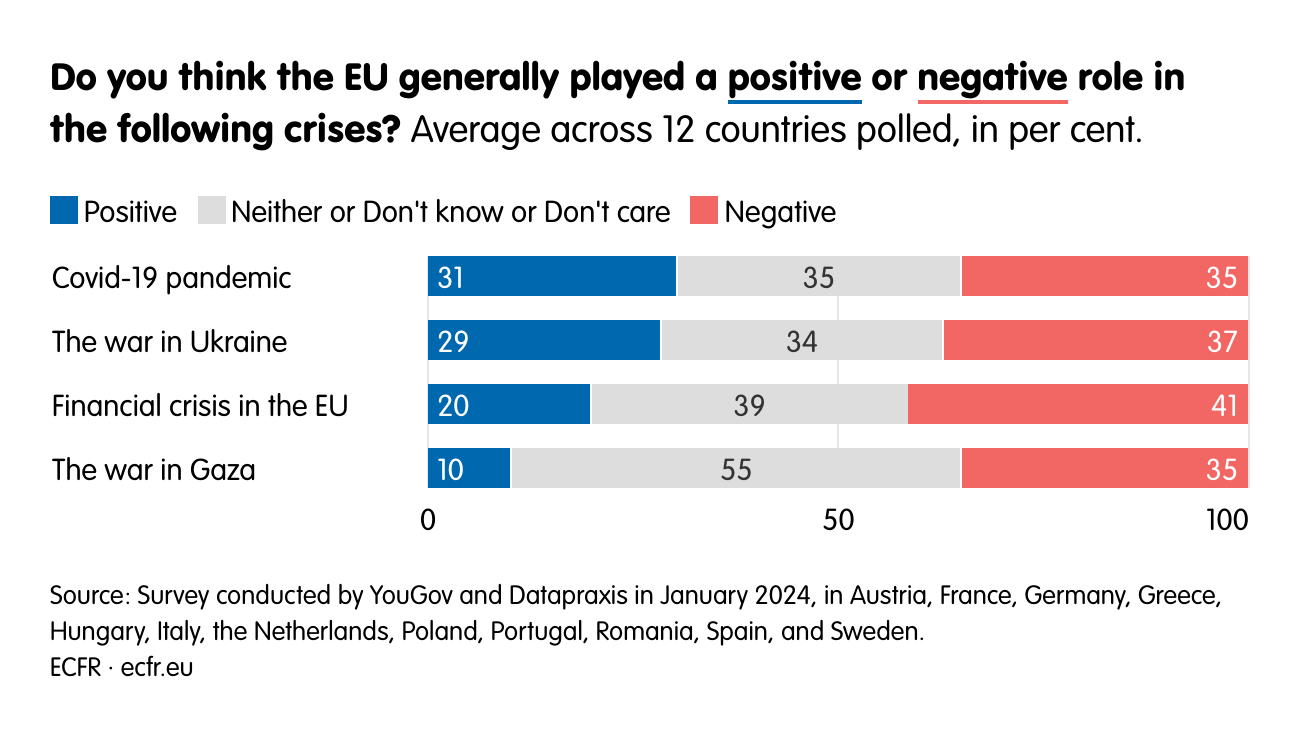

When it comes to talking about the other crises that Europe has faced in recent years, our polling reveals that mainstream parties risk emphasising precisely the things which are likely to make them unpopular. When pro-Europeans talk about what they see as the quintessential European success stories of the past few years – the response to the covid-19 pandemic, support for Ukraine, or the European Green Deal – they might actually be doubling down on their biggest potential weaknesses in the eyes of many voters.

This may be bewildering for European leaders who are, in many respects, rightly proud of the way they have dealt with the risks of covid-19, supporting Ukraine, and advancing the European Green Deal. But our data shows that few of these arguments will mobilise voters to their benefit. On the contrary, they risk creating more opposition than support.

The first reason for this is that many citizens see the EU’s performance in responding to several of the recent crises in predominantly negative terms. And while success has a short memory – people who may previously have seen the EU’s policy in these areas in positive terms now often take it for granted – the resentment of sceptics often has a longer life and has become an enduring part of political identities.

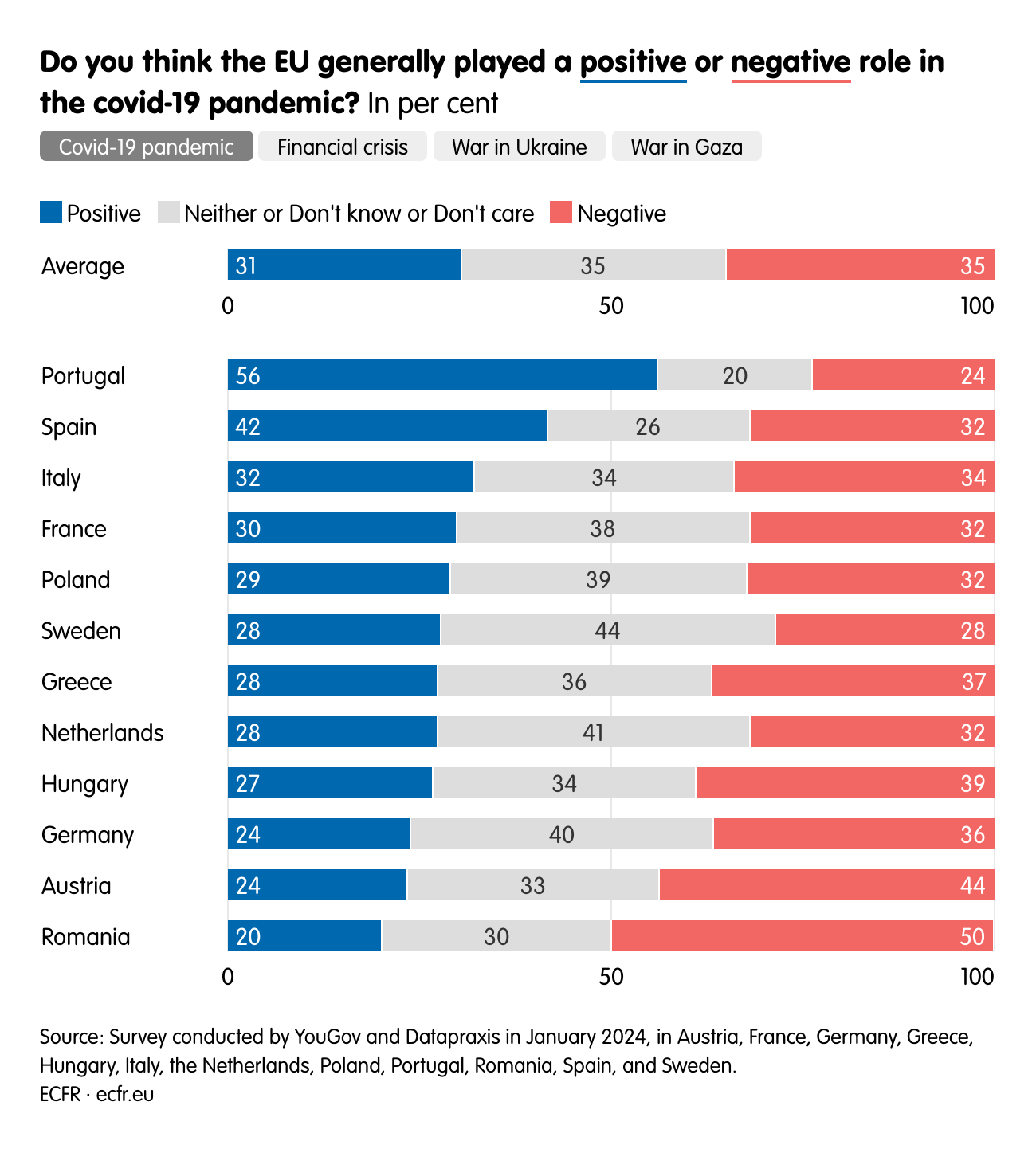

On covid-19, there is a significant gulf between the EU’s self-perception of having succeeded and the perception of much of the European public. Only in Portugal and Spain do more people think the EU played a more positive role than a negative one in responding to the covid-19 pandemic. We did not poll on national policies, but our sense is that the decisiveness of the governments – such as those in France, Austria, and the Netherlands – that pushed for lockdowns and obligatory vaccinations created a libertarian backlash.

This gulf in perception also extends to the other crises. Only in Sweden, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Poland do more people see the EU’s response to the war in Ukraine positively than negatively. And in none of the countries polled was the EU’s role in dealing with the financial crisis seen mostly positively. (In our previous survey, we also asked about the EU’s handling of the climate crisis and immigration, and discovered that in all nine member states polled, majorities considered the EU to have handled both crises poorly.)

The fact that – for the first time in EU history – the sitting president of the European Commission, von der Leyen, is running as the lead candidate of one of the political families, the European People’s Party, is a great opportunity for the pro-European majority to have a leader with strong popular legitimacy. But her candidacy also increases the temptation for mainstream parties to run their campaigns on communicating the EU’s successes. Our data suggests that this would be a mistake. Celebrating the EU’s successes could make these areas easy targets for far-right parties, whose electorates are particularly negative about the EU’s tackling of the different crises – and who might therefore end up mobilising more voters than pro-European parties.

And the problems run much deeper than that. Once again, voters’ perceptions of politicians do not just depend on their policies, but on the motives that voters attribute to them. As shown on the above graphic, across the board, many Europeans think that leaders of pro-European parties want not only to let migrants in but would also conspire to raise energy prices; some also believe they want to transfer their country’s political power to the EU. Most mainstream leaders are suspected of these motives, including von der Leyen.

Most importantly, such perceptions are not only widespread among far-right voters – but they are also, in several countries, non-negligeable among mainstream voters. For instance, 28 per cent of Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) voters in Germany think that Scholz wants, “above all”, to increase petrol and energy prices to help combat climate change. In Portugal and Spain, 24 per cent of the centre-right opposition’s voters think the same about their countries’ left-wing government leaders. Regarding the EU’s motives, 15 per cent of CDU/CSU voters also believe that von der Leyen – who comes, after all, from their political family – seeks, “above all”, to transfer power from Berlin to Brussels; with a further 28 per cent saying she wants to achieve this but not as a priority. The corresponding numbers for Germany’s Social Democrats (SPD) voters are also high, with 14 per cent believing this is von der Leyen’s priority and 36 per cent that it is one of her aims.

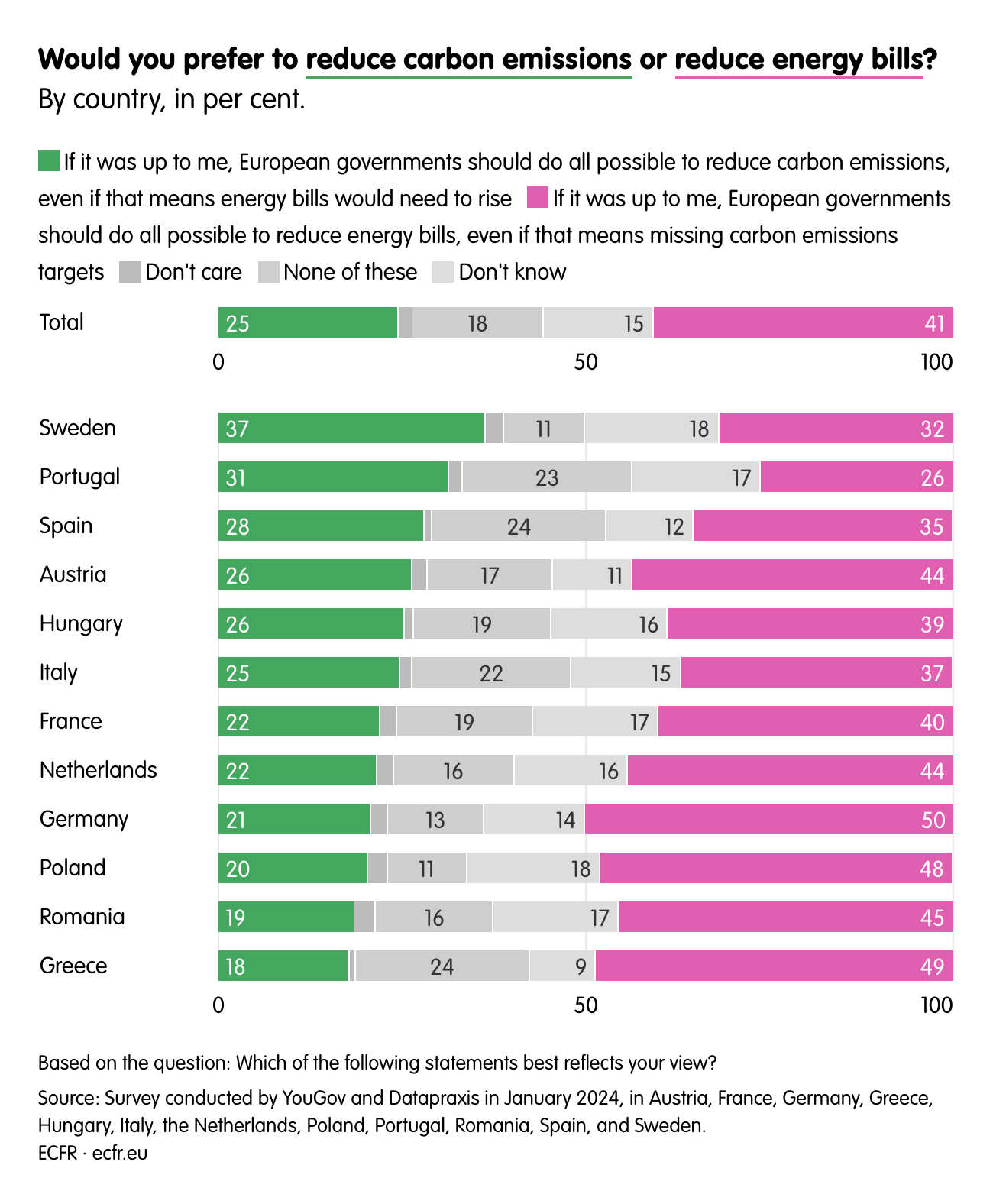

The EU’s climate policies are particularly divisive. In our survey, we asked people to confront a hypothetical trade-off between the two goals of pursuing climate ambitions and avoiding the rise of energy bills. In most countries polled – apart from Sweden and Portugal – more people preferred to reduce energy bills than privilege climate action. At the same time, however, in none of these countries did a majority select either of these two options. In each of them, a plurality – ranging from 18 per cent in Greece to 37 per cent in Sweden – opted for curbing carbon emissions. And usually only about a third chose neither of these two options, preferring to sit on the fence.

One powerful illustration of the danger of going big on EU priorities, such as the European Green Deal, in mainstream election campaigns is the backlash against green policies in Germany. After an attempt by the government to overhaul the country’s home heating systems proved exceptionally unpopular, the German Green party now wallows in the polls at a pitiable 13 per cent. German critics of climate policies do not tend to deny climate change, but they do challenge the pace of change. There seems to be an intensity gap between how Green party voters feel about climate change and how others feel.

From the electoral perspective, European leaders would also be wrong to over-emphasise Europe’s support for Ukraine in the run-up to the election. Plenty of people also see the EU’s response to Russia’s war in negative rather than positive terms. And there is a split (discussed in our previous paper) regarding the EU’s policy on the war between those who believe that Europe should support Ukraine in liberating all occupied territories and those that would rather push Ukraine towards negotiating a peace deal with Russia. On this, even fewer people (usually no more than 30 per cent) choose to sit on the fence. And in several countries – especially Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Spain – people are strongly divided between the two options. The key difference regarding the outcome of the war in Ukraine, compared to the climate issue, is that there are major geographical differences too – with support for Ukraine’s struggle to regain all of its territory prevailing clearly in Sweden, Portugal, and Poland, and the preference for a peace settlement dominating in Hungary, Greece, Italy, Romania, and Austria.

However, even where one option clearly prevails over the other, the issue of the war in Ukraine still has divisive potential. In Italy, Greece, and Austria, the current governments are supporting Ukraine to regain its territories against the dominant view among the domestic public. Meanwhile, in Poland and Sweden, where governments and the public broadly stand with Kyiv, elements of their Ukraine policy have prompted backlash, including against Ukrainian migrants and agricultural products – requiring leaders to choose their words about the war with utmost attention.

The rise of suspicious – or even paranoid – majorities means that elites can easily become the victims of their muscular rhetoric. European leaders risk focusing too much on policy while appearing removed from their electorates’ core concerns. If leaders want to stop the far-right’s rise, they will have to find a more authentic way of campaigning.

Four alternative strategies for mainstream parties

If pro-European politicians follow the conventional wisdom about the 2024 European Parliament election, they may end up accidentally mobilising anti-European forces rather than their own voters. But if mainstream parties are unlikely to prosper by aligning with the right on migration and speaking of the successes of the EU’s agenda, how can they push back against the surge of the far right?

Above all, they need to remember that the European Parliament election is primarily national in the way people vote. To minimise the triumph of the far right, mainstream parties therefore need to look for nationally specific ways of mobilising voters who support an outward-looking agenda while working to depress the results for the Eurosceptics. We see four main pathways towards such a strategy:

1. Making polarisation on the EU work for the mainstream

In the 2019 European Parliament election, pro-European parties effectively put the survival of the EU on the ballot. They managed to convince voters that far-right parties were seeking to leave the EU and follow in the footsteps of Brexit and Donald Trump. That will be much harder this time around – and it could end up helping Eurosceptic parties in many countries.

In countries like France and Italy, having a Brussels-centred strategy will likely backfire. The far-right parties in these countries have been busy de-risking themselves and abandoning pledges to leave the EU and the eurozone – so claims about saving Europe would not be credible. Moreover, these parties are likely to benefit from a campaign focused on Ukraine, covid-19, or climate change, which will disproportionately mobilise voters for anti-European parties. Neither a get out the vote campaign nor a generalised attempt at polarisation is therefore likely to benefit pro-European parties.

Although a generalised campaign to save the EU is unlikely to work, there is potential for an effective polarising strategy in countries where the far right is perceived as extreme outside of its own voting base.

This is particularly true of Germany where a large number of voters think that one of the AfD’s priorities is for Germany to leave the eurozone and the EU. The mass protests against the far right that took place across Germany earlier this year show that the threat of the AfD’s rise has a strong mobilising potential for the mainstream. There is also potential for such an approach in Poland, Austria, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands, where large parts of the population are worried that populists in their countries will want to leave the EU or eurozone, or see the EU break apart. In Poland, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Sweden, majorities of the voters that are supportive of parties other than the Law and Justice, PVV, AfD, FPÖ, or Sweden Democrats consider exiting the EU to be a priority agenda of their country’s main anti-European party.

Polarising the election around attitudes to the EU will not work in countries where the far right has polished its image, but may be successful in combatting parties that have a mainstream background but have turned to the right (such as the Law and Justice party or Fidesz).

2. Demobilising the Eurosceptics, mobilising the mainstream

Pro-European leaders have many reasons to be worried about the election. Europeans are exhausted by crises and a sizeable block of voters see the EU’s response to every one of the crises that has shaken the continent in the last 15 years as negative. Many of them are currently indicating their support for anti-European parties. But many of these people won’t necessarily vote. In fact, a large proportion of the people who express sympathy for anti-European parties might have not just given up on the EU – or on mainstream parties – but on politics altogether.

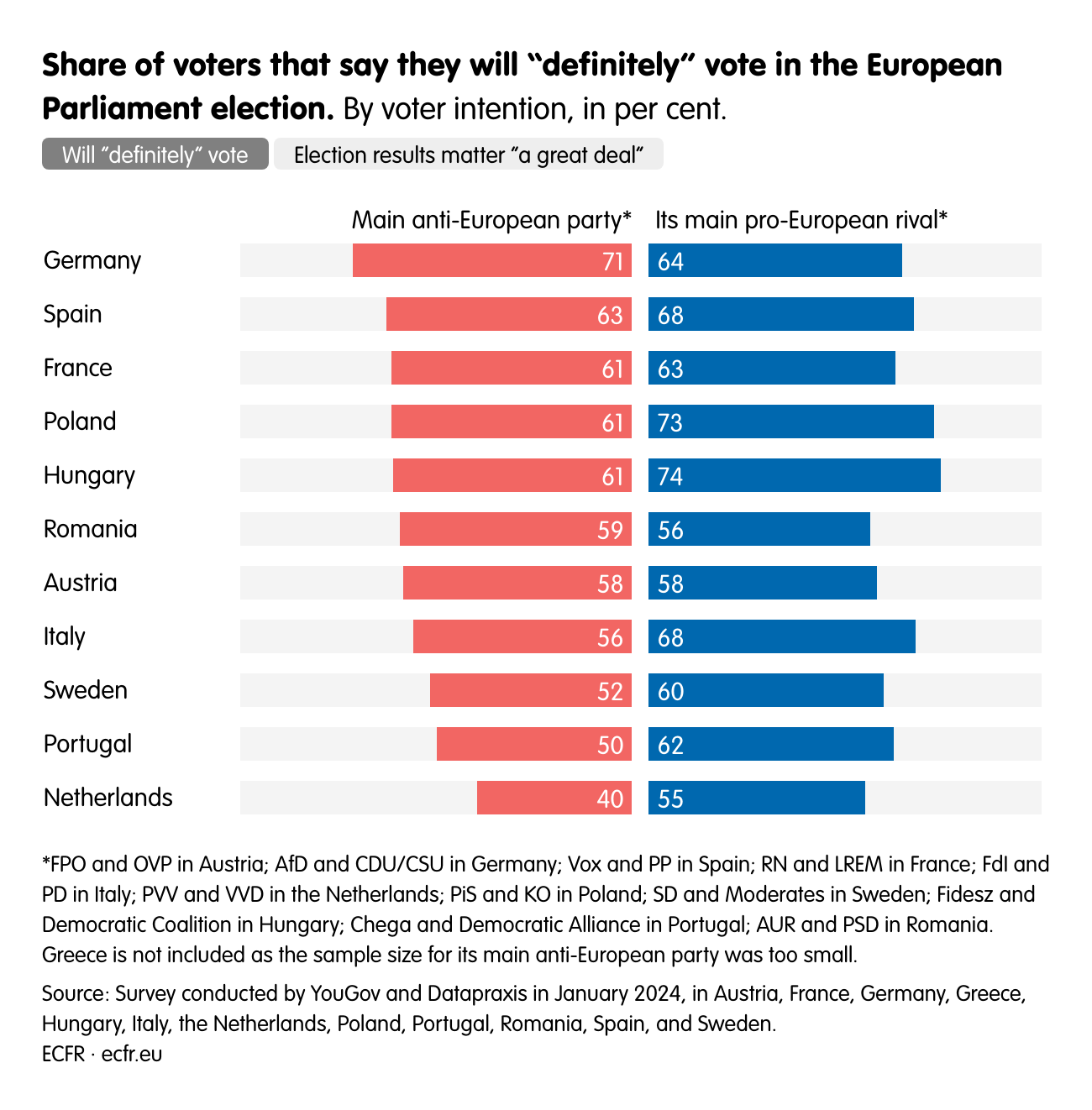

In the past, far-right voters used to be less likely to vote than supporters of the mainstream; after all, why would they bother to vote in an election that is about an institution that many of them would rather see abolished? In some countries (such as the Netherlands, Poland, and Sweden), voters of anti-European parties continue to be less mobilised than those of their pro-European rivals.

However, in some of the EU’s most influential states (such as Austria, France, and Germany), voters of anti-European parties are now highly mobilised – sometimes even more so than mainstream voters. AfD voters, for instance, are among the ten most mobilised party electorates from across the 12 countries polled; they are more likely to vote in the European Parliament election than CDU/CSU or SPD voters. In France, roughly as many La République en Marche (LREM) and National Rally voters say they will “definitely” vote – 63 per cent and 61 per cent respectively.

In these countries, therefore, the campaign will largely need to be about mobilisation. Pro-European parties need to work to mobilise their own voters – for example, by underlining the stakes of this election, stressing the risks of an asymmetrically high mobilisation among anti-Europeans for different issue areas (such as the EU’s environmental, social, and economic laws), or presenting the European Parliament election as a test of whether the far right could be stopped on a national level (which is a particularly relevant issue in Austria, France, Germany, and Spain, given the upcoming national elections).

But the mainstream also needs to look for ways to discourage voters of anti-European parties from voting for them. While it is unlikely that these voters would switch camps, they might not vote at all if not provoked to by an election that focuses on tropes that mobilise the far right such as immigration, or their perceptions of negative policies on covid-19, climate, and Ukraine.

3. Focusing on other crises to appeal to undecided voters

In some countries, pro-Europeans should look to push back against the migration obsession of the far-right parties to target undecided voters that have wider concerns.

For example, in France, the performance of Macron’s LREM largely depends on whether it can be successful in attracting the 24 per cent of voters who don’t yet know who to vote for in the European Parliament election. These people are obviously less mobilised – but not totally demobilised. Of them, 21 per cent say they will definitely vote, and a further 31 per cent say they will probably vote. Ten per cent of undecided voters see the election as mattering “a great deal” for their future, and a further 30 per cent say it matters “a fair amount”.

Most importantly, 37 per cent of them did not vote in the second round of the French presidential election in 2022 – but 44 per cent of those who did voted for Macron, compared to 19 per cent who voted for Le Pen. It is therefore a pool of people who have previously voted for Macron at least once.

In most countries, the undecided voters are overrepresented by women. They represent 75 per cent of the “don’t knows” in France, 73 per cent in Austria, 71 per cent in Spain, 69 per cent in Poland, and 66 per cent in Germany. Some of them might be attracted by parties that prove their interest and credibility in tackling the concerns that are common among women, for example around abortion laws, workplace equality, and minority rights. Poland set a promising example in this regard last year when a record mobilisation among women helped to vote out the conservative, Eurosceptic government.

4. Making the geopolitical case for Europe

The biggest challenge for pro-European parties may be to work out how to talk about geopolitics. One of the key strategic decisions that they need to make when preparing for their campaign is how much attention they should dedicate to the war in Ukraine – and what language to use when discussing it.

On the one hand, those most supportive of Kyiv would not want that war to become relegated to the second plane, as that would make it harder still to ensure continued financial and military support. But politically it would be dangerous for the mainstream if the war in Ukraine becomes a key battleground in the upcoming election. Many anti-European parties might then exploit the war fatigue among the European population. There is also a risk that profiling the far right as Vladimir Putin’s allies or facilitators could erode the broad anti-Putin consensus that has emerged since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Based on the results of our polling, we believe that turning the Ukraine war into a central focus of the campaign would backfire on pro-European parties. For one thing, only 10 per cent of Europeans polled think that Ukraine can win the war. Europeans also have mixed feelings about the EU’s performance in responding to the war and about the EU’s strategy going forward. Making Ukraine a central issue could bolster the opposition – and stoke fears about the threat to European agriculture, industry, and society in many member states.

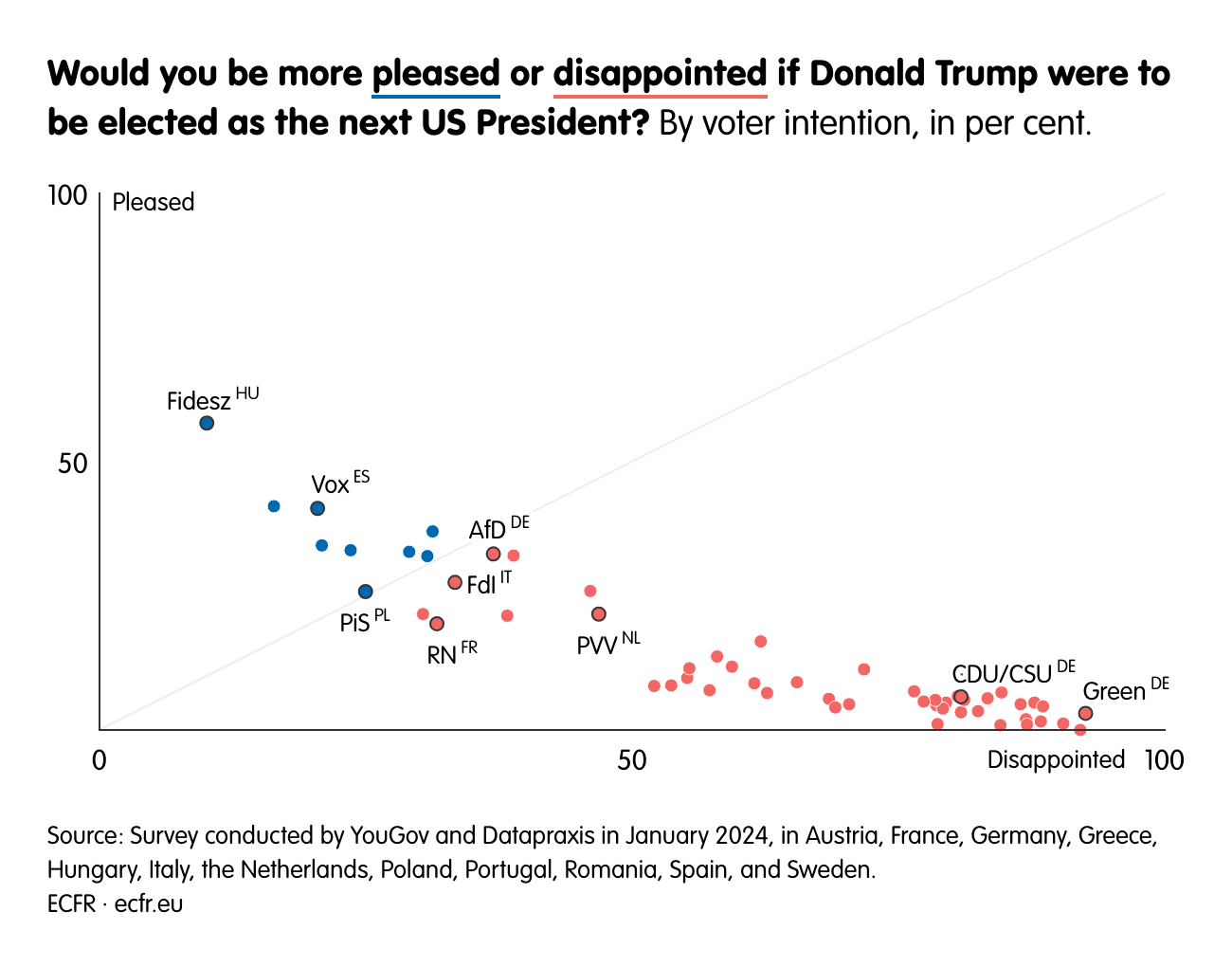

On the other hand, there is underexplored room for a geopolitical case for Europe in relation to Trump – about whom Europeans are much less ambivalent. As shown in our previous study, the vast majority of European voters will be disappointed if he wins the US election this autumn (Fidesz is the only party whose voters would be, in their majority, pleased by this result). And Europeans are particularly worried about him handing Putin a victory in Ukraine. The prospect of Trump winning could create an opening for some European leaders to focus on European sovereignty and to distance themselves from the US during the campaign. Rather than talking about the EU’s success in supporting Ukraine, pro-European leaders could frame the discussion around the need for the EU to become more autonomous and serious about defending itself from the Russian threat.

Ironically, the prospect of a second Trump presidency could wake European voters up to the importance of preserving a pro-European direction for the next European Parliament. When Trump throws the stability of the US security guarantee into question, Europeans should realise the importance of being able to rely on their fellow EU members and on EU structures. Contrary to the previous European Parliament election, in which several anti-European parties hoped to benefit from Trump’s electoral victory, this time Trump could mobilise pro-Europeans even before the result of the US election.

The uses of adversity

The crisis of European democracy – and the prospect of a far-right surge – are real, but the coming election does not need to see mainstream politics eclipsed by the far right.

Pro-European parties have a chance to end up in a much better position than many expect, and with a workable majority in the European Parliament. But in order for this to happen, European leaders need to part with some of the myths with which they are currently living. And they need to regain the initiative in setting the terms of the debate.

They should not make this an election about migration or about the successes of the last European Commission. And they should not choose between a polarisation or fragmentation strategy at the European level. Instead, they should adopt a set of differentiated national strategies like those described above to mobilise their supporters without provoking far-right voters.

This should include making a new geopolitical case for Europe, which does not attempt to mobilise people out of solidarity with Ukraine – but rather out of a concern for European sovereignty and security. Faced with uncertainty in American politics and Putin’s aggression, pro-Europeans should argue that we are in a moment in which if the EU did not exist, it would need to be invented.

Methodology

This report is based on a public opinion poll of adult populations (aged 18 and over) conducted in January 2024 in 12 European countries (Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden). The total number of respondents was 17,023.

The polls were conducted online by Datapraxis and YouGov in Austria (4-11 January, 1,111 respondents), France (2-19 January, 2,008), Germany (2-12 January, 2,001), Greece (8-15 January, 1,022), Hungary (4-15 January, 1,024), Italy (5-15 January, 2,010), the Netherlands (5-11 January, 1,125), Poland (2-16 January, 1,528), Portugal (3-15 January, 1,037), Romania (4-12 January, 1,030), Spain (2-12 January, 2,040), and Sweden (2-15 January, 1,087).

About the authors

Ivan Krastev is chair of the Centre for Liberal Strategies, Sofia, and a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences, Vienna. He is the author of “Is It Tomorrow Yet?: Paradoxes of the Pandemic”, among many other publications.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is the author of “The Age of Unpeace: How Connectivity Causes Conflict”. He also presents ECFR’s weekly “World in 30 Minutes” podcast.

Acknowledgments

This publication would not have been possible without the extraordinary work of ECFR’s Unlock team, particularly Pawel Zerka, who offered key analytical insights into the data and helped sharpen the authors’ arguments, as well as Gosia Piaskowska and Linda Hanxhari, who illuminated some of the most important trends. Flora Bell was a brilliant editor of various drafts and greatly improved the narrative flow of the text. Andreas Bock led on strategic media outreach, Nastassia Zenovich on visualising the data, while Anand Sundar navigated successive drafts. The authors also thank Paul Hilder and his team at Datapraxis for collaborating on developing and analysing the European polling referred to in the report. Despite these contributions, any mistakes remain the authors’ own.

ECFR partnered with Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation on this project.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.

Source link : https://ecfr.eu/publication/getting-the-european-parliament-election-right/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-03-21 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.