Introduction

Belarus’s complicity in Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine has tightened the bonds between Minsk and Moscow, and brought their lopsided alliance one step closer to full-fledged integration. President Aleksandr Lukashenko, Belarus’s longtime post-communist leader, has turned the country into what rights watchdog Freedom House terms a “consolidated authoritarian regime” and one of the world’s least democratic states. His growing alignment with Russian President Vladimir Putin bodes ill for the democratic and economic aspirations of the Belarusian people and raises grave new security concerns in Europe.

What’s the history of the Belarus-Russia relationship?

More From Our Experts

Like with many smaller European states, the land comprising modern-day Belarus has traded hands many times over the centuries, battled over by larger powers in the region, including Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, and their antecedents. Belarus largely took its current shape as the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, which composed part of the Soviet Union from 1920 to 1991.

More on:

Belarus

Russia

Ukraine

Military Operations

NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization)

Daily News Brief

A summary of global news developments with CFR analysis delivered to your inbox each morning. Weekdays.

Belarus’s close—but at times, quarrelsome—relationship with Russia is largely a legacy of their shared eastern Slavic ancestry and Soviet past, during which power was heavily concentrated in Moscow. Belarus hosted Soviet nuclear weapons and military bases during the Cold War, and the leaders of Russia and Belarus, along with those of Ukraine, played prominent roles in bringing about the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

In the tumultuous years that followed, Lukashenko and then Russian President Boris Yeltsin signed a series of agreements and treaties intended to integrate the two states economically, politically, and militarily. The process culminated in a 1999 treaty creating the so-called Union State of Belarus and Russia, although historians say the effort was mostly symbolic and that it became a source of bilateral tension. The governments collaborated most on integration in the military sphere while implementing little in the way of politics and economics.

More From Our Experts

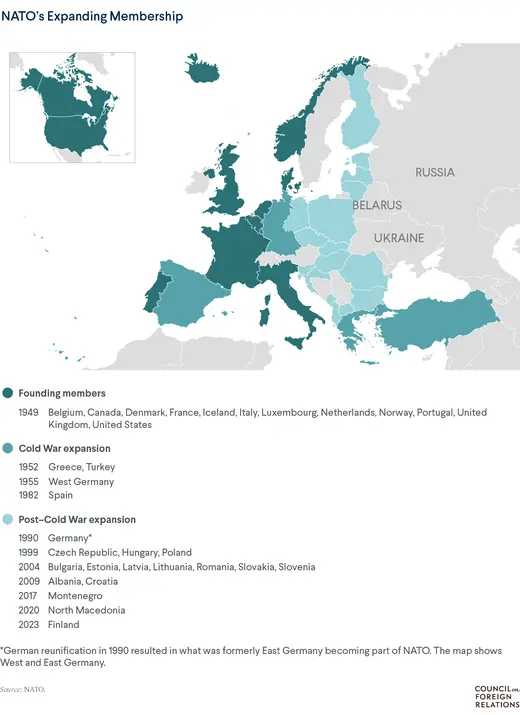

Belarus also joined Russia’s multilateral defense and economic projects: the Collective Security Treaty Organization, created in 1993, and the Eurasian Economic Community, formed in 2000. Moscow forged the organizations to consolidate its influence in the post-Soviet sphere and serve, at least nominally, as counterweights to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU).

But the two countries have also feuded over the years, particularly as Putin grew frustrated with Lukashenko’s efforts to preserve Belarus’s sovereignty and his perceived foot-dragging on integration. Strains have repeatedly surfaced over Belarus’s economic dependence on subsidized Russian energy, and over other matters, including Lukashenko’s refusal to recognize the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two Russia-controlled separatist regions of Georgia, and of Crimea, a Russia-occupied region of Ukraine. He finally recognized the latter in late 2021.

More on:

Belarus

Russia

Ukraine

Military Operations

NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization)

What role has Belarus played in the Russia-Ukraine war?

The Lukashenko regime has played a central role in Russia’s war against Ukraine. In late 2021 and early 2022, Belarus gave Russian forces a significant strategic advantage by allowing them to stage their assault on Kyiv from Belarus, which lies just eighty kilometers (fifty miles) to the north of the Ukrainian capital, in their ill-fated attempt to rapidly decapitate the Ukrainian government. An attack on Kyiv from Russia’s border with Ukraine had to cover at least twice the distance. The shorter route from Belarus also allowed part of the Russian offensive to strike Kyiv from the west, without having to cross the Dnipro River (referred to in Russian as the Dnieper River), while another prong of the invasion attacked from the east. Ukraine was able to repel the Russians from the northern part of the country despite these advantages.

In recent months, Belarus has also become a base and training ground for the Wagner Group, a Russian paramilitary organization, and reportedly a host to Russian tactical nuclear weapons. These destabilizing developments have raised tensions with neighboring Poland and the Baltic states, all NATO members and strong supporters of Ukraine.

In July 2023, Lukashenko looked to play a role in persuading Putin to allow the mutinous Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin to seek refuge in Belarus, although some analysts question the value of his contributions. “Even in his fleeting moment of glory, Mr. Lukashenko cuts a pathetic figure as a Russian pawn,” writes CFR Distinguished Fellow Thomas Graham. “Perhaps the one worthy service he has performed for his country over the years is to briefly show how Belarus could position itself as a respectable player in European affairs.”

Why did Lukashenko intensify ties with Russia in 2020?

Lukashenko initially attempted to maintain Belarus’s independence in the years following Moscow’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014. He held off on recognizing it as a Russian territory and instead tried to position Belarus as neutral ground for diplomacy between Russia, Ukraine, and west European powers. His attempts worked, at least temporarily, as Minsk became the primary venue for multiyear discussions between the parties. However, the so-called Minsk agreements they produced were never implemented.

Lukashenko was eventually forced to drop his diplomatic posturing and embrace Russia amid an extraordinary uprising in 2020 that threatened to unseat him. Deep cracks emerged in his regime after he rigged the presidential election that year and ordered a crackdown on the nationwide anti-government protests that followed the vote. With domestic pressure and international opprobrium mounting, Lukashenko turned to Moscow for political, economic, and security assurances. Putin reportedly set up a special Russian police force to come to Lukashenko’s aid if asked.

Experts say the crisis marked a major turning point in the relationship. In the months leading up to his embrace of Putin in 2020, Lukashenko continued to appear as a highly reluctant Russian ally, accusing Moscow of “blackmail,” calling talk of unification “exceedingly stupid,” and hosting high-level talks with U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton. Just weeks ahead of the election, he alleged that Putin had sent mercenaries into Belarus to sow unrest. But amid the postelection protests, Lukashenko became completely reliant on Russian support and started talking more about the two countries’ common fatherland. “This is music to the Russians’ ears,” said CFR Senior Fellow Stephen Sestanovich in 2020. “Now the Russians see in [Lukashenko’s] vulnerability an opportunity to make [the Union State] more of a reality, to absorb the institutions of the Belarus state into their own.”

What does the Belarus-Russia alliance mean for European security?

Prior to its role in the Russia-Ukraine war, Belarus served as a strategic buffer—or stabilizing force—between Russia and Central Europe, a geography that became more precarious with NATO’s post–Cold War expansion.

The Lukashenko regime’s complicity in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its widening military cooperation with Moscow will likely have enduring consequences for European security. While Belarusian troops have not joined the war—Lukashenko says they only will if Belarus is attacked—his regime continues to provide Russia with essential support as a base of operations. Thousands of Russian military members continue to train in Belarus alongside Wagner paramilitary fighters. Their ongoing presence has compelled Ukraine to boost fortifications along its 1,000-kilometer (620-mile) border with Belarus, expending resources that could otherwise be used in its counteroffensive in the east.

Meanwhile, Putin has said that Belarus is now hosting Russian nuclear weapons, and he has reemphasized the two countries’ collective defense. “Belarus is part of the Union State, and launching an aggression against Belarus would mean launching an aggression against the Russian Federation,” he said in July.

These developments have also significantly raised tensions with neighboring Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, all of which are ramping up security on their eastern borders. The three NATO and EU members also blame Lukashenko for facilitating the trafficking of thousands of migrants from the Middle East and North Africa across their borders. Some analysts have characterized the countries’ recent construction of hundreds of miles of barriers along Belarus’s western borders as a new “iron curtain” [PDF]. Leaders in Lithuania and Poland have also expressed concern that Russian forces in Kaliningrad (a Russian exclave located between the countries) and Belarus could try to seize the so-called Suwalki Gap, a ninety-six-kilometer (sixty-mile) strip of borderland, in an attempt to cut the Baltics off from their NATO allies to the south. However, some analysts say those concerns are overstated.

Despite staying out of the fighting thus far, there is a risk that Belarus becomes directly involved, which would significantly escalate the conflict. Some analysts say that Ukraine’s limited attacks on Russian soil, which have included long-range drone strikes on Russia’s capital, have increasingly unnerved Lukashenko, who fears that NATO and the exiled Belarusian opposition are attempting to use the war in Ukraine as pretext to topple his regime. He allowed Russian nukes into Belarus partly so they could become a deterrent, analysts say. Others note that Belarusians are divided in their feelings about Russia’s war and say that many soldiers would refuse to fight Ukraine if ordered.

Ukraine has stated publicly that it does not plan to attack Belarus, but it has accused Russia of plotting “false flag” operations against Belarus to lure Lukashenko into the conflict. “The problem is that by getting so closely involved with Russia, Lukashenka is blurring the line between the two countries,” writes Artyom Shraibman, a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, “and that line had previously guaranteed a more restrained Ukrainian attitude toward Belarus.”

What international pressure has Belarus faced?

The United States and European Union have applied sanctions against Belarus on and off since the early 2000s, often imposing restrictions as a punishment for Lukashenko’s suppression of democracy and human rights abuses, and then later easing them as an incentive or reward for his making certain political accommodations. For instance, Western powers suspended many sanctions in the mid-2010s amid Lukashenko’s diplomacy surrounding the Minsk talks and following his release of several political prisoners.

Prior to 2020, Belarus was still considered a relatively open, though highly centralized, middle-income economy, often noted for its tech industry. It was also participating in the EU’s Eastern Partnership and on a path to join the World Trade Organization. But Lukashenko’s recent transgressions and the resulting Western sanctions—including the severing of important trade corridors through the Baltics and the banning of flights into Belarus—have isolated the landlocked country’s market and increased its dependence on Russia. Meanwhile, thousands of valuable businesses and workers have fled Belarus.

In September 2023, EU lawmakers called on the International Criminal Court (ICC) to indict and arrest Lukashenko for war crimes he allegedly committed during the Ukraine war. The ICC indicted Putin on similar charges in July, limiting his ability to travel internationally.

Source link : https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/belarus-russia-alliance-axis-autocracy-eastern-europe

Author :

Publish date : 2023-09-27 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.